What You'll Never Understand About Being Biracial

Mixed-race women on what it's like to feel black but look white.

Black people don’t have freckles.”

Those were the words that reverberated through Samantha Ferguson’s middle school–aged head after telling a boy at school that she was half-black and half-white. Classmates, confused by her appearance, had been hounding her with questions like, “What are you?”

“It really upset me. I’m a human being,” recalls Ferguson, now 24, a third-grade teacher in Glen Burnie, Maryland. “I wanted to ask them, ‘What are you?’”

Before middle school, Ferguson didn’t think she was different from other children. But, she says, the students at her predominately-white school, “dressed a certain way, looked a certain way, their hair was straight. My skin is not dark, but it’s a different tone, which made me stand out.”

Like all middle-schoolers Ferguson had crushes and wanted to be popular. “I could never be popular, though, because I didn’t look like everyone else. Boys didn’t have crushes on me because my hair was frizzy and I had freckles.”

It was the first time she realized that people are different colors—and receive different treatment because of that. “I didn’t know if I should tell my classmates I’m white, or if I should tell them that I’m black.” She didn’t know where she fit in. She didn’t know how to identify herself.

“Identity is understanding who we are in the world,” says Kerry Ann Rockquemore, co-author of Beyond Black: Biracial Identity in America. “Part of that is how others understand us, and the other part is how we understand ourselves.”

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

For many biracial people, that understanding can be both elusive and arbitrary. From checking boxes on forms to fulfilling quotas, race is used to define and control so many aspects of everyday life. And biracial people are constantly faced with a choice.

It was the first time she realized that people are different colors—and receive different treatment because of that.

Biracial women who struggle with their own identity may feel an overwhelming outside pressure for racial clarity. “People like a for-sure answer,” says Ferguson. “People like math because if you solve a problem, you have an answer, and that’s just the answer. I can’t just choose. It’s like asking, what half of yourself do you like better?”

“I don’t know if I have a concrete way to describe my ethnicity,” says Sarah Heikkinen, 23, a journalist from Cortland, NY. “I don’t know if I identify with being black or white, one more than the other. It’s hazy how a mixed person is supposed to define themselves; people are always defining it for them.”

Nearly two-thirds of people with a mixed-race background do not identify as multi- or biracial, according to a Pew Research Center study of Americans with at least two races in their background. There are a variety of factors—skin tone, hair color, eye color, where and how a person was raised—that may influence how a person of dual heritage classifies herself. In the Pew study, 47 percent of multiracial people who do not identify as such say it’s because they look and are perceived as a one race.

