In Afghanistan, members of a secret organization of women risk death to give other women education and hope. Eve Ensler took a harrowing undercover journey to chronicle their fight against the Taliban -- one of the most repressive regimes in history.

The Taliban Forbids Women to:

If a woman breaks these laws, she risks being flogged or killed.

Documenting the Situation

Freshta is 26, thin, pale and haunted. She is an undercover reporter who travels across Afghanistan and risks her life to document the atrocities of the Taliban, the fundamentalist Muslim regime that controls her home country.

"On Fridays," Freshta says, "the Taliban closes the shops and streets in Kabul and forces all the people, children included, into a stadium. They are forced to watch as thieves have their hands cut off and are hung from trees. Yet the Taliban is what has made these people so poor they must steal. I have seen women stoned to death in the stadium for refusing arranged marriages. And the Taliban actually sells popcorn before these events -- executions have become entertainment for children."

She reports on other atrocities: A 6-year-old girl was beaten for carrying schoolbooks in public. Two cousins, a boy and a girl, were buried alive for talking in the bazaar. Commanders abduct and rape girls. "The girls don't want to be interviewed," Freshta says, "because they are ashamed. I interview their mothers, who usually say, 'Our daughters are dead to us.'"

Freshta tells me that since she became a reporter, she faints all the time. But she will continue "as long as I have the ability to publicize the shocking situation of my people. I hope I will live to see the elimination of these criminals."

Stay In The Know

Marie Claire email subscribers get intel on fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more. Sign up here.

RAWA Takes Action

Freshta reports for the newsletter and Website of RAWA, the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan. More than 2,000 members of this clandestine network provide shelter, education and medical services to Afghan women and girls -- all in defiance of the Taliban. Unable to show their faces in their own country, they are building international connections through their Website. I first contact them by email.

After putting me through a series of security checks, RAWA's leaders agree to show me their schools and orphanages -- and to help me secure passage into Afghanistan to witness life under the Taliban firsthand. I am traveling with Willa Shalit, the executive director of V-Day, a global movement to end violence against women, and we start our journey in Pakistan, home to 1.2 million refugees who have fled the Taliban.

In a city I agree not to name, a driver sympathetic to RAWA's mission takes us down narrow, garbage-strewn streets until we reach an unmarked house. Behind a gate, unseen from the street, a guard armed with a machine gun stands watch. He lets us inside, where we find clean, ordered classrooms decorated with brightly colored pillows.

What We Learn

RAWA operates a dozen schools like this one in Pakistan, some in desert refugee camps and others in RAWA members' own houses. In Afghanistan itself, RAWA runs 65 schools and 33 orphanages, all housed secretly in private homes. The Pakistani schools face harassment and raids by Taliban sympathizers, but in Afghanistan, both students and teachers risk death. RAWA rotates school locations and strictly limits class sizes to avoid detection.

The women studying at the school I visit, refugees of every age, tell me their stories in turn. "A member of the Taliban struck me with a stick because I wasn't wearing a burqa," says a manic, 48-year-old widow, referring to the long Afghan garment that provides only a small grill for air and sight. "I fell facedown on a stone. No operation will fix it." She shows me her knee, swollen and deformed.

Then Freshta speaks. Afterward, a woman says, "We want to show you something. One RAWA member smuggled a camera in under her veil and filmed this." She brings out a television and VCR and puts in a videotape.

On the screen, we see images from Freshta's horrifying account of the stadium executions. About nine Taliban men arrive at the stadium in the back of a Toyota pickup truck. Soon, another truck appears carrying three women covered in burqas. A man with a microphone reads from the Koran.

One of the women is led into the center of the stadium and thrown to the ground. A Taliban man places his gun to her head, and without pause, fires it. Wails and cries come up from the crowd, but the dead woman is left on the ground like garbage. Someone turns off the TV.

A Martyred Leader RAWA's founder, a poet and activist named Meena Keshwar Kamal, was 20 years old when she formed the group in 1977 in hopes of gaining equal rights for Afghan women. At the time, this cause was not yet life-or-death: Women were earning Ph.D.'s and working as doctors, lawyers, and teachers. If they wore the burqa, it was out of religious preference, not in obedience to national law.

