The Timely Return of Nancy Drew

When she made her literary debut in 1930, the intrepid teen detective validated the idea that girls could have guts, grit, and game. This month, as the convertible-driving, clue-deciphering, boundary-pushing sleuth lands on the small screen in the CW’s new Nancy Drew series, Michael Callahan makes the case that she was YA’s original badass.

The old attic was in complete blackness. Nancy knew the tarantula was coming closer to her, but she had no idea which way to roll to avoid its deadly bite. —From The Secret in the Old Attic, 1944

Nancy Drew had been through worse. In The Mystery at Lilac Inn (1930), her fourth adventure, her canoe capsizes, a bomb is placed under her bed, her car veers into a ditch, her cottage is set on fire, and she’s attacked underwater by a spear-wielding assailant. In the same book, she also survives an earthquake, a confrontation with a ghost, a kidnapping, and being tied up on a sinking, burning boat. The girl had grit.

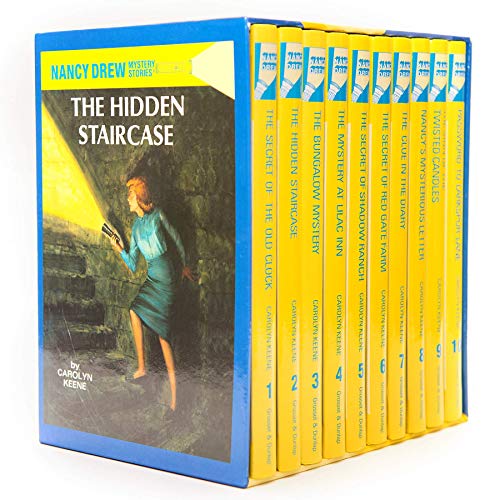

She is one of few fictional detectives—namely, Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot—to remain alive in the national cultural ether for a century or more. The Nancy Drew Mystery Stories—the classic 56 books that comprise the original canon—still sell more than 350,000 copies a year; there are currently more than 70 million Nancy Drew books in print, a figure that includes the classics as well as several modern spin-offs. The subject of a series of film serials in the late 1930s, the character was resurrected for weekly television in the 1970s and was the subject of both a feature film in the mid-aughts and a failed CBS pilot in 2016. Flashlight in hand, she’s now coming back to television in the CW’s brooding Riverdale-esque series Nancy Drew, which reimagines her as a disaffected crab-house waitress (sacrilege!) in the town of Horseshoe Bay (No River Heights? More sacrilege!) who has sex with Ned (now nicknamed Nick), her mechanic boyfriend, in the garage he sleeps in. (What’s a stronger word than sacrilege?) Her BFFs have also been radically made over: Tomboy George is now an Asian frenemy; pudgy Bess is now a thin, gorgeous rich bitch slumming it by waitressing too. But Nancy’s still chasing ghosts—in the first episode, she’s after a prom queen who plunged to her death from a gothic bluff. So there’s that.

But culturally, we’re experiencing a bigger Nancy Drew moment. A growing and eclectic phalanx of feminists, scholars, and chroniclers of pop culture has discovered what the four generations of girls (and a fair number of boys) who devoured those hallowed yarns have always known: Nancy Drew was YA’s original badass. There might never have been a Harriet the Spy, a Batgirl, a Veronica Mars, a Hermione, a Katniss, or a Tris if not for the first intrepid girl detective. “The total lack of boys and boyfriends and romance [in the original series] cannot be underestimated,” says Melanie Rehak, the author of Girl Sleuth, a 2005 cultural biography of the character. “It was really the first series that did that for a girl leading figure, where there was no romantic dimension to the story.”

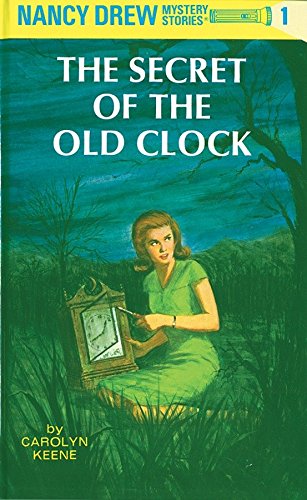

Founded in Newark, New Jersey, in 1905, book packager Stratemeyer Syndicate was a producer of mystery stories for children and churned out an endless stream of adventures featuring sunny yet daring young characters such as the Bobbsey Twins (launched in 1904), Tom Swift (1910), and the Hardy Boys (1927). In 1930, seeking a valorous, self-assured teenage heroine who would capture girls’ interest, founder Edward Stratemeyer created Stella Strong (mercifully renamed Nancy Drew by Grosset & Dunlap, the company that first published the books), the fetching daughter of a widowed attorney in the bucolic town of River Heights who spends her time solving mysteries.

