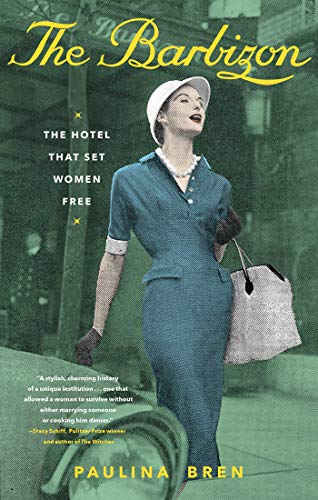

Inside the Barbizon Hotel for Women

A combo of charm school, sorority house, and dorm, the Manhattan landmark was the ultimate room of one’s own for many famous women, as this new book details.

From the Jazz Age to Disco, the Barbizon Hotel was a refuge for women fleeing their staid pasts and seeking an exciting, fulfilling Manhattan life. Opened in 1928 on Lexington Avenue and 63rd Street, “the Dollhouse” as it was later nicknamed, was a so-called “respectable” hotel for women, one of several in the city. It was not a boarding house, known at the time for scratchy black horsehair sofas and dull communal dinner tables—a seedy Victorian vibe—or a co-ed hotel, where one might, god forbid, be confused for a woman of loose morals.

According to this fascinating new book The Barbizon: The Hotel That Set Women Free by historian Paulina Bren, after the Roaring Twenties, single women were flocking to New York City in unprecedented numbers and expecting to have careers just like men did. The Barbizon Hotel for Women advertised itself as the right place for a young respectable career woman to meet the right kind of people, for around a reasonable $11 dollars a week (about $165 today). Vanity Fair called it “a genteel fortress” with “the feel of a luxe convent.” Prospective tenants needed three references and were graded according to their looks, manners, and style. Ali McGraw, Grace Kelly, Lauren Bacall, Liza Minelli, Joan Didion, Cybill Shepard, Candice Bergen, and Sylvia Plath were among those who passed through.

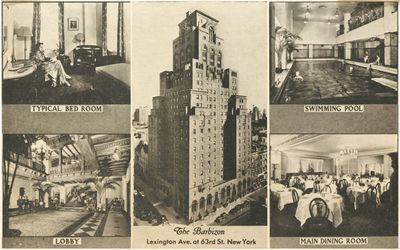

During the pre-contraception days (the Pill was legalized in 1965), there was a feeling in society that “nice” girls—and their virtue, their reputations—needed to be protected. And, for many, that safe space was the 23-story edifice of coral-pink brick and sandstone façade with Romanesque, Gothic, and Moorish embellishment. It housed 700 guest rooms just big enough for a single bed, a petite easy chair, and the then-impressive technology of a radio built into the wall. Most rooms shared hallway bathrooms, dormitory-style. There was a library, a pool and gym, a roof garden, and studios to practice painting or singing arias. Discreet entrances off the lobby led to a coffee shop, a bookstore, and a few other shops that were all the well-heeled and well-bred woman could supposedly want. A mezzanine over the lobby allowed women to scope out the dates coming to pick them up. At afternoon tea, a lady played a pipe organ. It was the kind of place where conservative parents might be okay with sending small-town daughters, since there was a gatekeeper doorman and eagle-eyed ladies at the front desk who enforced the hotel's most important policy: no men allowed upstairs at any hour of the day or night. After sundown, even the elevator operators were women.

Models hang out in the Barbizon lobby (smoking indoors, no less!) in 1977.

The Stork Club, one of midcentury Manhattan’s storied nightclubs, invited Barbizon women to eat and drink for free, because the mystique of the hotel was that it was brimming with beautiful women. The Barbizon (named after the French school of Naturalist painting to create an artsy vibe) was also where the editors of literary fashion mag Mademoiselle decided to house the winners of its annual college Guest Editor program. The 1953 cohort included Plath, who dramatized her 1953 summer there in the classic feminist novel The Bell Jar. She called her fictional hotel the Amazon. Plath ends her semi-autobiographical tale with the heroine going to the rooftop and flinging her prized wardrobe, collected for the summer stint as a fledgling magazine editor, off into the Manhattan nightscape. IRL, Plath left the Barbizon after the Mademoiselle program was over, went back to the family home in Massachusetts, and overdosed on pills in a crawlspace, where, after a nationally publicized search, she was found barely alive.