But in 1979, Soviet troops invaded the country to back the communist government then in power, and Islamic and tribal groups known as jihadi mounted armed opposition. RAWA staged public protests opposing the communists and the jihadi with equal passion, and Meena paid for it with her life. In 1987, she was killed in her home in Quetta, Pakistan, by the Afghan KGB and their fundamentalist accomplices. After her death, RAWA members went underground, determined to complete what their leader had begun.

Since Meena's assassination, RAWA has had no single leader -- that would leave them too vulnerable. Instead, the group is directed by a rotating council of 12 women. (Men support, protect, love and marry RAWA members, but they cannot join.) Watched over by bodyguards, the council meets every three months, both in and outside of Afghanistan. At the end of each meeting, members decide where they will next convene. They tell no one else of their plans.

A Dangerous Mission

In Pakistan, we meet journalists who have been waiting many months to get into Afghanistan. But we are very lucky. Within a week, after an extraordinary intervention on our behalf by the International Rescue Committee, we secure the visas we need. We will be escorted by Uma, a sweet 20-year-old woman who has been on only one other mission for RAWA in Afghanistan. If questioned, we agree to say that we are tourists and Uma is our translator. Uma is required to don the suffocating burqa. Willa and I, as foreigners, are permitted to cover ourselves with scarves instead. Notebooks, cameras and cell phones are banned, but we bring the first two anyway. An armed Pakistani policeman travels with us; when checkpoint officials along the route through the Himalayas seem ready to turn us away, he waves his Russian-made machine gun and they let us pass.

At the border, however, Taliban guards force us out of our car, claiming we do not have the right permit for it. Abandoning the car, we actually walk across the border into Afghanistan, our luggage in tow.

We hire a new driver, who loads us into a decrepit station wagon and takes us far through the desert to a particular city, where we check into a hotel. Like all public lodgings, it is run by the Taliban -- and judging from the urinal in our bathroom, we may be the first women to stay here.

Uma has set up a covert RAWA meeting for that evening. We cover ourselves in burqas in an attempt to blend in and avoid being followed. The three of us, covered in miles of fabric, squeeze into a tiny cab, a glorified golf cart. Almost immediately, the heat becomes unbearable, and I gasp for breath. I'm trying to be brave, but it's useless. I wouldn't last a day under the Taliban.

We take a circuitous route to a RAWA school, a house indistinguishable from the impoverished dwellings that surround it. A young teacher tells me that 35 small classes are held here, teaching science, math and reading. The literacy rate among women in Afghanistan is now 4 percent, she tells me; without education, there is no hope of raising a generation strong enough to defy the Taliban.

"The students arrive at different times, one by one," says the teacher. "If someone knocks on the door, we hide the blackboard. The students have so much interest in school. Most don't know it's RAWA -- but they know that if the Taliban sees them learning, they could die."

I interview the women and write for a few hours in a room illuminated by only a little pocket flashlight -- the Taliban has cut off the city's electricity. Then they tell us we must go: If we are seen outside after the 9pm curfew, there will be trouble. The women hug and kiss us again and again. They plead with us to tell their stories to the world, but they have no self-pity.

Staring Down the Taliban

We spend a week in Afghanistan, with only one joyous moment. I had heard that the Taliban beats women who eat ice cream in public. For some reason, this haunts me. So when Uma tells us she knows a secret place where women go for ice cream, I can't wait.

We walk through a crowded bazaar and into a broken-down restaurant. In the back, sheets have been hung from the ceiling to create a makeshift room. Willa, Uma and I walk in and sit down, and the sheets are pulled around us.

When Uma lifts her burqa and eats the cool, sweet ice cream, she becomes a child -- in the time before women were locked away without schools or jobs, when they could laugh and see the sky. For a moment, no one has control over her. Then we are warned that Taliban men are circling the bazaar in their pickups. The moment is over.

