Grace Byron Is Telling Her Story in Her Own "Demonic" Way

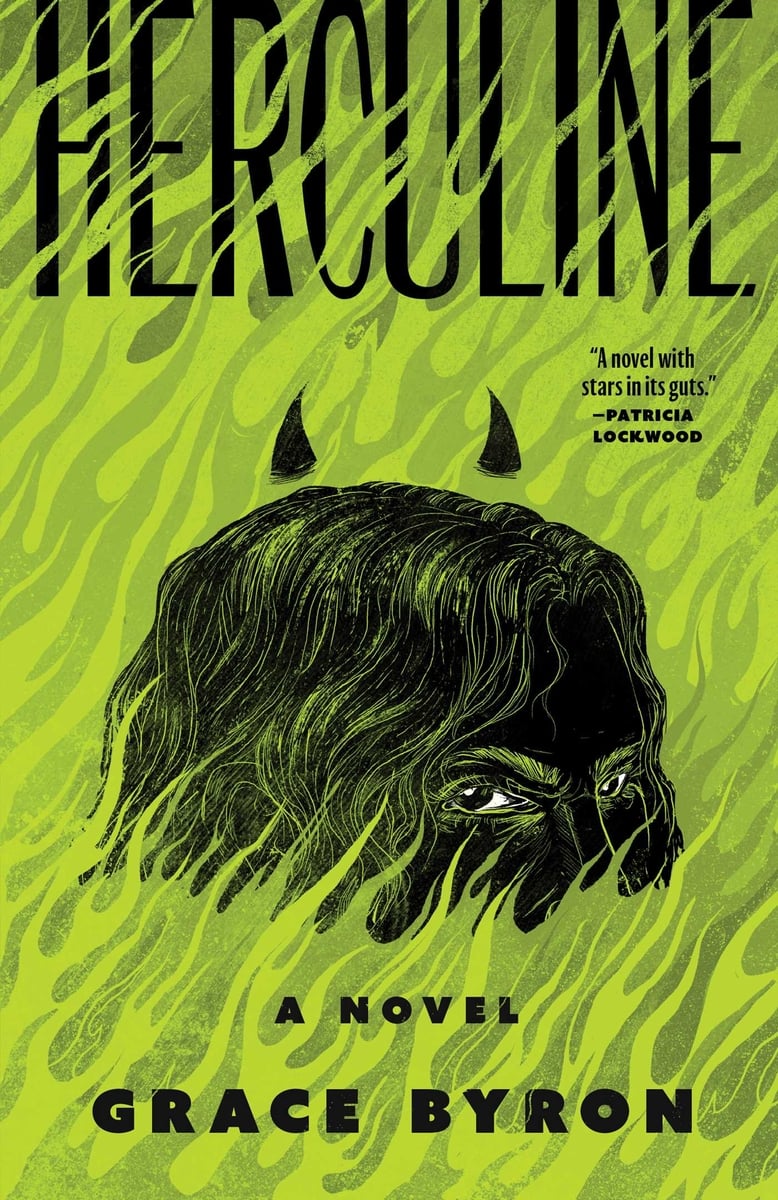

The author’s debut novel, 'Herculine', challenges purity politics and explores the dream of queer communes.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Marie Claire Daily

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Sent weekly on Saturday

Marie Claire Self Checkout

Exclusive access to expert shopping and styling advice from Nikki Ogunnaike, Marie Claire's editor-in-chief.

Once a week

Maire Claire Face Forward

Insider tips and recommendations for skin, hair, makeup, nails and more from Hannah Baxter, Marie Claire's beauty director.

Once a week

Livingetc

Your shortcut to the now and the next in contemporary home decoration, from designing a fashion-forward kitchen to decoding color schemes, and the latest interiors trends.

Delivered Daily

Homes & Gardens

The ultimate interior design resource from the world's leading experts - discover inspiring decorating ideas, color scheming know-how, garden inspiration and shopping expertise.

In Grace Byron’s, Herculine, the unnamed narrator is a bitingly funny critic of New York culture. She speaks of “hot freelance girls,” a specific media breed seemingly made in a lab with a “cloud of Santal 33 and secondhand Prada” to incite envy. Byron's own time in the freelance trenches—she made a name for herself in the media world penning incisive cultural criticism for outlets like The New Yorker, Vulture, and on her Substack—makes her know these kinds of girls all too well.