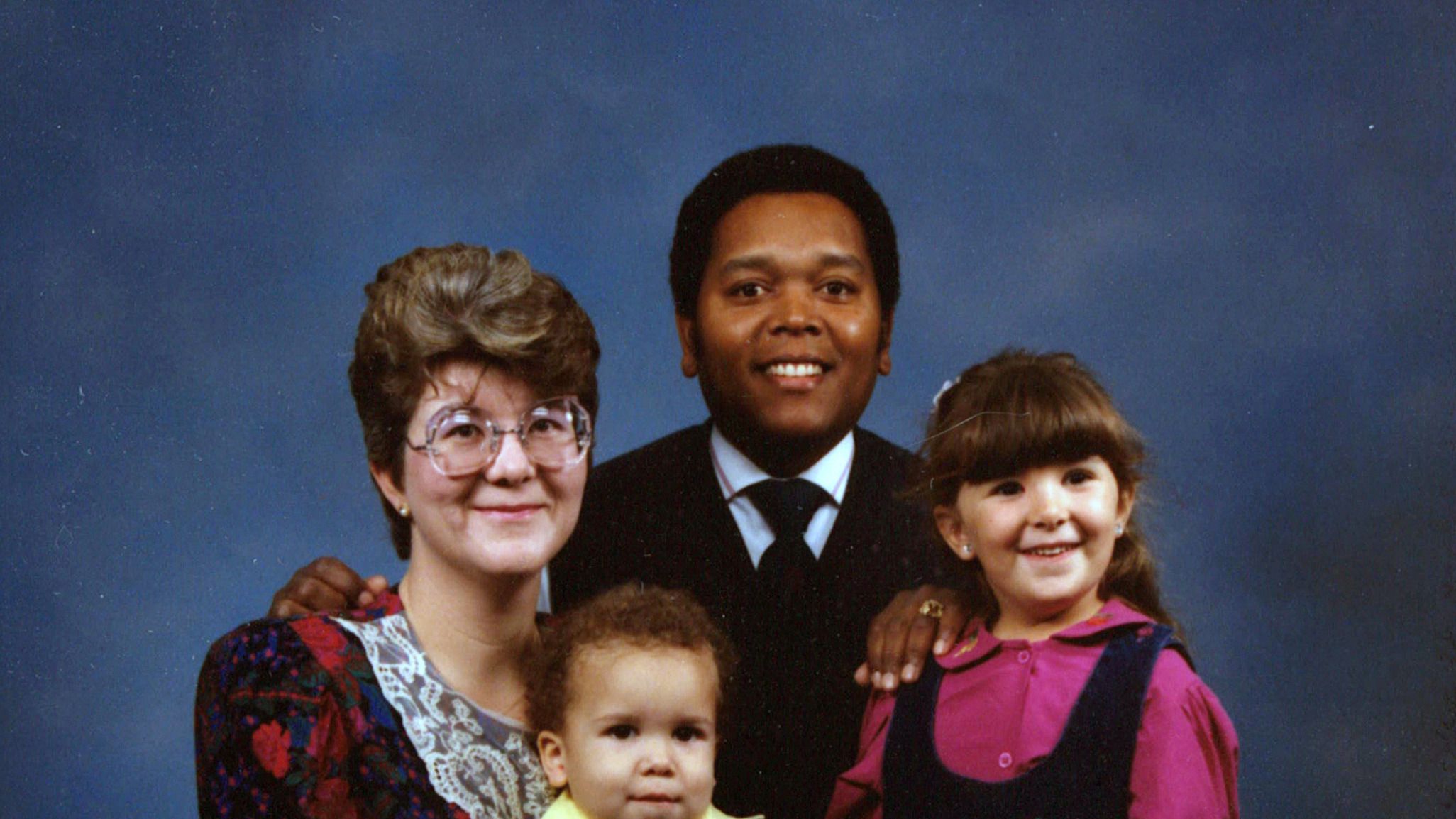

Heikkinen, whose mother is black and father is white, looks white: She has blonde hair, green eyes, freckles, and pale skin. Although her physical appearance doesn’t fit the expectation of “black” in America, she says she identifies with both races equally.

Growing up, Heikkinen struggled with hating the white part of herself. It’s the part of her that everybody sees—something she often resents because of the automatic assumptions people make. As a child she wished she had darker skin so she could encounter the same experiences as her mother, brother, and sister, who are all a few shades darker. She noticed the stares of other people whenever she was with her mom and siblings, as if she didn’t belong. Kids would ask, “Is that really your mom? Are you really black?”

“Is that really your mom? Are you really black?”