Some part of me fears I will never get out of Afghanistan. And indeed, as we drive back to Pakistan a few days later, our car gets stopped by a member of the dreaded Department for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice (DPVPV). He is huge and raging, a mass of long hair and dirty beard. He sees that I am covered but not wearing a burqa, and he orders me out of the car. He is clutching a wooden paddle, attached to which is a long, flat, wide leather whip used for flogging. I recall the black and blue ankles of the woman I met at that first RAWA school, and the way she still had trouble walking.

I stare at him. He stares at me. Suddenly, our driver leaps out of the car, hysterical, giving Mr. Taliban all kinds of visas and explanations. As a result, he lets us go.

One minute out of his sight, our driver begins laughing wildly, as one might after a near-death experience. Uma confesses that it was the first time she had seen a member of the DPVPV in the flesh -- it made the struggle real for her. But Willa is quiet, very quiet. She keeps the cloth on her face for quite some time, even after we walk back over the border into Pakistan.

What You Can Do

For information on how you can help RAWA's cause, visit www.rawa.org.

-

Bitten Lips Took Center Stage at Dior Fall 2024 Show

Bitten Lips Took Center Stage at Dior Fall 2024 ShowModels at the Dior Fall 2024 show paired bitten lips with bare skin, a beauty trend that will take precedence this season.

By Deena Campbell Published

-

30 Spring Items That Solve My Expensive-Taste-on-a-Humble-Budget Dilemma

30 Spring Items That Solve My Expensive-Taste-on-a-Humble-Budget DilemmaSee every under-$300 spring item on my wish list.

By Natalie Gray Herder Published

-

Your Makeup Won't Budge With These Setting Sprays

Your Makeup Won't Budge With These Setting SpraysPrepare for 12-hour wear.

By Sophia Vilensky Published

-

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.

Sex Trafficking Victims Are Being Punished. A New Law Could Change That.Victims of sexual abuse are quietly criminalized. Sara's Law protects kids that fight back.

By Dr. Devin J. Buckley and Erin Regan Published

-

Her Love of Basketball Left Her Stateless

Her Love of Basketball Left Her StatelessOne athlete’s quest for freedom from Afghanistan, where the Taliban's restrictive and regressive policies on women's sports put her life in danger.

By Abigail Pesta Published

-

Sorry, Melania: It Takes More Than Fashion to Emulate Jackie Kennedy

Sorry, Melania: It Takes More Than Fashion to Emulate Jackie KennedyThe Trump administration continues to push the comparisons between Jackie O and FLOTUS, but iconic first ladies are more than their outfits.

By Jennifer Stavros Published

-

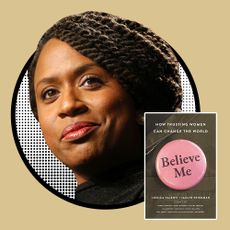

Rep. Ayanna Pressley Wants Justice for Every Sexual Assault Survivor

Rep. Ayanna Pressley Wants Justice for Every Sexual Assault SurvivorThe congresswoman speaks truth to power in Jessica Valenti and Jaclyn Friedman's upcoming anthology, Believe Me.

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

Why Many Congresswomen Wore White at Today's Swearing In Ceremony

Why Many Congresswomen Wore White at Today's Swearing In CeremonyThe fashion choice has a historic significance.

By Amanda Mitchell Published

-

RBG Wore a Collar Gifted to Her by a Fan in Her New Supreme Court Portrait

RBG Wore a Collar Gifted to Her by a Fan in Her New Supreme Court PortraitRuth Bader Ginsburg wore a collar necklace given to her by a fan in her most recent Supreme Court portrait. The Stella & Dot necklace costs $198 and is still available in gold.

By Kayleigh Roberts Published

-

I Don’t NOT Want This Ruth Bader Ginsburg-Themed Bra?

I Don’t NOT Want This Ruth Bader Ginsburg-Themed Bra?Maybe it's a lesson that we should all keep our political leanings close to our chests.

By Cady Drell Published

-

Huma Abedin Attended a Christina Aguilera Concert Wearing a 'November Is Coming' Sweater

Huma Abedin Attended a Christina Aguilera Concert Wearing a 'November Is Coming' SweaterOh, and Hillary Clinton was there, too.

By Jenny Hollander Published