Despite a slightly stiff, pious bearing, Stratemeyer, the father of two strong-willed daughters who would continue his publishing legacy, was quite progressive, something reflected in his early notes to one of his writers. “I see in your books you have a tendency to [feature] fearful fainting girls and women,” he wrote. “Better cut it—in these days the girls and women have about as much nerve as the boys and men. The timid, weeping girl must be a thing of the past.” He engaged a plucky Iowa writer named Mildred Wirt Benson to ghostwrite the initial Drew stories under the pseudonym Carolyn Keene. The result was rich, textured, and surprisingly complex chronicles that were hardly your run-of-the-mill missing-jewels cases. Wandering about haunted mansions, bridges, and even a showboat, Nancy confronted whispering statues and climbed creaky staircases; unearthed vexing clues in dusty albums and chimneys; and bested shifty, villainous characters with her keen eye, relentless pursuit of the truth, and fashionable wardrobe. Lithe, “titian-haired,” and affluent, she was also much more than that. It was unthinkable in 1930 that a teenage girl could be headstrong, intelligent, resourceful, inquisitive, and—when you really get down to it—a social-justice warrior. From 1930 to 1979 she roared through those 56 spirited tales in her jaunty blue roadster and, later, a convertible, fusing the traditional ideal of American feminine propriety (Nancy adores her dad, Carson, and dotes on her fretting housekeeper, Hannah) with the notion that a teenager could also bend the rules of young-lady decorum to outmaneuver crooks, all while keeping her suitors (mainly the perennially flustered Ned) on their heels with her insouciant emotional unavailability.

It was unthinkable in 1930 that a teenage girl could be headstrong, intelligent, resourceful, inquisitive, and—when you really get down to it—a social-justice warrior.

The stories made Nancy Drew an icon—and, perhaps inevitably, a symbol of controversy. In recent years, feminists have vociferously debated Nancy’s status as the golden girl of 20th-century tween literature. British journalist Ellie Duncan has criticized the books for always leading “back to the same crystallized vision of carefully tempered, inherently and damagingly qualified ‘achievable’ femininity.” In an essay published by the Kalamazoo, Michigan–based Arcus Center for Social Justice Leadership, titled “Nancy Drew and the Syndication of White Savior Feminism,” Chicago activist Kirsten Ginzky indicts the stories for, among other crimes, their portrayal of Nancy’s chums Bess, “a character primarily concerned with romance and food,” and George, “whose ambiguous queerness is all-but-confirmed through her plainness and athletic ability.” Still, in the end, Ginzky delivers a grudging verdict that the stories have been cited as “a beloved and formative influence by liberal women who have gone on to seek truth, power, and justice, while keeping within the frameworks of a system plagued by mass-incarceration, systemic racism, and state violence.”

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

They sure have. Oprah Winfrey, Diane Sawyer, Barbra Streisand, Barbara Walters, Cate Blanchett, Lucy Liu, Brooke Shields, Fran Lebowitz, Martha Stewart, and almost every female Supreme Court justice, just to name a few, have mentioned Nancy as a childhood role model. She was a huge influence for many women who entered politics. “I found myself paging through books in search of girl characters I could relate to,” says Hillary Clinton, who spotlights the protagonist in the recently published The Book of Gutsy Women, which she co-wrote with daughter Chelsea Clinton. “I was delighted when I found Nancy Drew. There’s so much to love: her bright mind, her adventurous spirit. And, of course,” she adds, “her affinity for wearing sensible trousers on the job.”

“The Nancy Drew books were among my favorites as a child,” adds Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi. “It was so wonderful to see a young girl who was in charge.” For CBS This Morning cohost Gayle King, reading the stories while growing up abroad in Turkey provided a dose of American culture and instilled a love of reading. “[Nancy] was fearless,” she says. “That was fascinating to me, that you could have a young girl like that who was fearless. I didn’t think, What a role model. I just thought, What a cool girl.”

Much of the credit for the character’s resonance goes to Harriet Stratemeyer Adams, who stepped in to lead the Stratemeyer Syndicate along with her sister, Edna Stratemeyer Squier, after their father died suddenly just after the first Drew mystery was published. Creative, independent, and feisty, Harriet was a Wellesley graduate and mother of four who spent weekends and holidays writing at her farm in the hills of Hunterdon County, New Jersey, and ran the Syndicate from 1930 until her death at 89 in 1982. If Nancy was ahead of her time, it was largely due to the fact that so was Harriet. “My grandmother did not consider herself a feminist but strongly felt women were equal to men in what they could achieve and that they should set their goals and go after them,” says her granddaughter Kimberley Stratemeyer Adams, a retired ophthalmologist. “I know she would be thrilled to see many prominent women citing Nancy Drew as an inspiration in their careers and lives.”