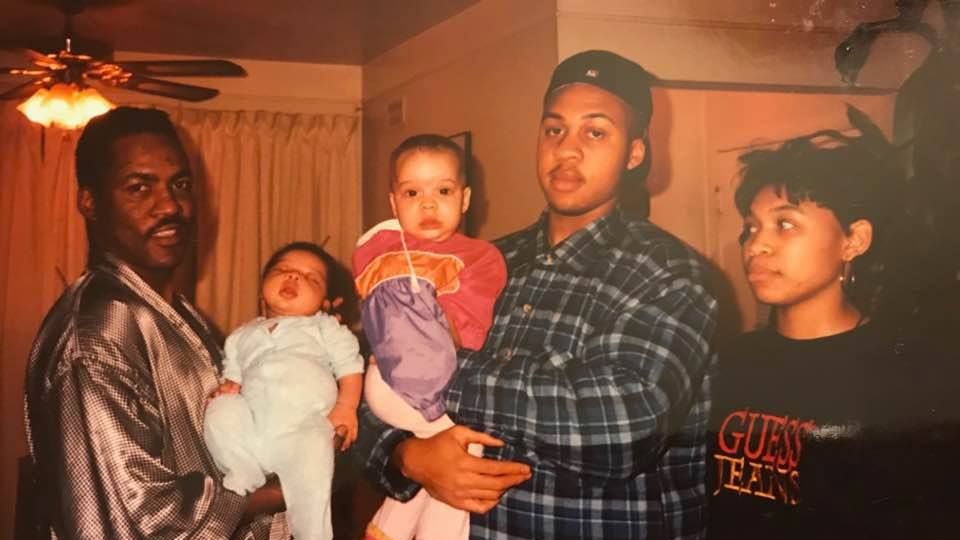

Ferguson has fair skin, brown eyes, and dark curly hair, but her older sister, Ashley Ferguson, is more white-presenting with pale skin, green eyes, and red hair. Ashley, like Heikkinen, sometimes felt alienated from her family because of her physical appearance. “My sister used to call me the white baby,” Ashley says. “They would joke that I was adopted because I didn’t look like the rest of my siblings.”

“We have an expectation in society of what a black person should look like, or what a white person should look like,” says Sarah Gaither, Ph.D., an assistant professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. “And if you don’t look like that, that’s disruptful.”

Gaither, who is biracial, says she’s treated like a “party game:” “‘Guess what race she is. I bet you’ll never guess,’ they say. I don’t match anyone’s expectations.”

I want to be fair to who I am, but it’s hard when society wants you to pick one,” says Kayla Boyd, 23, fashion and lifestyle blogger based in the Bronx, N.Y. For many identification factors (eye color, weight, country of origin) there can be only one correct answer. But race is an exception to the rule—and not all forms have a “check all that apply” option. It wasn’t until 2000 that the U.S. Census even allowed multiple selections for race.

“The big problem is that as a society, we think in either-or categories,” says Gaither. “You can only be one thing or another. You can’t be two things at the same time.”

“Being able to pass as a lot of different races means other people don’t know how to categorize me, but it’s also made me second-guess how to categorize myself,” says Boyd.

Combining black and white ancestry is about much more than how that DNA affects your skin tone or hair texture. The fraught history between the two races can present myriad struggles mentally and emotionally for those grappling with being a blend of both. It becomes intensely personal in a way that’s different from Americans of a single race. At first, Samantha and Ashley Ferguson’s maternal great-grandparents—who are from southern Mississippi—didn’t accept that their mother was with an African-American man. It wasn’t until Ashley was born, and appeared to be white, that they were “okay” with her parent’s relationship.

Heikkinen recognizes the privilege that comes with looking white: “A cop isn’t going to think I’m a threat.”

Sarah Sneed, 31, a guidance counselor from Newark, Delaware, thinks that—multiple boxes on government forms or not—there’s so much animosity between whites and blacks that choosing both is not an option anymore; it’s one or the other.

Lately, checking social media—and seeing the posts proclaiming white supremacy or belittling #BlackLivesMatter—has made Sneed more ashamed of her white side. “If I choose to be white, then I’m spitting on the history of my other side,” she says. “How dare I do that? And choosing to be black is like saying, ‘All white people are shameful,’ but I know that’s not the case either.”

All the shootings, marches, and riots have caused Samantha Ferguson to realize that we haven’t come as far as a country as people would like to think. “I don’t feel more hurt or pain for one group,” says Ferguson. “I’m not saying that everything that happens that’s racially unjust is white people’s fault or black people’s fault. It’s the decisions that both groups make; the morals and ideas that have been passed down for generations.”

Sneed identifies more as a black woman because she says she's more comfortable in her blackness than her whiteness, but that has presented its own set of challenges. “Because I look white, people think that I can’t understand what it’s like to be black, so I get embarrassed,” she says. “I read comments about being a strong black woman, and I’m like, I can’t be a strong black woman, because I’ve never had to be, because I don’t look black.” But the experience of being a “Becky” or a white girl isn’t something authentic to Sneed either.

