The Abuse Epidemic Hiding in Idyllic French Towns Is Flat-Out Frightening

Every three days In France, a woman is killed by her husband or ex-husband.

With more stories of female harassment and #MeToo initiatives emerging daily, International Women's Day feels even more impactful this year. Here, in collaboration with our partner CHIME FOR CHANGE, is a look at yet another atrocity that is swept under the rug: physical abuse culminating in murder.

Every three days In France, a woman is killed by her husband or ex-husband. Miscellaneous news articles are published in the media. Flashy headlines but little content as the press rarely investigates the nature of these violent acts. Over the course of almost a year, the French reporter Laurène Daycard have been looking back on the life of one of the 123 women that disappeared in 2016. By telling Géraldine Sohier’s story, killed on October 12, 2016 by her ex-husband, Laurène Daycard wanted to give a face and a voice to the many victims of femicide in France.

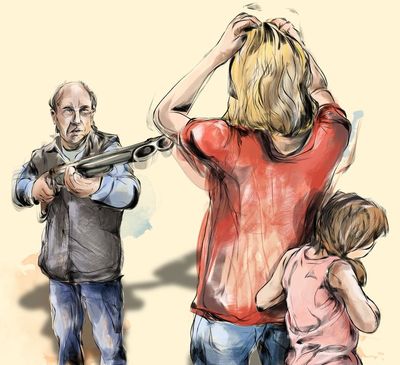

When someone dies, we like to tell stories about how wonderful a person was. In Géraldine Sohier’s case, her loved ones talk about a “bubbly, generous and funny” woman, “someone who brought joy to every occasion” and “only saw the good in people.” On October 12 at 5 pm, Géraldine's soon to be ex-husband, Éric Gallois suddenly showed up at her work place. He had a shotgun which he emptied on her. Their 10-year-old daughter was on the scene. Right before committing suicide, Gallois told the girl, “The gun is not for you, it’s only for grown-ups” while her mother was covered in blood. The little girl, now an orphan, was hospitalized for 8 days.

“My mother wasn’t happy but she always wanted to make everyone else happy."

The murder took place at the municipal library in Villers-Allerand, in the department of Marne. With its ancient stones, its bell tower and war memorial, the village is picture perfect. At the local school, there is only one class for all the children regardless of age and grades. Géraldine, a tall, blonde, 49-year-old woman, was very involved in the local community. That August, she'd taken a part-time job as a librarian. She was pleased because for years she had been going from one small job to another.

At home, she oversaw her two daughters’ educations. She also had two adult sons living on their own. Her best friend often said to her, “You will see, the day you achieve financial independence, you’ll have everything.” Until then, Éric had been the breadwinner of the family, alternating between periods of unemployment and agricultural jobs. He also owned some vineyards. Their separation began in July 2016 when Éric, known for his bad temper, threw his wife and their two children out onto the streets. The three of them only had time to grab a few things for school and some clothes before seeking refuge at Géraldine's mother Brigette's. After the couple separated, Géraldine was feeling better, finally taking some time for herself. She went to the hairdresser and started a diet. The day after the murder, the press reported on the story under the heading “In other news...”The regional paper, L’Union, titled its story “Drama in Villers-Allerand." The news agency AFP published a short article on the incident. The tone was factual and they spoke of a “family drama.”

“We will not eliminate domestic violence without helping the perpetrators.”

The story was recounted like this on various sites, including Europe1, Paris Match, and Le Parisien. And then, it just vanished. Three months after Géraldine died, at the end of January 2017, I took the bus at Reims train station to meet with Géraldine's mother at her home in Tinqueux. My own country is almost an uncharted territory for me as a reporter. I have often travelled outside of France to report on the plight of being a woman in other countries. In Albania, I met women who had been forced to have an abortion because they were pregnant with girls (it’s called selective abortion). I also went to the Middle East to find out exactly what it's like to be a woman in the Islamic State of Iraq and conducted some interviews in Turkey regarding femicide. There, I learned that assassinations of women are most common after a separation or after asking for a divorce. So when I got back home, I started to collect newspaper clippings that reported on these kinds of incidents in France and realized that sadly, it’s almost just as common in my own country. That’s how I found myself aboard that bus.

