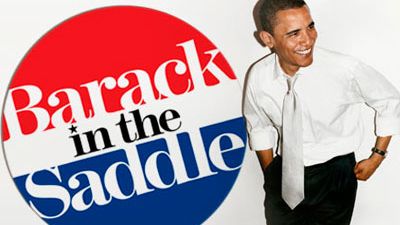

Barack in the Saddle

You know how he feels about Iraq, health care, and the economy. But where does he stand on Miley Cyrus? A candid interview with Barack Obama about women -- what we face, what we need, and what it's like to be married to an outspoken alpha.

LIVE FROM THE INAUGURATION: GET AN UPDATE FROM OUR EDITORS IN WASHINGTON, D.C.

Sitting in a classroom amid the peppy trappings of school — sports trophies, pennants, and posters (GO, RAMS!) — Barack Obama, in a sharp dark suit and red tie, cuts an absurdly chic figure. It's mid-July in Fairfax, VA, where Obama has just run a partisan-rich town hall meeting in the gym of the Robinson Secondary School. The focus was the economic empowerment of women: "We take it for granted that women are the backbone of our families," Obama told the crowd of nearly 3000, "but we all too often ignore the fact that women are also the backbone of our middle class."

As the grandson, son, and husband of alpha females, Obama appreciates women's issues. But with his campaign entering its final months, and the fervid Hillary faithful poised to make the difference in November, those issues have taken on new significance. It was in this spirit, then, that Senator Obama — a touch weary, but smooth and genial — submitted to the estrogen treatment from Marie Claire.

MC: We live in the era of Jamie Lynn Spears getting pregnant at 16, of teenage girls making "pregnancy pacts" — how concerned are you about the culture your daughters are growing up in?

BO: Michelle and I are constantly monitoring what our daughters absorb from the culture. And I don't think we're alone in feeling that the way the culture sexualizes young girls is a problem — that it encroaches on their childhood. Now, Michelle and I aren't prudes, and Michelle has frank conversations with the girls. Malia will be going into puberty soon, so we want them to be well-informed.

MC: So the birds-and-the-bees conversation has already happened.

BO: Well, more or less. But the point is we want them to grow up with a strong sense of self. We want them to feel that they're being judged on their smarts and their competitiveness and their compassion, and not just, you know, looking cute. So, we talk a lot to them about what values they should be internalizing. Michelle and I agree that our job as parents is really to allow them to make good choices.

MC: Is it working?

BO: I think we've done a pretty good job. Malia and Sasha are very down on Britney Spears and Paris Hilton. Malia is the first one to change [the channel] if something suddenly comes on that she thinks is inappropriate. If a song comes on the radio that she doesn't think is sensible, she will change it. On the other hand, she's a big fan of Hannah Montana. And when Miley Cyrus had that picture in Vanity Fair [holding a sheet to her chest], she just offered this very sensible opinion. She said, "Well, she seems like a good person. Her family seems to love her. Everybody makes mistakes, so I hope that people won't judge her for just this one picture."

MC: Is there anything you don't let them look at?

BO: We don't let them use the Internet without one of us being there. We want to make sure that they're not landing on some site that would make us blanch.

Stay In The Know

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

MC: What's it like living in a house full of females?

BO: It's wonderful, but I end up being the butt of a lot of jokes. You know, "Daddy's leaving his big shoes in the middle of the floor." "Daddy's hanging his pants on the doorknob again." "Daddy only has three pairs of shoes, and they're really old."

MC: When Michelle becomes first lady, how will she transition to the ultimate wifely role?

BO: Michelle's very comfortable in her own skin. And I like that skin, of course. So I don't want her changing, and I don't think she's looking to change. Michelle's not somebody who wants to be deeply involved in policy development. She's my closest friend and my most important adviser. But I don't anticipate her sitting around the table trying to figure out tax policy. She'll probably choose a project that she cares about. But her number-one priority is going to be these kids, and making sure that their transition is one in which the wonderful normalcy that they have is maintained.