The “Katie Gibbs girls,” who attended a white-gloves secretarial school, had reserved rooms. Ford Models put up recruits there. Grace Kelly was an awkward brunette drama student wearing heavy glasses. Aspiring dancer Jaclyn Smith (of TV’s original Charlie’s Angels) hung out with model Dayle Haddon. Cloris Leachman, fresh from the Miss America Pageant, stayed there on her way to stardom. Judy Garland was said to frantically call the front desk to keep tabs on daughter Liza Minelli. Peggy Noonan, presidential speechwriter, did a stint. Little Edie Beale (before Grey Gardens fame) lived there from 1947 to 1952. Mademoiselle also brought Joan Didion, Diane Johnson, Ali McGraw, Meg Wolitzer, and fashion designer Betsey Johnson.

A woman leaves the Barbizon in 1981; it was the end of the women-only era.

The Barbizon that Bren describes is conspicuously white. She suggests that the first Black woman to stay there was probably Barbara Chase-Riboud, who, she says, in 1956 was also the first Black Mademoiselle guest editor. Chase-Riboud went on to be a noted poet, author, and artist. Phylicia Rashad stayed in 1968, aged 16, for a stint at the prestigious Negro Ensemble Company, a groundbreaking theater company run by and for Black people. It would have been interesting to learn more about actual rules the hotel had regarding women of all races. There are mentions of how Chase-Riboud was supposedly asked by Mademoiselle editors to step out of meetings with Southern advertisers and a semi-joking reference that she wasn't told of the existence of the Barbizon pool, but race relations are somewhat skimmed over. I would have loved to know the experience of other women of color or minorities at the Barbizon. Was it strictly WASP-only, or were there Jewish, Muslim, Italian-American, or Asian women in the guest log? How did race and class play into the grades that front-desk guardians gave to women who applied? Also, one of the foundations of the Barbizon's appeal, as per Bren’s book, is that no men were allowed. There is little talk about guests’ same-sex relationships. Were there ever any openly gay women in residence?

In 1981, the hotel was struggling financially and changed its policy to let in men. By then, young women (and their families) presumably didn’t have the same worries about reputation. Feminism was having its Second Wave—with Roe v. Wade, Ms. magazine, and the E.R.A. The liberated women who might otherwise stay at the Barbizon could have jobs and credit cards and bank accounts and apartments of their own. They could even cohabit with a significant other—not necessarily in wedded bliss. In 2005, after enduring a series of owners (including Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager, of Studio 54 nightclub fame), the building was turned into luxury condos, housing Ricky Gervais and the chairman of Meow Mix cat food, among others.

A 1930s postcard advertising the Barbizon's civilized attractions.

Speaking of catty, Bren threads through the book the story of “the Women,” those who never managed to leave the Barbizon for that dream of a suburban split-level, a penthouse apartment, or a palace plus Prince Charming (in Grace Kelly’s case, His Royal Highness Rainier III of Monaco). With rent-controlled or -stabilized apartments, the Women were unbudge-able. In 1957, Gael Greene, who had stayed there as a Mademoiselle guest editor and was later the New York magazine restaurant critic, reported for the New York Post on the “Lone Women,” who remained at the Barbizon, presumably not having made their fortunes or started families. Those stay-on renters were eventually herded into an un-zhuzzhed part of the building, where the remainder continue to live to this day in shabby-sorority splendor.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

If you love the glimpses of the long-ago New York City of Midge Maisel and Peggy "Mad Men" Olson, you will want to read this true tale of a bygone New York City.

Maria Ricapito is a writer who lives in the Hudson Valley.