So reading Herculine feels like a natural extension of Byron’s work. In it, her unnamed heroine is living adrift in Brooklyn; her demons literally accompayning her as she works at a children’s clothing store while dreaming about being a writer. As she unearths her various traumas, she reconnects with her ex-girlfriend, Ash, who has started an all-trans girl commune (named Herculine) near her hometown in Indiana. The pull of both Ash and the ideal of trans community brings the narrator there, where it becomes clear that her demons aren’t the only ones at the commune.

Ahead of the book’s October 7 release, Byron spoke to Marie Claire about writing her debut novel, the idea of trauma bonding, and how it feels analyzing trans life in this political climate.

Marie Claire: What was the first inspiration for Herculine?

Grace Byron: I was trying to write a memoir, and I failed. It felt important to try and figure out a way to think through similar themes, but introducing a sense of play, fantasy, and surrealism felt like a helpful way to work through it. I always wanted to work on fiction, and it ended up having to circle back after I spent some time thinking through how to approach it.

MC: This novel straddles a lot of lines between horror and fantasy. Why was that a draw for you?

GB: I grew up reading a lot of fantasy, more than horror. I read Narnia, A Wrinkle in Time, and all the quasi-Christian fantasy books. I wasn't really expecting to do horror, and it crept up and felt like a natural way to think through trauma. I read Gretchen Felker-Martin’s book Manhunt, and that was just a big light bulb moment. At first, Herculine wasn't necessarily going to be a horror novel. The demons took over as I was writing.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

MC: You are from Indiana. Was that part of having this setting between New York and then the narrator going back to where she was from?

GB: You write the book that you don't want to write; you end up confronting all the things that you don't want to write. I didn't really want to write about New York, but I did, through this backdoor way of writing about personal stuff, including Midwestern culture and what it's like to be queer or trans in the Midwest, and the guilt and confusion around moving away. It felt important to me to represent the Midwest and not just writing another New York novel.

A post shared by grace byron (@emotrophywife)

A photo posted by on

MC: Herculine is so funny on top of being frightening. There are so many incredible phrasings like “hot freelance girls,” “trans girl actress,” and “female small business owner” that are just so succinct in knowing exactly what you are talking about.

GB: I wrote this at a time when I was less accomplished. I was really working through jealousy and envy, and so much of gender for cis and trans people is about ambition, envy, jealousy, and desire. There's this way that the narrator is thinking, even if she's not really getting anywhere with her thoughts. That bitterness felt like a narrative engine and interesting to use as a propulsion for thinking about belonging and community, and the way that she is unable to build alliances or friendships with people because she can only see them as people she wants to be or as people she wants to conquer. A lot of freelancers feel it is competitive, and similarly, gender can be competitive. The bitterness lent itself to this biting humor that felt like the only way to write about it. I didn't really want to write a more sappy trauma story. I would rather obliquely reference the Trans Girl sob story and have some bile come up rather than give it in a sickly sweet way.

MC: That outsiderness that the narrator feels is what brings her to the commune and back to her ex-girlfriend Ash. Their relationship is interesting because it's so toxic, but they're also tied together in terms of discovering who they were and transitioning at similar times. How was it mapping out that relationship?

GB: It felt important to sort of write about T for T heartbreak in a way that strips away some of the naivete and gets into the more gritty and painful parts of that, which there is a precedent for—I think, both Torrey Peters and Gretchen Felker-Martin have written about that. To me, such a large part of the book is how the very alliances that you want to have and the community you want to have can still hurt you. Someone recently, in an interview, was like, ‘I feel like Ash is the villain.’ And I was like, ‘That's so crazy to have a trans woman be the villain in a book about trans women, especially in this political climate.’ But I always want to dig into those uncomfortable things. There is a danger in portraying her as the villain, for sure. It is a delicate balancing act, but I don't necessarily see that there's a clear-cut evil person; perhaps the demons are. She really wants it to work with Ash on some level. I think those things are messy and painful. She goes to this commune, skeptical but hopeful, and ends up still being let down even though she wasn't ready to give it her all. Her actual friends end up being the imperfect but hopeful vessels for community.

Such a large part of the book is how the very alliances that you want to have and the community you want to have can still hurt you.

MC: What was the idea for Herculine being this idea of an all trans women commune, looking for community, and then for it to all go completely awry?