MC: Do you think she's misunderstood?

BO: Not by people who've been paying attention. I think that if you've been watching Fox News then probably she's misunderstood, because I do think there's been a fairly systematic attempt by the conservative press to paint her in a completely false way. They latched onto the one gaffe or statement she made about being proud of her country for the first time, which, as Laura Bush acknowledged, was not something that Michelle had meant — that she had not been proud of her country before. And her very legitimate criticisms of how families are being treated and the difficulty for so many women of balancing family and work was painted as her being this caricature of an angry person. Anybody who knows her well knows she's got the best sense of humor of anyone you'd ever want to meet. She's the most quintessentially American person I know.

MC: How so?

BO: She grew up in an Ozzie and Harriet household, with mom, dad, brother, dog — I don't know about the dog, but... [laughs]. Her dad worked all his life, despite having multiple sclerosis. Mom stayed at home. They loved each other and spent their time talking and supporting each other. Michelle went to public schools; her favorite show is The Dick Van Dyke Show; her favorite food is french fries; she shops at Target. She's just a wonderfully normal, levelheaded person. Any American woman who meets her would immediately identify her as a fellow traveler.

MC: Do you think she had to wrestle with setting aside her own career to run with you?

BO: I think Michelle is like a lot of women of her generation in that she has carried within herself two very powerful ideas: one, that she's as smart as any man and can be as successful as any man in whatever she chooses. On the other hand, she loves being a mother. I'm not sure that the tension she felt, particularly when the girls were younger, had only to do with the fact that I was in politics or I was away. I think it is something that women generally are struggling with, probably because we have a society that doesn't really provide a lot of support for women in those roles. We don't provide the kind of maternity and paternity leave that other countries do. Our child-care system is a patchwork, particularly if you don't have a lot of income. It's a difficult balance, and I don't think it's one that can be entirely solved by government. But certainly we can help put women in a better position to make the decision that's right for them.

MC: You've expressed concerns about your own failings as a husband and a father, particularly with being absent a lot and Michelle being angry about it. What are some of the accommodations you have made?

BO: One of the most important things was just her feeling like she was getting heard. I know that sounds a little cheap. But I think a lot of times women feel frustrated because men are just oblivious to the issue: "The kids are fine, happy and healthy, we got a nice house, why are you complaining?" And I think that when I let her know that I understood and heard what she was saying, I think that was important to her. And I'll be honest with you — some of it was just, financially, we became less stretched. My books did well. As a consequence of my books doing well, suddenly it's easier to get takeout whenever we feel like it. It's easier to get a housekeeper to come in one or two days to help do the laundry or help clean up. It's easier to do a lot of things that, frankly, the vast majority of American women can't afford. But we're not that far removed from the situation where this work was falling on her in a very heavy way.

MC: Before your books took off, you had a period where she was earning more than you were. How did that affect your relationship?

BO: That wasn't much of an issue, because the truth is, for 11 out of the 13 years we were married, I was making substantially more than her, and during the two years that I wasn't, I was running for the United States Senate, which had its own gratifications. So it wasn't as if I felt inadequate. I've got to say, I always found it great if she was making all kinds of money. I didn't feel threatened by that at all. My grandmother generally earned more than my grandfather when I was in high school, so that probably makes me more comfortable with some of these issues than others would be.

MC: You were at a fundraising breakfast with Hillary Clinton this morning. During one of the debates, you famously described her as being "likable enough." Is she more likable now?

BO: That's an example of where you say something awkwardly and it gets pounced on. Somebody says, "You've got a likability problem," and the point I was trying to make was, I think that's silly. Hillary Clinton is perfectly likable. But I was writing notes, I didn't smile as much as I needed to, I said it, and suddenly everybody says, "Ah, that's so patronizing!" Hillary Clinton is not only likable, but she's extraordinarily capable and smart and effective as an advocate. I think she and I are going to be working very well together and hopefully for years to come to try to change this country the way it needs to be changed.

