My Radical Break-Up With Romantic Love

I stopped chasing the kind of love we’re told to want—and it feels like I’ve unlocked a superpower.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Marie Claire Daily

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Sent weekly on Saturday

Marie Claire Self Checkout

Exclusive access to expert shopping and styling advice from Nikki Ogunnaike, Marie Claire's editor-in-chief.

Once a week

Maire Claire Face Forward

Insider tips and recommendations for skin, hair, makeup, nails and more from Hannah Baxter, Marie Claire's beauty director.

Once a week

Livingetc

Your shortcut to the now and the next in contemporary home decoration, from designing a fashion-forward kitchen to decoding color schemes, and the latest interiors trends.

Delivered Daily

Homes & Gardens

The ultimate interior design resource from the world's leading experts - discover inspiring decorating ideas, color scheming know-how, garden inspiration and shopping expertise.

The only romantic relationship I’ve ever had lasted exactly one week. It was my sophomore year of high school, and at the homecoming dance, I had my first-ever slow dance and my first kiss with a senior in my Spanish class. The kiss felt like nothing—just a closed-mouth brush of skin—but I rode on the high of being desired for the whole night and into the next day, when he asked me out over text. I felt suffocated. He was always texting, always wanting to hold hands, and I couldn’t match the intensity. I didn’t like him so much as the idea of him—and he deserved better than that. When I finally admitted how I felt to a friend, who promptly told him, we called it off—and I felt mostly relieved.

Since then, dating has never felt like a priority for me. I’ve always felt removed from the world of couplings and romantic relationships. It’s not like romance repulses me—I mainline romantic TV shows and K-dramas, and root for my favorite celebrity couples as much as the next fangirl—but I’ve never understood why anyone would feel that they need to date or have a partner. I watch those scenes where the heroine is like, “I just have to be with this person,” and my brain instantly goes, or… you could just not.

Sometimes, when I’m giving a friend advice as they spiral over a bad relationship, I wonder if some part of my brain is on an “off” setting. Like maybe once I meet The One, a switch will flip and I’ll morph into someone who’d willingly apply to Love Is Blind and rearrange their whole life around someone else’s texting habits. (Respect to y’all. But that is not my path.)

Looking back on my most boy-crazy days, even then, I think what I longed for wasn’t a boyfriend—it was a kind of unconditional love I hadn’t yet learned to show myself. A decade later, I’ve built a life full of it. I have deep friendships, fulfilling work, a strong relationship with my family, and hobbies that energize me. I live a life full of love, just not including the red-heart, Hallmark variety. And that’s not a deficit—it’s a choice.

It took a lot of introspection to take pride in that, since it goes against everything I’ve seen and heard since I was born. From the moment we arrive on this earth, people are taught that a romantic partner is all you need—the ultimate goal of life. Everything around us—from tax codes to Disney movies—tells us that finding “the one” is not just desirable, but necessary.

I’m lucky that my mom never pressured me to settle down; she only ever cared that I was fulfilled. But even without the grandkid nudges, society makes singleness feel like a waiting room for real life. Girls are taught that happily-ever-after is synonymous with married with children. That if a boy is mean, it must mean he likes you. That being chosen is the greatest validation of all.

I don’t need to chase after romantic love to seek fulfillment. I’m already surrounded by love. I give it freely. I receive it daily.

The first time someone questioned whether I was asexual, I rejected it. I was 21, living in Brooklyn with a roommate who was always swiping and dating. One day, after telling me about her latest romantic conquest, she asked why I didn’t date or hook up. When I said I just didn’t really care to, she asked if I might be asexual. I was immediately defensive. I ranted to friends later: How dare she say that? But what I really meant was, What if she’s right—and I’m broken?

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

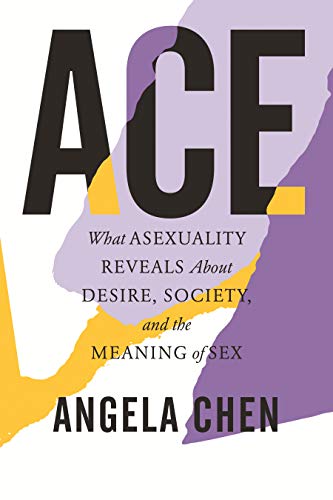

Years later, I finally picked up Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex by Angela Chen. It had been sitting on my bookshelf, taunting me, for three years. When I finally read it, everything clicked. I fell down the rabbit hole—not just of asexuality, but of aromanticism, the experience of feeling little or no romantic attraction.

