I Grew Up With a Stage Mom. I Can’t Help But Love Them

In an excerpt from her book 'One Bad Mother,' Ej Dickson explores why we love to hate momagers—and why they deserve a reassessment.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Marie Claire Daily

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Sent weekly on Saturday

Marie Claire Self Checkout

Exclusive access to expert shopping and styling advice from Nikki Ogunnaike, Marie Claire's editor-in-chief.

Once a week

Maire Claire Face Forward

Insider tips and recommendations for skin, hair, makeup, nails and more from Hannah Baxter, Marie Claire's beauty director.

Once a week

Livingetc

Your shortcut to the now and the next in contemporary home decoration, from designing a fashion-forward kitchen to decoding color schemes, and the latest interiors trends.

Delivered Daily

Homes & Gardens

The ultimate interior design resource from the world's leading experts - discover inspiring decorating ideas, color scheming know-how, garden inspiration and shopping expertise.

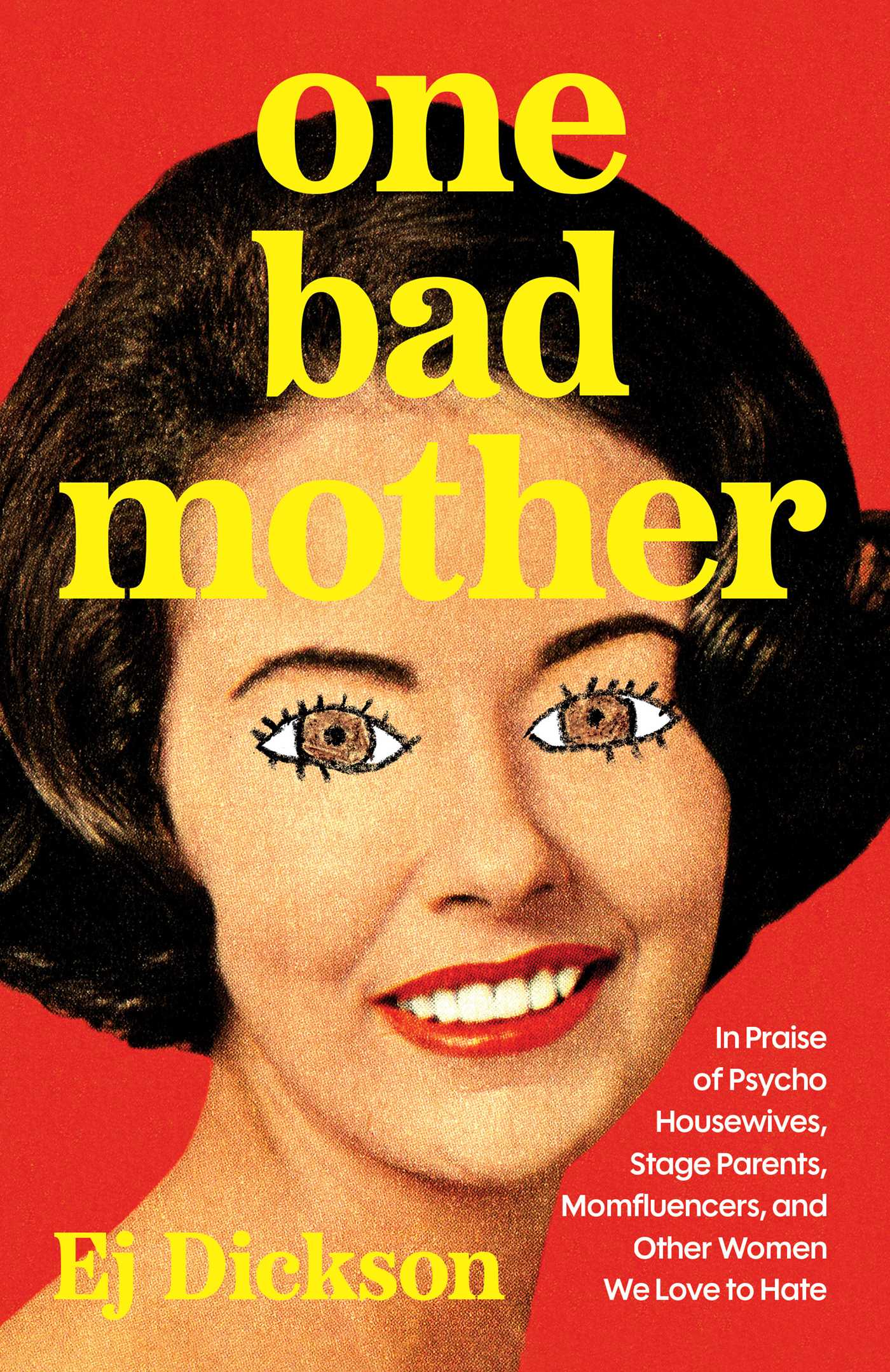

In her first book, One Bad Mother: In Praise of Psycho Housewives, Stage Parents, Momfluencers, and Other Women We Love to Hate, The Cut Senior Writer and culture journalist Ej Dickson explores our perceptions of what it means to be "a bad mom." Written through the lens of pop culture—diving into everything from classic sitcoms to Jennifer Coolidge's character in American Pie to the Kardashians—the book, out February 10, examines various archetypes and why they might deserve a reassessment.

The below excerpt from the chapter titled “'Give ’Em Love and What Does It Get Ya?," explores why we're often quick to judge stage moms—and why they hold a special place in Dickson's heart.

I have a soft spot for stage mothers, in part because, if you hew to a strictly technical definition of the term, my own mom (kind of) was one. I was a theater kid in every sense of the word: I did school plays, took acting and tap and voice lessons, and demanded attention wherever I went. When I was eight years old, my mom enrolled me in a kids’ acting workshop run by a former 1960s stage actress who gave lessons out of her Upper West Side studio. At the end of each semester, Monica May held a student showcase, and afterward, my mom told me she had gotten a call from an agent who had been in the audience who wanted to represent me. The agency was called—I shit you not—Lil Angels. Lil Angels was not particularly glamorous or prestigious. Its office was in Yonkers, about an hour from where we lived in New York, and when the agent sent me to a photographer to get headshots, he and my mom ended up styling me like a middle-aged stenographer from Staten Island named Linda. Still, I was excited, and I think my mom was, too. She’d harbored her own performing arts aspirations in her youth, and I think part of her felt like she would be depriving me of a valuable opportunity if I didn’t give it the old college try.