MC: Will she be in your cabinet?

BO: I'm not going to speculate at this point. But what I know is that she'll be at the center of the Democratic Party for a very long time.

MC: When you become president, how will you handle having to negotiate with countries that are committing human-rights violations against women?

BO: I believe there's a spectrum. In a place like Darfur, rape is used as a military weapon — there are no excuses, and you simply don't abide them. You mobilize the international community to change behavior in those countries. When it comes to countries like Saudi Arabia or Pakistan or others in the Middle East where women are still in second-class positions, it is important for us to recognize that the culture is not going to transform overnight. But we won't be bashful about speaking out on these issues and affirming a core belief in the equality of women. My mother specialized in international development. And her focus was on helping women get a foothold in the economy, microfinancing — helping them buy a loom or a sewing machine, or some cows so that they could then sell the milk. She was very clear that the best indicator of how a country is going to develop is how it treats its women and whether it educates its girls. And so, part of the argument we want to make is not just based on our values and our ideals, but also on practicality — letting countries know you're not going to develop as quickly if you've got one hand tied behind your back. You're not going to do as well economically if all this enormous talent represented in your female population is undereducated and not given the same opportunities as men.

MC: Discussing the importance of reading to kids, you said in the town meeting that you've read the Harry Potter books to your daughters. Who's your favorite character?

BO: All the characters were wonderful...Dumbledore's a very cool guy.

MC: Well, he's gay, apparently.

BO: [laughs] No comment on that.

MC: So, Rolling Stones or Beatles?

BO: Rolling Stones.

MC: Iron Man or Batman?

BO: Batman.

MC: If your mom were still alive, what would she think of all this?

BO: She would be bursting with pride. I don't think so much about me as about her grandchildren — our daughters and my niece. For her to see these three beautiful, graceful, highly opinionated girls, that would bring her great joy.

See the Presidential Election Guide

-

An Inside Look at 'Marie Claire’s Power Moms Event

An Inside Look at 'Marie Claire’s Power Moms EventThe celebratory soirée was one to remember.

-

Princess Sofia Missed a Dazzling Tiara Moment After Debuting Baby Princess Ines at Royal Event

Princess Sofia Missed a Dazzling Tiara Moment After Debuting Baby Princess Ines at Royal EventThe Swedish royal family brought out their best jewels for a special state banquet.

-

Simple, Effective, and Chic: 5 Outfits Our Editor Has on Rotation This Summer

Simple, Effective, and Chic: 5 Outfits Our Editor Has on Rotation This SummerAll from Nordstrom.

-

The Historic Election Victories Worth Celebrating

The Historic Election Victories Worth CelebratingIncluding momentous firsts, abortion protections, and New York's "Equal Rights Amendment."

-

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to Men

36 Ways Women Still Aren't Equal to MenFeatures It's just one of the many ways women still aren't equal to men.

-

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If Reelected

How New York's First Female Governor Plans to Fight for Women If ReelectedKathy Hochul twice came to power because men resigned amid sexual harassment scandals. Here, how she's leading differently.

-

5 Practical Things You Can Do to Protect Democracy

5 Practical Things You Can Do to Protect DemocracyHow To Advice from top celebrities and Michelle Obama herself.

-

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So Critical

Why the 2022 Midterm Elections Are So CriticalAs we blaze through a highly charged midterm election season, Swing Left Executive Director Yasmin Radjy highlights rising stars who are fighting for women’s rights.

