Being Black on Stage

Three of musical theater’s biggest stars pull back the curtain on the rampant tokenism and racism in the industry.

Musical theater has long had its “Black shows”: Motown, Dreamgirls, Porgy and Bess, The Color Purple, Ain’t Too Proud. It’s also long had its share of racism. For years, Les Misérables has been one of a few shows that employs color-conscious casting, with a revolving door of Asian, Latina, and Black leading women. But when it comes to coveted parts like Elphaba and Glinda in Wicked, Johanna in Sweeney Todd, and Cinderella in, well, Cinderella, for example, Black female leads are few and far between. Even when Black actresses have landed those roles and created firsts, it has often gone underreported.

But theater fans are hungry for the voice of the underrepresented. Consider that from July 3 to July 5, Disney+ was downloaded 458,796 times in the U.S., 74 percent higher than the average for previous weekends. Why? We’d venture to guess it had something to do with the fact that Hamilton—the Tony-winning show about America’s founding that features a cast of predominantly BIPOC in perceived “white roles”—hit the streaming service. (Of note: The musical itself is not free from criticism. It’s been denounced for glorifying slave owners, and creator Lin-Manuel Miranda was called out for not being a vocal proponent of Black Lives Matter—something he later apologized for.)

The industry is ripe for change. In early June, prompted by a nationwide reckoning with systemic racism and faced with the reality that COVID-19 could shutter several productions for good, the stage community came together on social media to share their experiences of feeling silenced, marginalized, and tokenized as they have pursued their Broadway dreams. Soon after, more than 300 people of color in the industry—including Viola Davis, Billy Porter, and Issa Rae—signed an open letter addressed to “White American Theater” demanding changes necessary to bring about a more inclusive environment. “We have watched you promote anti-Blackness again and again. We see you,” the letter read.

Join us in demanding change for BIPOC theater artists at https://t.co/LQuqHwVvLP. #WeSeeYou #TomorrowTherellBeMoreOfUs pic.twitter.com/xELs1oJR6KJune 9, 2020