So, for about four to six months of my childhood, Lil Angels became a part of my life. Every two weeks or so, I’d be pulled out of school to schlep to auditions, where I’d be asked to read for things like toothpaste or laundry detergent ads, or, in one case, a production of the all-Black musical The Wiz,

before the casting director, who was always either an older woman with red-rimmed glasses or a young white gay man who smelled really good, politely thanked me for coming in and then I’d never hear from them again. And while I’m not sure exactly how my relationship with Lil Angels ended, I do remember that after a while, they just stopped calling.

My time as an aspiring child actor was relatively uneventful. At worst, it was a waste of time and money on my parents’ part (and hair spray on the part of the headshot photographer who tried to make me look like a woman who wore pantyhose and rode the tram to work). But even though I’m sure some people would sniff at my mom’s decision to sign me to a kiddie talent agency, I completely understand why she did it. I think she correctly assessed that even though there was a very small chance that I would be cast in anything, it was a chance that I would’ve regretted not taking. And yes, I’m sure there was a part of her that thought it was a chance she would’ve regretted not taking, too. For this reason, I’ve always been drawn to stage moms, from Momma Rose [from Gypsy] to “momager” Kris Jenner, long rumored to have leaked her daughter Kim Kardashian’s sex tape to further her career, to the eponymous housewives in Dance Moms, who are regularly depicted guzzling wine and slinging insults at each other while wearing an extraordinary amount of bedazzled denim.

It’s not so much that I relate to these women, or that I understand precisely why they’re so deeply invested in their children’s vaudeville or reality TV careers or, in the case of Dance Moms, whether they take first place in expressive jazz performance at nationals. It’s more that I sympathize with the general impulse to do whatever it takes to carve out the best life for your child, whatever that may look like for them. If one of the primary tenets of good parenting is wanting your child to have more opportunities than you did—and I think we can all agree that this is an admirable, if not always achievable, goal—then it stands to reason that if a parent senses exceptional talent or ability in a child, they will want to foster it.

Excerpted from One Bad Mother: In Praise of Psycho Housewives, Stage Parents, Momfluencers, and Other Women We Love to Hate. Copyright © 2026, Ej Dickson. Reproduced by permission of Simon Element, an imprint of Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Ej Dickson is a senior writer at New York magazine’s The Cut. She previously worked as a senior writer for Rolling Stone and her writing has also been published in The New York Times, The Washington Post, GQ, Elle, and many others. She lives with her family in Brooklyn, New York. Visit EjDickson.com for more information.