I was delighted when I found Nancy Drew. There’s so much to love: her bright mind, her adventurous spirit. And, of course, her affinity for wearing sensible trousers on the job. —Hillary Clinton

Like treasured recipes, the books have been passed down through generations of countless families. Nancy’s shrewdness, kindness, resilience, and unfailing moral compass are qualities readers have aspired to. “They were escapist and ennobling in a certain way,” says Tim Harr, Harriet’s grandson and an adjunct law professor at Georgetown University.

“People acting properly and getting a good result for themselves and other deserving people. It went down pretty easy.” The books also presented the world as an interesting and fascinating place, inspiring young female readers to explore it at a time when that was a pretty revolutionary idea. “I remember I used to look for mysteries,” recalls Noga Landau, creator of the just-debuted CW series. “I used to convince myself that something was going on with my neighbors next door, like they were trying to run a money-laundering operation or whatever. It planted storytelling in my head and the way I looked at the world, as if there were mysteries all around me. That made the world so much more interesting when I was a kid.”

As for the 21st-century updates, showrunner Melinda Hsu Taylor says, “We’ve modernized all the characters in their own ways, and we want to make them characters that anybody in the audience, including the queer audience, can relate to. Back in the day, she was an inspiration to so many girls who were being told you can’t be such and such. ... We want it to be inclusive, and we want to put that on screen. Creatively, it’s more exciting to tell stories that come from a lot of different perspectives and different backgrounds.”

The latest reimagining of Nancy Drew is hardly the first. The original Wirt Benson texts, often called “the Blues” for their blue-cloth bindings with orange lettering, were sonorous in language, description, and, alas, stereotypes. In 1945’s The Clue in the Crumbling Wall, Nancy meets a savvy policewoman, groundbreaking for its day.

Her description? “Lieutenant Masters was a charming woman; not the least masculine despite her businesslike manner.” Later, trying to locate a missing dancer, Nancy interviews “an old colored man,” Joe, a hospital janitor. He recalls, “Indeed Ah does remembeh dat gal! Ah felt pow’ful sorry when she went out o’heah in dat wheel chaiah.” The stories were later re-edited to delete such antediluvian tropes, but in the process they were made shorter as well; much of Wirt Benson’s mellifluous prose tumbled to the cutting-room floor. The resulting books, known colloquially as “the Yellows” for their butter-colored spines, are largely the ones still being passed down. Mothers, says author Rehak, “put the books away long before they had kids but were like, ‘If I’m going to save anything for my kids, it’s going to be these Nancy Drew books.’ ”

In 1984, Simon & Schuster acquired the copyright and spun off several new series, still written by ghostwriters as “Carolyn Keene”—an attempt to modernize her for the older teen market. These new books, whose covers all tend to look like advertisements for acne treatments, reduced Nancy to a crime-solving Carrie Bradshaw more interested in a suspect’s abs than his crimes. In 2012’s Stalk, Don’t Run, Nancy tangles with three Kardashian-like sisters as she works in a trendy cheese shop; housekeeper Hannah brings her smoothies. Out with Ned, Nancy laments, “No way could I spoil a perfect date with talk about carbon monoxide poisoning.”

Morgan McMann playing Nancy Drew in new series, premiering today on the CW.

But even as she’s reinvented, sometimes badly, the heart of Nancy Drew—what she means to readers whose childhood worlds she opened up with her breezy exploits—beats on, strong and constant. “There is definitely an awareness that we have a responsibility to generations of people who have found these stories beloved, and they have an attachment to it that’s very personal,” says Hsu Taylor. “I was at a seminar and this woman said to me, ‘When I was a kid in Illinois and there was no air conditioning, my mom moved all the mattresses into one bedroom, and we could check out all the books we wanted from the library. I picked Nancy Drew, every single book, and I read them all summer long.’ It was so vivid.”

The timing for a reboot is right, Hsu Taylor says, because Nancy represents nothing if not “emotional intelligence, which the world is in desperately short supply of these days.” Landau thinks the character also offers a refreshing break from the glut of two-dimensional superheroes cluttering film and television. Nancy’s superpowers, she says, “come from the things that are a little bit broken in us too. Putting Nancy on screen as a complicated character is what we hope conveys that to the audience. That it’s okay to draw strength from the parts of your life that are not perfect.”