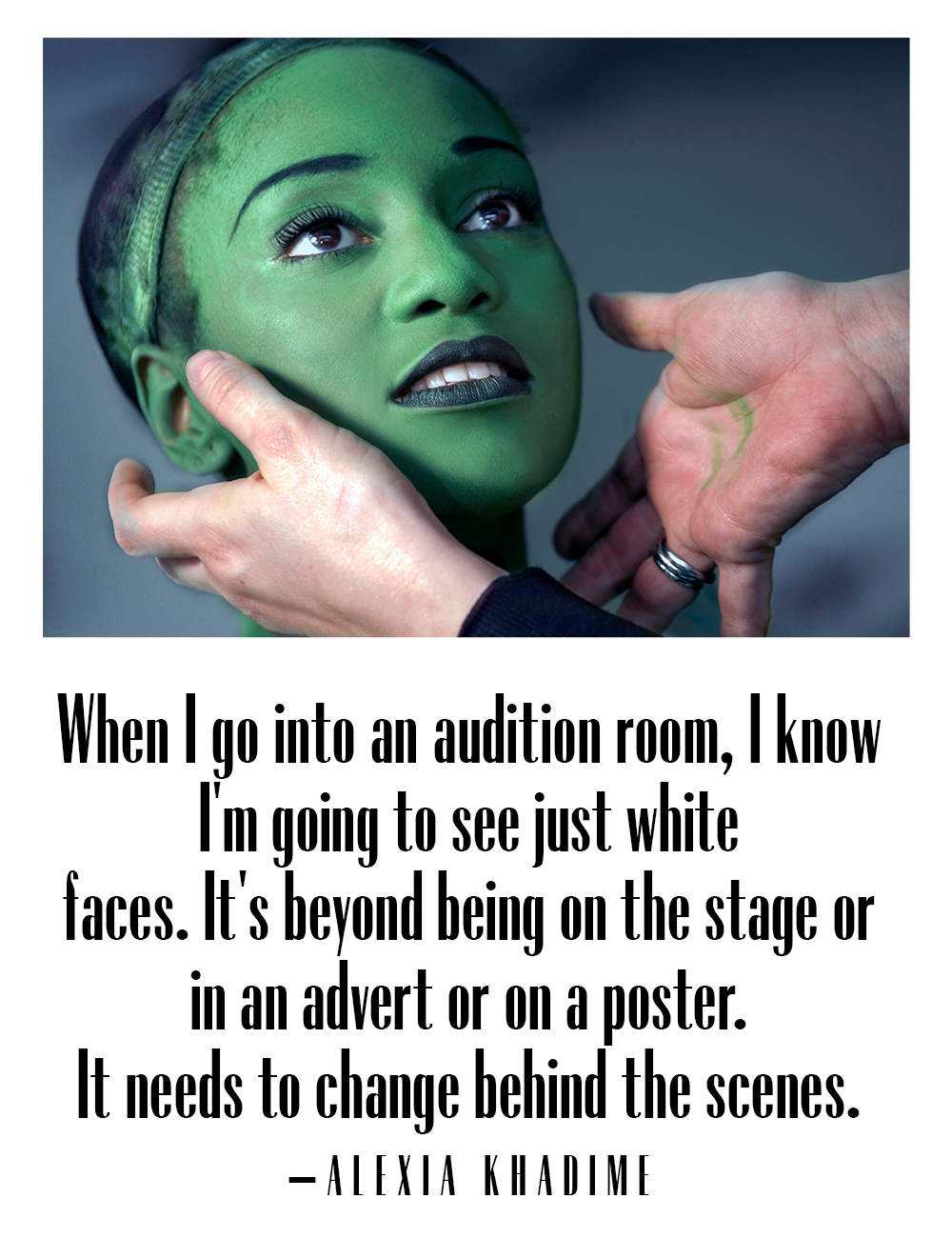

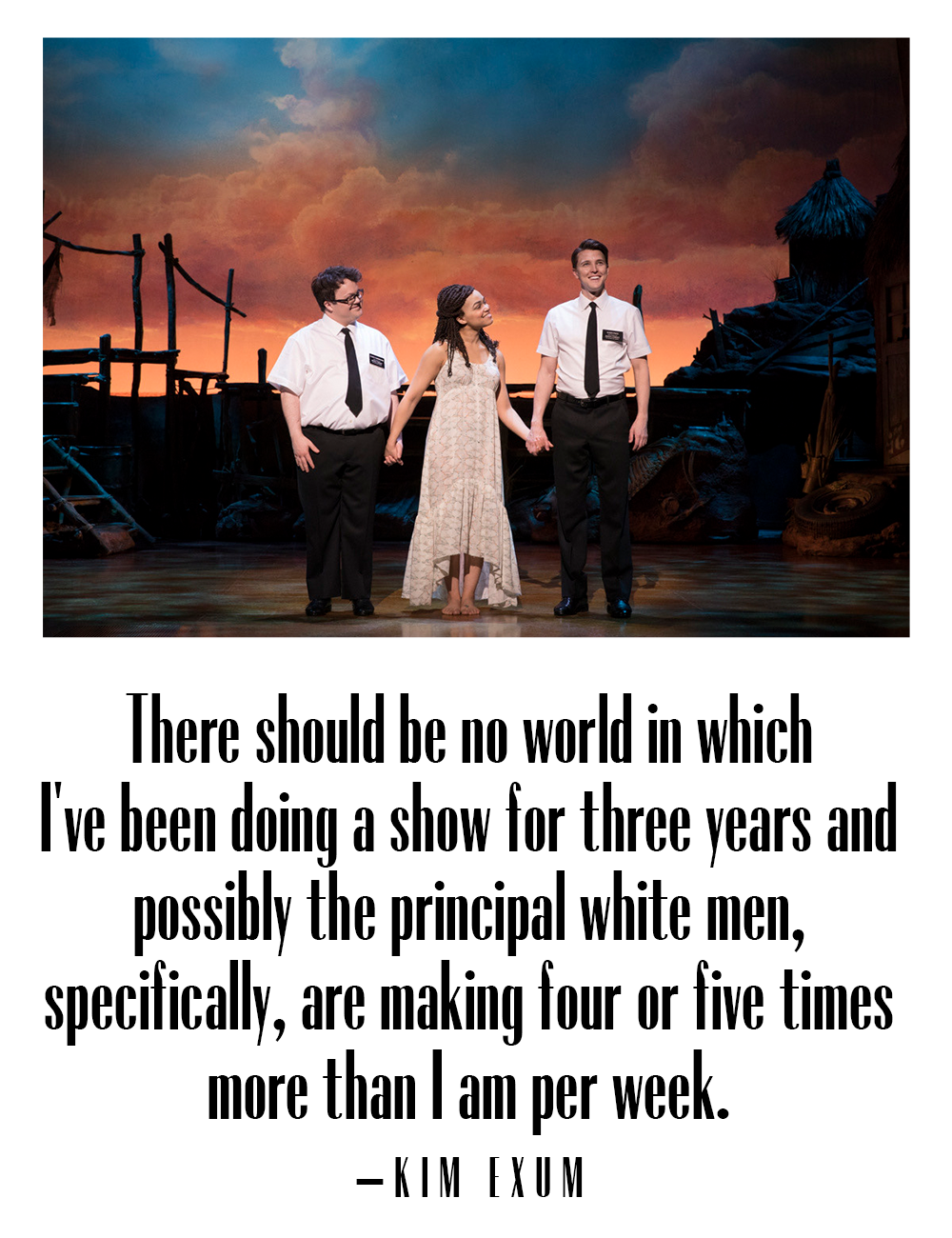

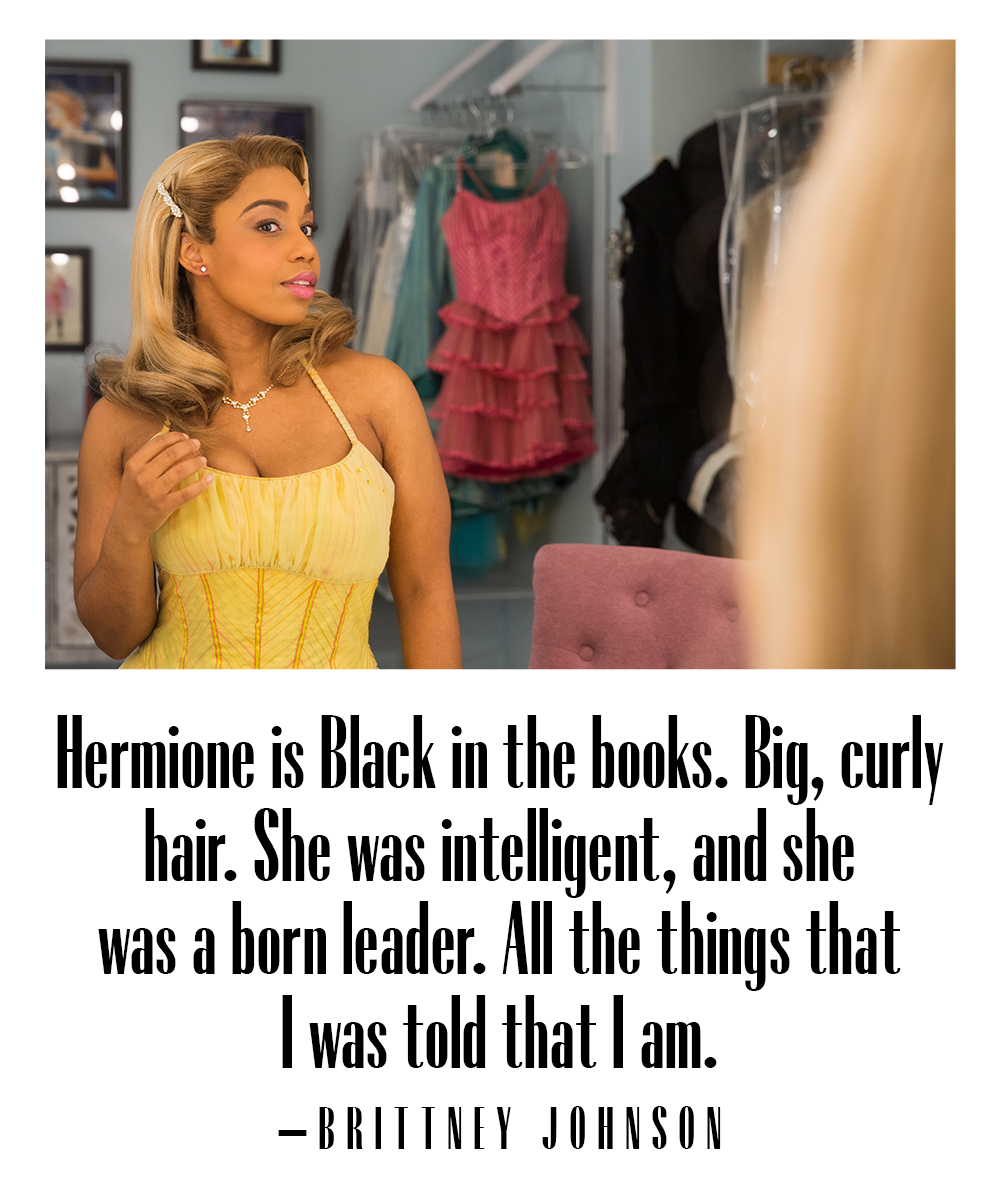

To spotlight the current challenges of being Black in theater, in July we held a virtual roundtable with Brittney Johnson, the first Black actress to play Glinda in Wicked; Alexia Khadime from London’s West End, the only Black actress to play Elphaba full-time in any production of Wicked; and Kim Exum, who currently plays Nabulungi in The Book of Mormon and cohosts Off Book: The Black Theatre Podcast.