-

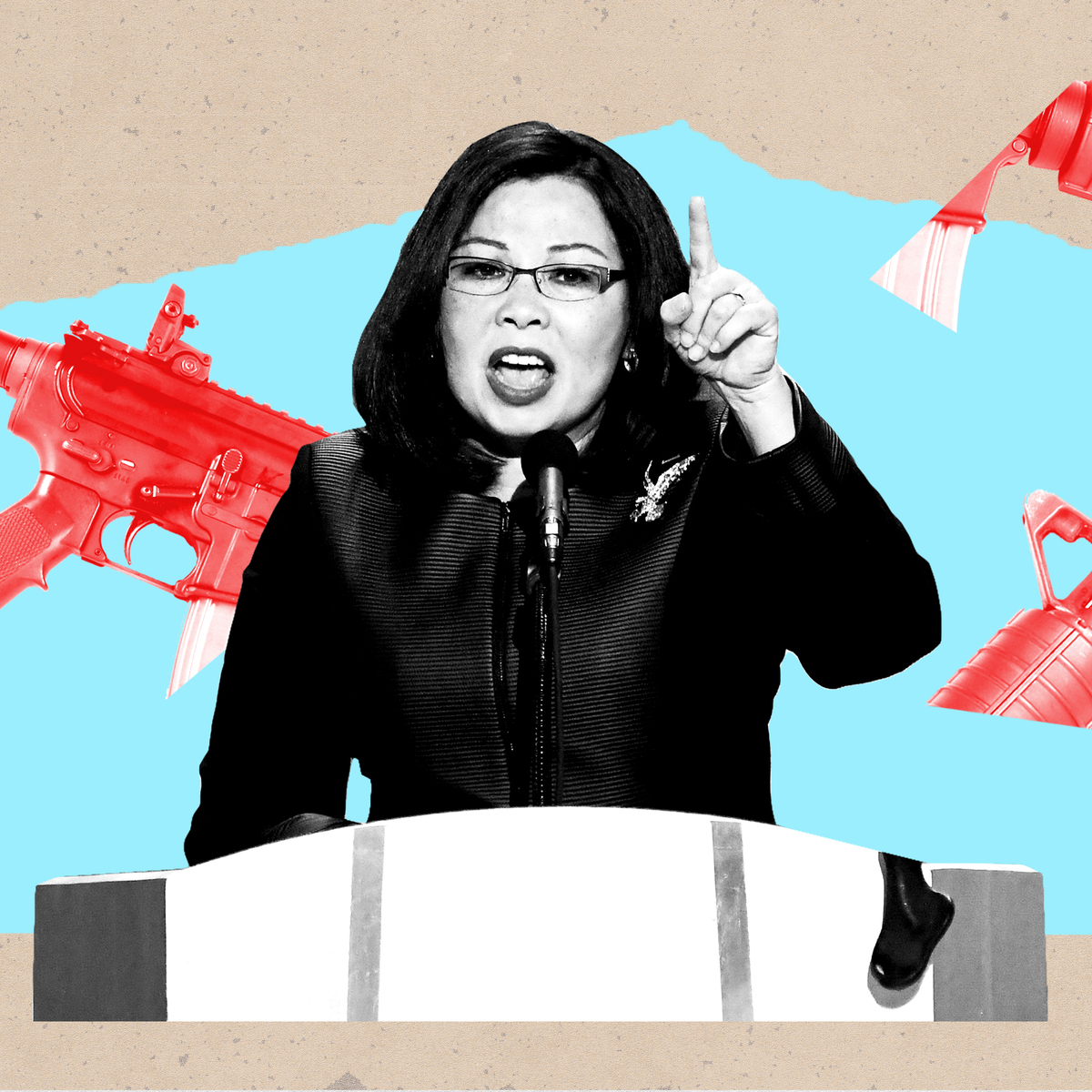

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun Safety

Tammy Duckworth: 'I’m Mad as Hell' About the Lack of Federal Action on Gun SafetyThe Illinois Senator won't let the memory of the Highland Park shooting just fade away.

-

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.

Roe Is Gone. We Have to Keep Fighting.How To Democracy always offers a path forward even when we feel thrust into the past.

-

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to Know

The Supreme Court's Mississippi Abortion Rights Case: What to KnowThe case could threaten Roe v. Wade.