Through the window, Reims, ‘the city of kings’ as it is called, slowly revealed a landscape of grey concrete. An industrial estate, then some residential roads and low-rise buildings, the name of my stop: “Casanova.” On the phone, Brigitte became talkative as soon as we started discussing her administrative nightmare. The death of her daughter had triggered an avalanche of paperwork. She needed to become the children’s legal guardian, was appointed a public lawyer and had to make sure the girls received their life insurance money among other tasks. “I have so many papers to fill out it’s basically like writing a book” she said ironically. But she is not one to abandon the fight. Before hanging up, she gave me her email address so that I could tell her about my investigation. “Each year,” I wrote to her before we met, “statistics state the total number of women killed by their husband or ex-husband without any further details. Victims are grouped under one miserable miscellaneous headline. These women need to be given a voice and redeem their individuality.”

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Brigitte lives in a small white house in a row of identical houses and winter has covered this Reims suburb with a fine layer of frost. As she opens the door, her smile is hesitant but her pink fleece warms the atmosphere. Her granddaughters, her “little ones” as she calls them, live with her. Her husband, who was an electrician, died a few years ago from skin cancer. “His passing has shaped my character,” she tells me reservedly. Having previously worked as an auxiliary nurse in traumatology and cardiology, she is now in her seventies and lives off a small pension.

When she invites me into the warmth of her home, her granddaughters had already left for school. “Last night, the eldest dreamed that she saw her dead mother,” Brigitte told me, saddened. The girls each have a bedroom, but they can’t sleep without each other since the murder. The living room is at the end of the hallway, which is decorated with African figurines. Sitting upon the wooden sideboard is a photograph of Brigitte and her daughter, both smiling broadly and leaning on a village sign that reads “Sohier," (in Wallonia) like their surname. Next is a photograph of Brigitte and her late husband. It must have been taken in the eighties, when Géraldine was just a teenager. “She always had a huge smile on her face. But she was never happy with men. Lately, her character had changed,” Brigitte says.

One of Sohier's grandsons, Émeric, joins us. He wants to meet “the journalist.” His grandmother, who must be half his height, calls him “my ragamuffin." This 25 year-old has shaved his head, mourning the loss of his mother. He speaks with a hoarse voice.

“I spend my time shut off in my room. Sometimes, I look out the window... but I’m on the ground floor,” he says. Émeric is unemployed and lives with his partner and their baby in a working-class neighborhood. “You know, my mother wasn’t happy but she always wanted to make everyone else happy. Why would he take our mother from us? Why would he put us through that?”

Émeric never liked his stepfather – not that he calls him that. He doesn’t call him anything at all; he says “the guy” or “the other one." One night last year at dinnertime, the two men had an argument. Émeric had made the mistake of writing a text message at the dinner table. “He had a bottle in his hand, he was ready to hit me," Émeric explained, getting up quickly from his chair to re-enact the scene. “Be careful with the furniture," his grandmother rebuffs immediately.

“He was getting close to me and was really angry. I had a knife in my pocket so I stabbed him. It was instinctual, a fight or flight moment.” Émeric was given nine months in prison, during which time he turned to Catholicism. “I know that today my mum is safe where she is” he says. Brigitte interjects, “Well, she would have been even better here with us.”

Géraldine is one of the 123 women who was killed by their husband or ex-husband in 2016. The State only started to keep records for these violent deaths from 2006, from which point, at least 153 women had been killed by their partner or ex-partner. The violence that existed before the murder, and the consequential effects it has on the victims’ families is never reported. Sometimes, journalists even write about these stories in a very blasé manner. The feminist blogger, Sophie Gourion has listed them on her Tumblr account under the title “Words kill," for example, “Pissed off in Paris: Partner kills wife and throws her in the trash," could be found on Le Parisien’s website this summer. In May, the magazine 20 Minutes published a story titled, “Morbihan: Drunk Man Throws Wife Overboard.”