The women shared their thoughts on discrimination on stage and behind the scenes, the wage disparity plaguing the industry, and the dream roles that have thus far been kept out of their grasp.

Marie Claire: Do you remember the first time somebody told you that you couldn’t perform because of your race?

Kim Exum: I did theater with Black kids in the inner city in Baltimore, so my first exposure to theater was with Black people doing white shows. My mind didn’t go, Oh, this is a white thing until I got to college. [The reaction to me as a Black performer] was more like “You’re not going to go far with this attitude, by speaking this way,” and trying to mold me into what they thought was industry appropriate.

Brittney Johnson: Like Kim, it wasn’t really until I got to college at NYU, where I would go and see shows and just never saw myself onstage. I would maybe, maybe see one person who looked like me. Usually in the back. Especially in school, when we would do scene studies in acting class...I played Tuptim [a Burmese character in The King and I]. This was my third year, and they still had no idea what to do with me. It didn’t even have to be my race, because there aren’t a lot of Black shows. But why can’t I play a made-up character?

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Alexia Khadime: [claps]

BJ: After that experience, I got so discouraged. Then In the Heights came out. That was one of the only reasons why I felt like I could keep going, because every single person on that stage pretty much looked like me. I saw that show 10 times on Broadway.

KE: In regards to not being able to do something because of how I look, I remember being in school. I’d shaved my head for the very first time, [and] peers and teachers told me, “You’re not going to be able to work with that. You need to have long hair.” Then, when I had a fro, [it was] “Why don’t you straighten your hair? You should get a wig.” And I said, “I’m not doing any of that.” I know a lot of Black women wear wigs to auditions to make casting see them as such, but I don’t see lots of white girls walking around with different wigs in their audition bags. Casting imagines them as that character. So if I walk in with pink hair, I would hope that you’d be able to do your job and use your imagination.

AK: It’s saying that we’re not good enough. Your skin and who you are is not good enough. And that is what has been preached for a very long time.

KE: Do I need to come in like a 17th-century costume for you to imagine me in the past? If it’s a slave or a civil-rights thing, then you have no problem imagining modern-ass me in that time.

AK: Sometimes [for auditions] they specifically want a Black girl, and [the call sheet] would say to come in your neutral accent. Then I would prepare for the audition and do it in my neutral accent. And it would be “Oh, um, could you...could you do it a bit more urban?” Because they have an idea of what a Black girl sounds like.

BJ: If you’re asking for a Black person who sounds Black, I am a Black person.

AK: Right here.

BJ: This is how Black sounds.

A post shared by Fourth Wall Live (@f_w_live)

A photo posted by on

MC: Have you ever turned down a job because of the lack of diversity?

KE: I’ve said no to things because I don’t like them or don’t think they represent me well, but I always say no at the gate, [when] I read the breakdown. I’m also never the token, because I’m light skinned. When they hire a token, they want you to be able to see the token from the back row where they put you. A lot of my work thankfully has been with other Black people. Even at Mormon, we’re half and half.

AK: I’ve never turned down work because of a lack of diversity. I’ve done Mormon, I’ve done Wicked. I’ve done Les Mis. I’ve done Lion King. So I’ve been in situations where there has been a mix of different ethnicities. But I’ve also been in a show where there’s only about two of us, and I was painted green. A lot of racism came with that because I was a Black girl playing the role that was predominantly played by a white girl. There were definitely people who made comments that I was taking away the white roles. At the time I played Elphaba, Obama was president. Then the comments were “Just because we’ve got a Black president doesn’t mean we have to have a Back Elphaba.” There was a point when Noma [Dumezweni] was going to play Hermione in the Harry Potter play, and that became a massive thing. It’s silly and ridiculous. In the book, she was never described as white.