She was raised by her white mother, but lived in an area with a larger black population. The way she talked was less “proper,” Sneed says, and the things that interested her were ones that resonated with the black community: She listened to R&B; and hip-hop. Sneed never felt comfortable, she says, with things she attributed as white, like having straight hair or loving country music. On the inside, she felt black, but on the outside, she looked white. That dissonance led to difficulty being accepted by her peers, and she wrestled internally over her identity.

A big part of the biracial experience is being treated—or not—like a black person in society.

Sneed worked hard to prove that she was black, using beauty products made for black women and going to a black beauty salon, but that, too, made her feel ashamed.

As humans, we have a built-in tendency to want to belong to groups, says Gaither. We are in search of family and friends because we’re social beings by nature. “For biracial people who are struggling with whether they’re white or black enough to fit in, that’s an added toll,” she says.

Typically for people who are half-white and half-black, a big part of their experience is being treated—or not—like a black person in society, says Gaither. “If you don’t have those features or skin tone that can lead to the tension and prejudice that a lot of members of the black community face, then there’s this awkwardness that mixed people face in claiming a black identity,” she continues.

“If you phenotypically look black, you don’t have the option of saying you’re white because you have a white parent,” adds Rockequemore, who, while biracial, identifies as African-American. “If you look white, you can identify in a full range of ways. You look ambiguous, so you have more choices of identity.”

Like Sneed, Heikkinen has spent most of her life having to prove her blackness to those who questioned it. It became common practice for her to show a picture of her and her mother to those who needed verfication. Gaither also carries around a family photo in her wallet as “proof” that she has a black father. And while constantly having to justify an identity is frustrating, Heikkinen recognizes the privilege that comes with looking white. “I walk into a store and people aren’t going to follow me around,” she says. “A cop isn’t going to pull me over and question me or think I’m a threat. It’s a privilege of blending in, of invisibility, in a way, because people just don’t notice you.”

Ashley Ferguson believes that people demand so much from mixed-race people because they are trying to make themselves feel more comfortable. “It’s terrifying for people when they can’t put a finger on you because you’re foreign to them,” she says. Depending on how someone is raised, they might need to put a person in a box in order to understand their version of that person, posits her sister, Samantha.

“I think putting me in a box is not the bad part,” she continues. “The bad part is putting me in a box with stereotypes. Not saying ‘you’re white,’ but ‘you’re white, so you sound proper and professional when you talk,’ and ‘you’re black, so you sound uneducated and loud.’ I think that’s the bad part—the other things in the box.”

“I can’t be a strong black woman, because I’ve never had to be, because I don’t look black.”

Samantha Ferguson, who graduated from Bowie State University, a historically black college, recalls being treated differently at that school because of her white features.

“Being a petite, white-presenting, female, when you go into the financial aid office to ask them for something, they don’t take you seriously” says Ferguson. “They just push you along, but you will not treat me differently. That’s not fair.”

Uncomfortable moments on campus didn’t end with the administration. Her fellow co-eds also judged her based on her perceived race. “I was dating black guys,” Ferguson recalls. “And there were a lot of girls who didn’t like me doing that because they didn’t see me as black.” She points out that the women who were rude to her weren’t actually interested in those men themselves. “They weren’t jealous, they just wanted to be hateful.”

Many people have opinions about how you should act, where you belong, and how you should categorize yourself when you’re biracial. But sometimes you simply can’t.

“You don’t know where you belong,” says Sneed. “I feel like I’m just floating. I am black. I am white. Being caught in the middle…you feel like you’re being pulled…it makes you uncomfortable all the time.”

Biracial people aren’t either-or, even if they identify as one race over the other. You can’t put them in a box or “solve” this problem. Asks Boyd: “I don’t want people to put me in a box, but it’s like, how do I break free?”

Like the great philosopher Natasha Beddingfield once said, "the rest is still unwritten." As a writer, I aspire to find the beauty in between the lines of the stories that haven't been written, yet (or the memes that haven't been discovered).