They invoke a “crime of passion,” as if putting a bullet in your partner’s head had anything to do with love. When I broach the subject with my various relatives and friends, they often respond with, “men get killed as well.” And they do. In 2016, 34 men were killed by their partner or ex-partner — one every 10 days. Among the 28 men killed by their official partner (wife, civilly partnered), at least 60% of the victims were themselves violent, which leads us back to question the roots of male violence.

People also say: “Laurène, this ain’t Bagdad!” But, considering it’s always worse elsewhere is a cowardly way out. Each year in Simone de Beauvoir’s country, 218,000 women are victims of sexual and/or physical violence from their (ex-) partner.

Only 14% of victims press charges. More than finding themselves alone on the street at night, it’s the intimacy these women share with their partners which makes them vulnerable to psychological and physical violence. And it gets worse when they are financially dependent: On average, French men receive a salary that is 18.5% higher than their female counterparts, according to the National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (Insee).

For now, according to Article 222-4 of the Penal Code, a murder charge is extended to life imprisonment when the perpetrator is the spouse, partner or ex-spouse. This is the penalty faced by Mamadi Camara, who killed his ex-partner Maryline Blondeau, another of the 2016 victims whose family I interviewed.

The murder took place on July 23, 2016 in Carmaux, in the department of Tarn. Mamadi Camara is currently in prison, awaiting a trial that will take place at some point in 2018. Maryline was a baker in this village of 10,000 inhabitants, an old mining town on the outskirts of Albi. Having recently separated from the father of her two children, Maryline, a tall, athletic blonde started going out with Mamadi, a 51-year-old laborer. The two were very much in love. Until the first blow. It was the evening of Maryline’s birthday and as they were leaving a restaurant, the mother of two started talking to another man. Mamadi couldn’t stand it. On the ride home, he became aggressive. She swiftly broke up with him but one morning Mamadi stabbed her, behind the bakery.

Afterwards, Thierry Kowalski, her ex-husband and the father of her two children, tried his best to keep a level head. He is a very sweet, reserved man. His house is built right next to the railway line. He lived there before with Maryline and his family. Little by little, their love began to dissolve into routine and they made a mutual decision to separate.

When Thierry found out that she had been getting close to Mamadi, he was wary. Not because he was jealous or because he had suspected this man was capable of such a crime, but because, “she trusted people too much and didn’t think about how they would abuse that.” Shortly before her death, Maryline had begun to seek contact with the father of her children. “I would see her more and more when I was jogging around the village” he reflects. Before dropping me off at the train station, Thierry makes a detour through the cemetery. The low afternoon sun warms the gravestones. He silently makes the sign of the cross, before whispering, “what a waste.”

With Géraldine, it was more difficult to retrace the history of violence. Since the murderer had committed suicide, there was no trial, and many aspects of their relationship remain undisclosed. In her police statement, her eldest daughter, born from a previous marriage, said that she had been witness to scenes of domestic violence. Brigitte, Géraldine’s mother, knew nothing about it. “I read it whilst I signed her statement. Maybe my daughter didn’t tell me anything to protect me.” On July 20th, just a few days after taking refuge at her mother's in Tinqueux, Géraldine had gone to the courthouse in Reims to meet a women’s association specialized in legal advice. “She was afraid,” recalls Nadège Bezard, the employee who received Géraldine. “I explained how someone would go about pressing charges.” They suggested that she request a ‘remote-protection’ device from the prosecutor available to victims of rape or domestic violence.

This portable device would allow her to call a dedicated helpline at any moment. Géraldine had refused, thinking it wouldn’t do any good. Her best friend, Corinne Venturi, knew Géraldine was unhappy in her marriage, but she never heard her complain about threats or violence. The two women met in the eighties when they were both working at the Hector sausage factory. Corinne was 27 years old, and Gégé, as she called her then, was 19.