BJ: And if we’re being really honest, Hermione is Black in the books. Big, curly hair. She was intelligent, and she was a born leader. All the things that I was told that I am. Hermione was Black.

AK: It’s a role. Let’s make believe. Let’s get some diversity. Representation is very important for the young.

KE: Elphaba is Black. If you’ve read the books, she’s an activist. She to me is a metaphor for Black women. So when I went to see Wicked, I felt like it was very watered down from what I saw in my imagination. I feel like those writers diluted her so that she would be more palatable and white.

AK: It’s a show that can and should have people from everywhere.

When they announced The Little Mermaid was going to be Black, were you shocked that some people on the Internet couldn’t accept that?

AK: Yeah. Using the hashtag #NotMyAriel. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing.

KE: Mermaids aren’t real.

BJ: People were trying to be like, “When I grew up, Ariel was the only one with red hair and she made me feel X, Y, and Z. And now you’re taking that from me.”

AK: There are Black people with red hair naturally too.

BJ: A huge part of why people get so taken aback when they see a Black person specifically, but any person of color, playing a leading role is because they haven’t seen it before. They need to be taught that we can be leads and at the center of the story. We don’t have to be a supporting character in a white person’s life.

AK: I don’t know what it’s like out there in the U.S., but when I go into an audition room, I know I’m going to see just white faces. It’s beyond being on the stage or in an advert or on a poster. It needs to change behind the scenes.

KE: A lot of times it’s producers working in tandem with casting. Casting’s not going to waste their time seeing someone—as fabulous as they could be—if they know the producers [don’t want it]. If they don’t want a Black Christine [in Phantom of the Opera], they’ll never watch your video.

AK: I was lucky when it came to going up for Elphaba. I was going up for something else at the time, and the casting director who was casting Wicked in the U.K. said to me, “Have you looked at material for Wicked?” And I was like, “What for?” Because why would I even think on that level? But she pushed and she didn’t stop. So I have to applaud that casting director.

MC: Is that the difference between—in the musical-theater sense—performative activism and true allyship?

BJ: Someone actually pushing and fighting for your hire is being an active ally. You bringing me in is wonderful. But you bringing me in and being taken through all of the rounds only to be told that “We went in another direction” over and over and over—and that direction is always white—you have wasted my time.

AK: Don’t call me in to tick a box, right?

BJ: And I think a lot of that is happening so that they can say that they looked and they tried, but they couldn’t find anyone. Which just isn’t true.

MC: Is there something you wish that people knew about your industry that isn’t talked about?

KE: The wage gap between women and men and Black people and white people [for] principal salaries. It’s something I’ve discussed with other Black women. It’s something that I recently brought to the attention of my producers as well. I feel like we could justify the wage gap by saying that [playing] Nabulungi [in The Book of Mormon in 2016] was my first Broadway show—I’m green and don’t have many credits. But at the same time, there should be no world in which I’ve been doing a show for three years and possibly the principal white men, specifically, are making five...four or five times more than I am per week.

A post shared by kim (@kim.exum)

A photo posted by on

AK: Mm-hmm.

KE: I bow third [from last], I bow third. I may as well bow with the ensemble. I told the producers, “When I was pregnant, I saved up money to be unemployed because there’s no maternity leave.” So I was accepting unemployment, which was $450 a week [at the time]. I had some savings. I had to go on WIC. I had to get food stamps. I’m technically a “Broadway star.” I highly doubt that the white guys would have to do that. It’s a hard thing to prove because you feel like it’s your fault. It may be my fault for accepting the low wage, but I didn’t know that it was low until I got there.

BJ: And that goes back to your earlier question, Have you ever turned down a job because of the lack of representation? And the fact is, there’s so few opportunities that I’m not able to just turn down things. I will say that recently, I turned down an audition specifically because I thought they needed to be seeing people of that race for that role. Even though I knew that white people were going to audition. But I said no because if the shoe was on the other foot, I would want someone to do that for me.

MC: That’s very gracious of you. But what if a white woman doesn’t forfeit this audition for someone of color, as the role was intended?

AK: That’s that privilege [laughs].

BJ: Well, you’ve never suffered as a result of being white. You’ve never been excluded from anything because of what you look like or for something that you have no control over. When Hamilton was casting for mostly people of color, people were up in arms. “This is discrimination!” No. You’ve just never not been the first one that they’re looking for.

AK: In The Lion King, some people in our industry said, “Why can’t there be a white Nala?” It’s one show you’re talking about.