Nancy’s return has devoted acolytes bubbling with excitement. “I’ve read the [pilot] script,” says Jennifer Fisher, president of the Nancy Drew Sleuths, the nation’s top Nancy fan club, which organizes an annual convention at a location from one of the books. “She’s determined. She wants to help people. She wants to get to the bottom of the mystery. And that’s the essence of the character.” For her part, she says, “I will definitely be watching.”

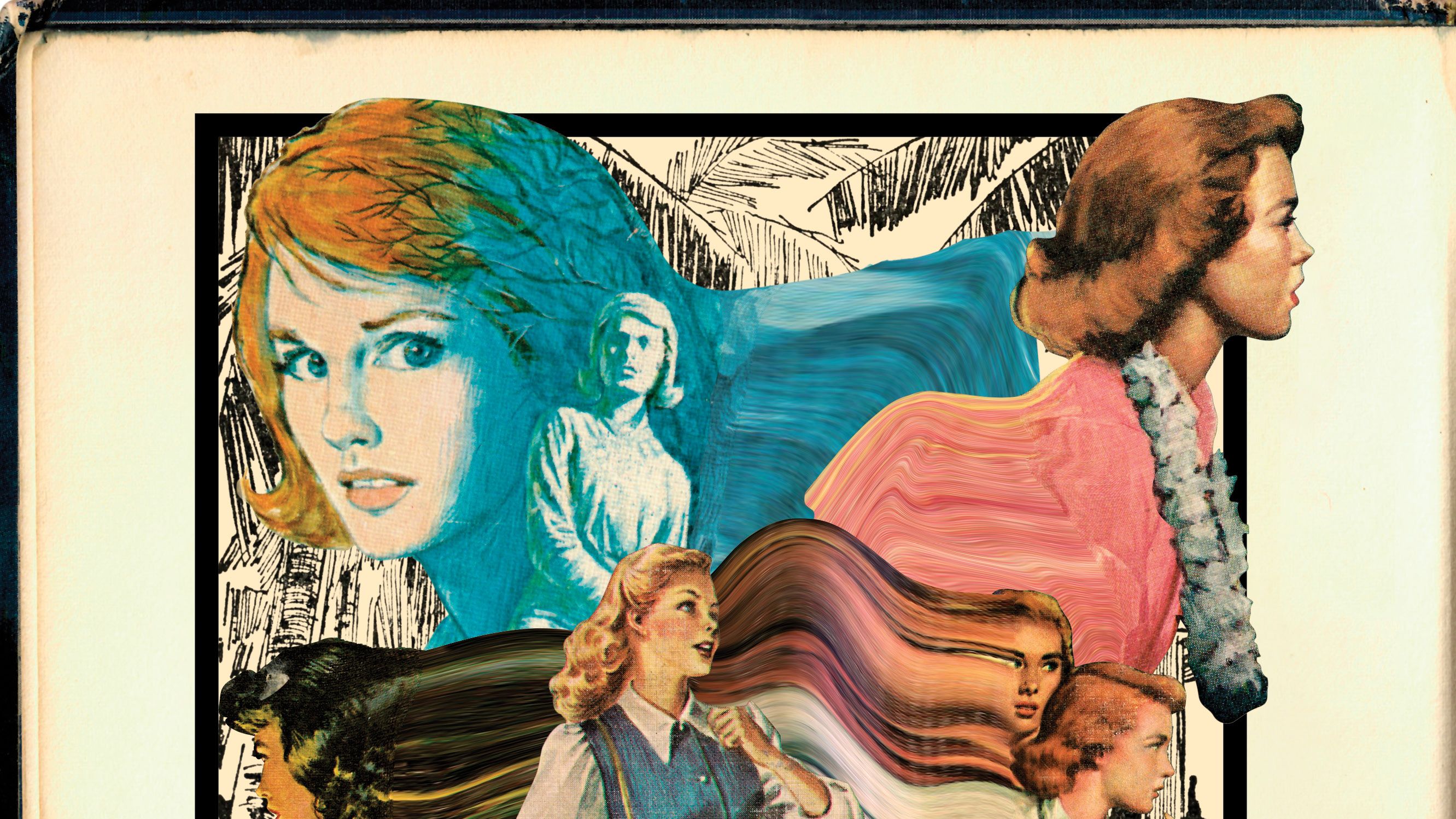

Lead Image: Nancy Drew in (clockwise from top left) The Mystery of the Ivory Charm/The Whispering Statue (1936), The Secret of the Golden Pavilion (1959), The Haunted Showboat (1957), The Clue of the Black Keys (1951), The Ghost of Blackwood Hall (1948), The Hidden Window Mystery (1956), and The Mystery at Lilac Inn (1961).

This story appears in the November 2019 issue of Marie Claire.

RELATED STORY