In the evening when they clocked off, they always left together. It was the era of the pop singer Étienne Daho and The Communards’ songs were all the rage. “Her parents called her ‘the gust of wind!' She came in to take a shower at dawn before heading back out again to work," Corinne tells me, smiling over her espresso at the Buffalo Grill in Tinqueux. When Éric came into Geraldine’s life, Corinne had to take it upon herself to not lose her best friend. “Sometimes I would say to myself, damn it, what is she doing with this guy?” she said, irritated. The Géraldine she knew when she was younger “wasn’t the type of girl who let people push her around. She always knew how to stand up for herself.” As she drives me back to the station, Corinne is still contemplative. At a red light she turns to me, although it seems like she is talking to herself. “Thinking back, perhaps we should have said something to Géraldine, “For God’s sake, what are you doing with him?” But did we even have the right to do that?”

I have often asked myself that same question. At school, in the small village by the sea where I grew up at the beginning of the millennium, we thought that feminist struggles were things of the past, that we had achieved equality. But when I was studying Political Science, one of my classmates was going out with a guy with a bad temper. She sometimes told me about his jealous spells, when he would insult her and call her a bitch. One day, he even broke his wrist by punching a wall.

Another of my friends – let’s call her Léa — was severely hit by her boyfriend. Both of them were studying in the same business school. To pay for her studies, Léa worked all summer as a waitress in a beach bar, from our home region. One evening, her partner picked her up from work. He was drunk and angry. He punched her many times and made her fall out of the car. “As an apology, he offered me a luxury hand bag a few days after," recalls my friend. She never reported it to the police.

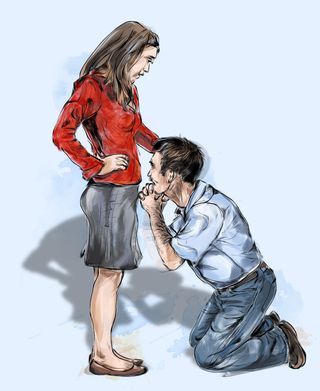

Isabelle Steyer is a criminal lawyer and has studied this question at length. She has been defending victims of domestic violence for more than 20 years. She sent an accused husband directly to prison with one of her first defense speeches. However, the wife came back time and time again to demand his release. “Not because she was afraid, but because he was sending her letters of apology, saying that this time he understood he was in the wrong. That he was the best husband in the world.” It was her who helped me realize that it’s all about control.” This form of psychological imprisonment causes the victim to downplay their sufferings and give excuses to their perpetrators which makes it even more difficult for her family to notice the danger” Isabelle explains.

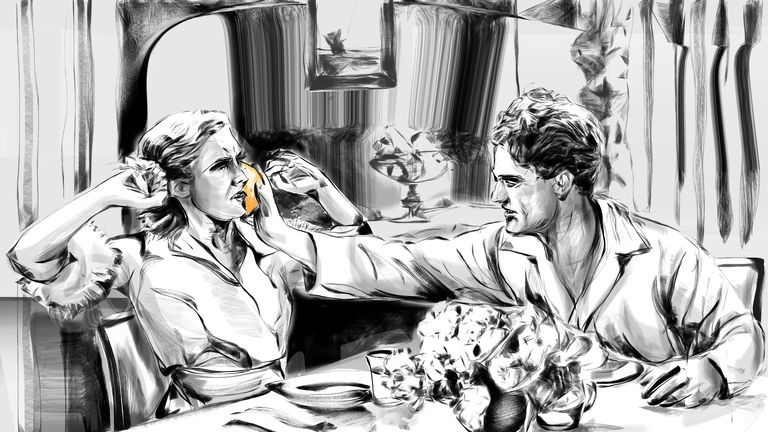

“Violence happens in stages. One day, the husband is going to be verbally, and maybe even physically abusive. The most ordinary detail can trigger fury. The meal is rubbish; the house isn’t clean enough or the table isn’t set properly. The complaints escalate over the course of an hour, two hours, sometimes a few days. When the perpetrator realizes that his wife cannot take it anymore, he gets down on all fours and tells her that he cannot live without her, that she is the mother of his children. In short, the opposite of everything he said before. Isabelle Steyer interprets this as the honeymoon phase. By blowing hot and cold over a fragile person, you make them think that they are the problem.