GB: There's a trope about the queer trans back to the land commune, and I wanted to take that not fully at face value, and explore how that can still reinforce the same social hierarchies and oppression that the outside world does. You can't escape your baggage, which isn't to say that being a separatist is an entirely wrong politic, but to explore the messiness of that and how that can still fail you, and that it's not a foolproof strategy to escape pain or heartbreak or disaster. That felt like an interesting vessel for thinking about trauma and politics and the way that you bring all of your pain with you wherever you go.

MC: I love the line towards the end of the book about how Ash thinks they fell in love because of their mutual trauma.

GB: Trauma bonding is such a confusing, but continual trope in queer culture, and what is the right way to form a friendship or the wrong way to fall in love? This book takes the fact that inevitably trauma will inform your life, but there are ways that it can lead to negative consequences if you let it too much. The book is about how trauma can distort love or friendship, and it's a book about what love isn't more than it is a book about what love is.

A post shared by grace byron (@emotrophywife)

A photo posted by on

MC: There’s a line in the book that’s “So much of transexualism is the divulging of history. It’s not a gift so much as a bomb we’re all passing to one another.” I’d love to hear a bit more about that.

GB: It's always really nerve-racking to write into these more tricky parts of trans life and embodiment that other people might read and weaponize against us in this political moment. But for better or worse, that is what is interesting to me as a writer. I'm glad that a lot more trans writers are starting to try and write about poorly behaved trans women. And a lot of my short stories started as well, what if someone trans did “the worst thing,” and we follow that person and treat them as a whole human anyway. That line in particular is reflecting on the idea of trauma bonding and the way that when you're trying to offload your pain through confession. Like maybe this time if I connect with someone or this time I befriend someone, I can tell them my burden and it'll be done. I'll have given it away. I'll have given the ticking time bomb to someone else. And it just doesn't work like that.

I think so much of the way that a lot of queer and trans people can befriend each other is like, ‘Here's my shitty history. What was yours?’ That can be both a sort of cheat code or a shortcut into intimacy that sometimes isn't always the best…It's another one of those double-edged swords that felt interesting to write about.

MC: You wrote a piece for The New Yorker about the state of trans art right now, and everything with trans rights is scary at the moment. How is it exploring that with the novel?

GB: I find the idea of purity politics in minority art to be really brutal and not fair and not interesting, not how art works. I always want to be pushing against that. Rose Dommu said something similar in an interview recently about her new novel, where she was talking about anything I can do to push against quasi-positive holier-than-thou representation, I'm going to do it. That's a fair way to put it. It's just not fun. It's not sexy.

It's always really nerve-racking to write into these more tricky parts of trans life and embodiment that other people might read and weaponize against us in this political moment.

MC: Cultural criticism has been such a hot topic of conversation with the state of media and our current political climate. What are your thoughts about that since you work in a lot of these spaces?

GB: It'll be interesting to see how people try to combat and evolve. A lot of people have migrated to Substack, but there are advantages and disadvantages to that. [The novelist] Brandon Taylor, when he read my book, was like, ’It doubles as an act of cultural criticism.’ And I hadn't thought of it like that. But I do think there's a way that criticism informs everything that I do in my way of writing, even when I'm writing more traditional books, and I love books that reference other books and think through other texts. There will always be criticism, but it has always been in crisis.

MC: Do you have any recommendations for favorite books or trans writers that you think people should check out?

GB: I always try to make a list that isn't just other trans writers, but I also think more people should be writing and reading trans literature as mainstream, because it is, and it has a lot to say about bodily autonomy at large, and also just fiction and life and the human condition. In my book, there are references to Nevada by Imogen Binnie, Stag Dance by Torrey Peters, and Manhunt by Gretchen Felker-Martin. I really love Wild Geese by Soula Emmanuel, which I think is under-read. I love Mrs. S by K. Patrick. I love Girlfriends by Emily Zhou. Lucy Sante is an incredible writer. Shola von Reinhold is a great writer. Harron Walker, Jamie Hood. There is an explosion of great writers, and people should read them and not just during some sort of quasi-weird trans readathon thing.

Kerensa Cadenas is a freelance journalist based in New York. She's previously held positions at Thrillist, The Cut, Entertainment Weekly, and Complex. Her byline can be found at publications like Vanity Fair, Indiewire, Rolling Stone, Vogue, NYLON Bustle, Vulture, and other outlets. She's always had a pop culture obsession from film, literature, television, music, and everything in between. On weekends you can find her going dancing, seeing comedy shows or films, or hanging out with her cat.