That’s when I started to understand that I fall on the aromantic spectrum. I currently identify as demisexual and grayromantic, which means I only experience romantic attraction in rare, specific circumstances—far less frequently than someone who is alloromantic. I also came across a word that explained so much of my unease: amatonormativity. Coined by philosopher Elizabeth Brake, it’s the assumption that everyone wants a romantic, monogamous partnership, and that any life without it is incomplete.

Seriously, try to name ten shows or movies that don’t include romance whatsoever. Even daily interactions reinforce it. Try buying a car or booking a plumber without being asked, “Does your husband know about this?” Ask someone not to comment on your love life and it’s treated like asking them not to breathe. Why is “wife and mother” still framed as the natural endpoint of womanhood?

Asexual and aromantic flags at a Pride March in Paris.

There’s a reason for that. Romantic coupling, especially heterosexual marriage, is financially incentivized. Couples get to share the cost of living. Recent declining fertility rates in both the U.S. and worldwide have spurred governments to offer perks for procreation, but even before that, financial and social advantages for married couples have always been embedded into American life, from tax breaks to easier loans.

While couples get to share all the household costs that can be exorbitantly expensive for solo living, solo renters pay what’s known as the “singles tax”—an average of $14,000 more per year just for living alone in cities like New York. Even airlines are charging solo travelers more. And that’s before you factor in the social messaging that being alone is inherently sad. That anyone without a partner must be searching for one.

It’s funny that I was first confronted with my difference in 2016, when we were just on the precipice of a rise in conservatism that demonizes anyone who doesn’t fit into the hetero lifestyle, depending on who they are or who they love or what type of love they feel.

In the years since, I’ve had to reckon with every way I am marginalized: as woman, as Black, as fat, as queer. In a way it has been liberating: I’ve always felt that something was wrong with me because I don’t fit into what society wants me to be. I am bigger than what the bigots can imagine, and I don’t have to follow their script.

For the past year, I’ve been building my life outside of “should”—and it has made me feel like Wonder Woman. Not all the time; if you’ve read my work carefully, you’ll know that I still spiral plenty. But I’m no longer waiting for a mythical someone to make my life whole. Sure, since I fall on the “little” side of “little to no romantic attraction,” it could happen one day, but I don’t need to chase after romantic love to seek fulfillment. I’m already surrounded by love. I give it freely. I receive it daily.

There’s a radical power in choosing your people. It’s the one source of power I don’t overthink (mostly because I am entirely too crowd-anxious to start a cult). In showing up for your chosen family, day after day, without the promise of a wedding or shared lease. In building a community rooted in communication, not convention. I love that I put the energy into showing my mom the appreciation she deserves, and that I work to sustain friendships even when the people I love most live hundreds of miles from me.

I’m excited for the future—the queerplatonic partnerships I’ll build, the friendships I’ll deepen. To break out of my quiet-gay comfort zone and meet new people who think the same way, to form deep relationships that thrive on shutting out norms and shoulds. And I love that every time I say no to a system that insists I should want more, I’m saying yes to myself.

After all, who else can I be?

Quinci LeGardye is a Culture Writer at Marie Claire. She currently lives in her hometown of Los Angeles after periods living in NYC and Albuquerque, where she earned a Bachelor’s degree in English and Psychology from The University of New Mexico. In 2021, she joined Marie Claire as a contributor, becoming a full-time writer for the brand in 2024. She contributes day-to-day-content covering television, movies, books, and pop culture in general. She has also written features, profiles, recaps, personal essays, and cultural criticism for outlets including Harper’s Bazaar, Elle, HuffPost, Teen Vogue, Vulture, The A.V. Club, Catapult, and others. When she isn't writing or checking Twitter way too often, you can find her watching the latest K-drama, or giving a concert performance in her car.