During our interview at the Buffalo Grill restaurant, Corinne had mentioned something along the same lines: “Éric would buy her amazing presents, like a state-of-the-art treadmill.”

According to Brigitte, her daughter had made the decision to end the relationship when a fine came through the mail because her husband had forgotten to confirm his address at the Police Station. She had no idea that Éric had been given a suspended 3 month prison sentence in 2004 by Reims Court for sexual aggression towards a vulnerable person. This fact was not mentioned in the news after Géraldine Sohier’s death either. In this previous case, the proceedings had initially been opened as a rape allegation before being reclassified as attempted murder charges. A journalist from the newspaper L’Union had covered the proceedings. He wrote that Éric Gallois had joined the victim in their bed and wanted to have sex, she had skin cancer and was exhausted. In his article, he wrote, “She refused. He insisted, grabbed her, harassed her, tried to abuse her,” and it goes on. The victim ended up with bruises on her legs, her thighs, her wrists and her shoulder. Per the report, Éric had denied everything and stated that she “had hurt herself by falling down the stairs.”

In the L’Union archives, I found other press cuttings that relate to Éric Gallois. One of them is from 2007 and reports a violent altercation with a winemaker from the Marne. A different article highlights a letter Éric Gallois sent to a magistrate in January 2010: “You are all pigs and Mafiosi who act out of spite and for money,” he wrote, according to the local paper. By all accounts, Éric Gallois was a difficult person, “a violent man.” But does that make him a monster?

On August 4, 2014, France introduced awareness courses that were finally directed toward offenders of domestic and sexist violence. Up until then, such courses were only available for perpetrators of violence against children, infractions of the Highway Code, or drug abuse. It is the participants’ responsibility to attend and they generally last one or two days. It’s a small step in the right direction inspired by the recommendations of psychologist Alain Legrand. Legrand is the President of the National Federation for Associations and Centers for Apprehension of Perpetrators of Domestic and Family Violence. He believes that a long-term treatment needs two or three years of monitoring on average, with at least one meeting a week. “We will not eliminate domestic violence without helping the perpetrators,” the practitioner insists. He monitors around 150 people annually from his apartment in Paris where he holds his consultations. Of this group, 2% to 3% are women. “I do not work on violence itself, but on what causes violence,” he explains. Because for these violent men, there’s always a legitimization. 'She’s the one who provokes me by saying things, by not doing what I ask' they’ll say. The majority have very low self-esteem. The doorbell rings. A new patient arrives. The session costs 25 euros, a much lower price that the market average. “The Office for Women’s Rights has just reduced our grant because their budget is stretched too far,” he says regretfully. “I keep my own fees down so we can keep running.”

At the beginning of October 2017, I go back to Tinqueux. On my way to the bus I stop at a florist. I know that the following week will be one year since Géraldine’s murder. The vendor assures me that the flowers will last. He calls them “eternal." Brigitte accepts them with pleasure. She sits over a coffee around a large wooden table covered with a Christmas tablecloth. She is pleased to have finally achieved legal guardianship of her youngest granddaughter, who has just started school and is still being monitored by a psychologist. “She seems to be doing well," her grandmother reassures me. The eldest is now in her first year of Sixth Form and wants to be a lawyer. “She has good grades but a teacher has told her that he doesn’t like her. They are difficult sometimes. I’ve told her not to pay any attention to him — she should work hard for herself.” Since coming back from their holidays, the girls have managed to sleep in their respective bedrooms. “They might still have nightmares, but they don’t mention them to me anymore.” Brigitte’s voice trembles. “Do you have any more questions? It’s all a bit emotional. I try to be strong, but occasionally I break down as well...”

Walking back to the Casanova bus stop, my legs are shaking and I can still sense Brigitte’s pain, so palpable in her trembling voice. I think about Géraldine, Maryline, and all the others. I wish I didn’t have to write this article.