KE: They will just replace you. For the guys, they’ll be like, “We need you, and we’re going to give you as much money as possible to stay.” They’ll just get another one of me. I don’t need to be paid like Audra [McDonald], I don’t need to be paid like Nikki Renée Daniels. But don’t offer Black girls $400 above minimum for doing a principal role.

BJ: The only power that you have is to say no. And sometimes you are in a position where you can say it, but most often you’re not. You’re made to feel like you have no power and you just have to take whatever they give you. Although I do think that is changing. I do hope that it becomes a collaborative offer, so that we don’t have to feel like we are fighting for our worth. I do think that’s part of the reason why, when this movement started—especially in our entertainment community—a lot of my white colleagues were quiet, because they were nervous that it’s going to affect their current job. I have no interest in you losing your job. What I’m asking for is to be on an equal playing field when we’re auditioning for the same job.

AK: 100 percent.

From left: Alexia Khadime as Éponine in Les Misérables, Kim Exum as Nabulungi in The Book of Mormon, Brittney Johnson as Glinda in Wicked.

MC: The clip of Viola Davis talking about how people called her “a Black Meryl Streep…there is no one like you,” and she responds with, “If there’s no one like me... you pay me what I’m worth.” Thoughts on that?

BJ: We’re labeled, like, Black Glinda and Black Elphaba. I’m just flat out Glinda.

KE: I’m going to start saying things like, “Oh my God, white Glinda, white Elphaba.” Start putting “white” in front of all of the roles.

AK: The beauty of our work is that different people are able to step into the role, and we see a new interpretation. Your background and who you are is what makes the role you step into slightly different, and that’s the future of it. That show is able to stay alive and never be stale. And that’s often forgotten.

BJ: I would almost rather you say, “We are looking for a very specific look.” And you can’t say that because then you’d have to hear yourself [being] racist. But then, when they see you [for a part] and your white colleagues don’t get it and they say, “Well, Black’s in right now, so of course you’re gonna get it…”

KE: It’s such an entitlement. Your time will pass. What you’re saying is people who look like us are trendy, and you’re just waiting for us to go out of style so you can get more jobs.

MC: And you’re saying, “I’m not like high-waisted jeans. I’m not going away.”

BJ: It also discredits the fact that I’m qualified. Ethnic is in. No. I worked hard and studied just like you did. So every time you get a role, would you like me to say, “Oh, it’s cause you’re white?” There’s a double standard. There’s already a double standard for life being Black; there’s a double standard in life being a woman. When do we get to win?

AK: Black women are for some reason at the bottom of the totem pole.

KE: I highly doubt that Audra McDonald is the highest paid performer on Broadway. But if she were a white man, Audra would be the highest paid. Hands down. But I don’t know, I mean, Audra, if you’re [reading this]…let us know.

MC: I saw Sweet Charity on Broadway and remember the Black costar outsang the white lead by a mile. I was so young and conditioned to see just white leads that I didn’t even think, Oh, it could have been switched. Moreover, I’d never seen two Black leads together.

AK: One at a time, per title.

BJ: Try to imagine the last time on Broadway or in a movie you saw two Black leads who were counterparts in a show that was not a Black show. Or where the entire cast wasn’t Black. Try to name one.

MC: Let’s say you could do whatever you wanted. What would your next dream role be?

BJ: I mean, we’ve been saying it a lot... I want to play Christine in Phantom. I’ve wanted to for so long. I sing those songs in the shower.

KE: Now that I know that it’s possible, I think that I would love to have a stab at Glinda, even though I’m not super, super trained. I would also like to play one of the men in Hamilton, like Hercules Mulligan or [laughs] Aaron Burr.

BJ: I’d love to do Eliza in Hamilton too, if we’re wishing!

KE: We could be the Schuyler sisters.

AK: It could happen! Ultimately, [my dream is] to do a role where I’m just a person, as opposed to “the Black girl.” I don’t want to just be your maid or the prostitute, thank you. I want to be an everyday person. Can I just be a woman? Not saying that I’m taking away from being a Black woman, but rather than the stereotypical roles, you know? It’s not that you have to be the maid in order to make it or win an award. No discredit to anybody who has in the past. The problem is that these are amazing actresses and actors who’ve done these roles. Why did they only get recognized when they were playing the drug dealer or the maid? So yes. That’s the dream of mine: to just play a person. A woman.

BJ: That would be a beautiful, beautiful thing.

This post has been updated.

MORE FROM OUR AUGUST ISSUE