Sorry, Consuming Trauma Porn Is Not Allyship

Why aren’t Black victims afforded the same dignity in death as white victims?

“You’re being ignored. I’m not letting you bring me down today,” I said to a white staff member at the psychiatric hospital I’d been at for a month and a half. He’d made it apparent he didn’t like me from the day I was admitted. “What did you say to me?” he exclaimed, positioning his body to block my path. I rolled my eyes and attempted to walk around him. Before I could take two full steps, he slammed my head into the wall so hard I nearly passed out. He then swept my leg out from under me with his foot, tackling me to the ground.

I started screaming for him to get off of me. He lied to a coworker, saying I attacked him, and ordered her to issue a “Code 100,” dispatching several other staff members to help restrain me. He placed his right forearm on the back of my neck, pouring his full body weight onto my 13-year-old self. I tried to fight him off.

“I can’t breathe,” I managed to shriek from underneath the dog-pile of staff members helping him hold me down.

No one was listening.

Two weeks ago I found myself sitting in front of my computer with tears running down my face. I studied a video of Derek Chauvin pinning his knee firmly into George Floyd’s neck, as terror filled Floyd’s eyes. It was a moment that was all too familiar. The post’s caption read, “Final words: I can’t breathe.” The video dredged up unbearable memories and opened old wounds in me.

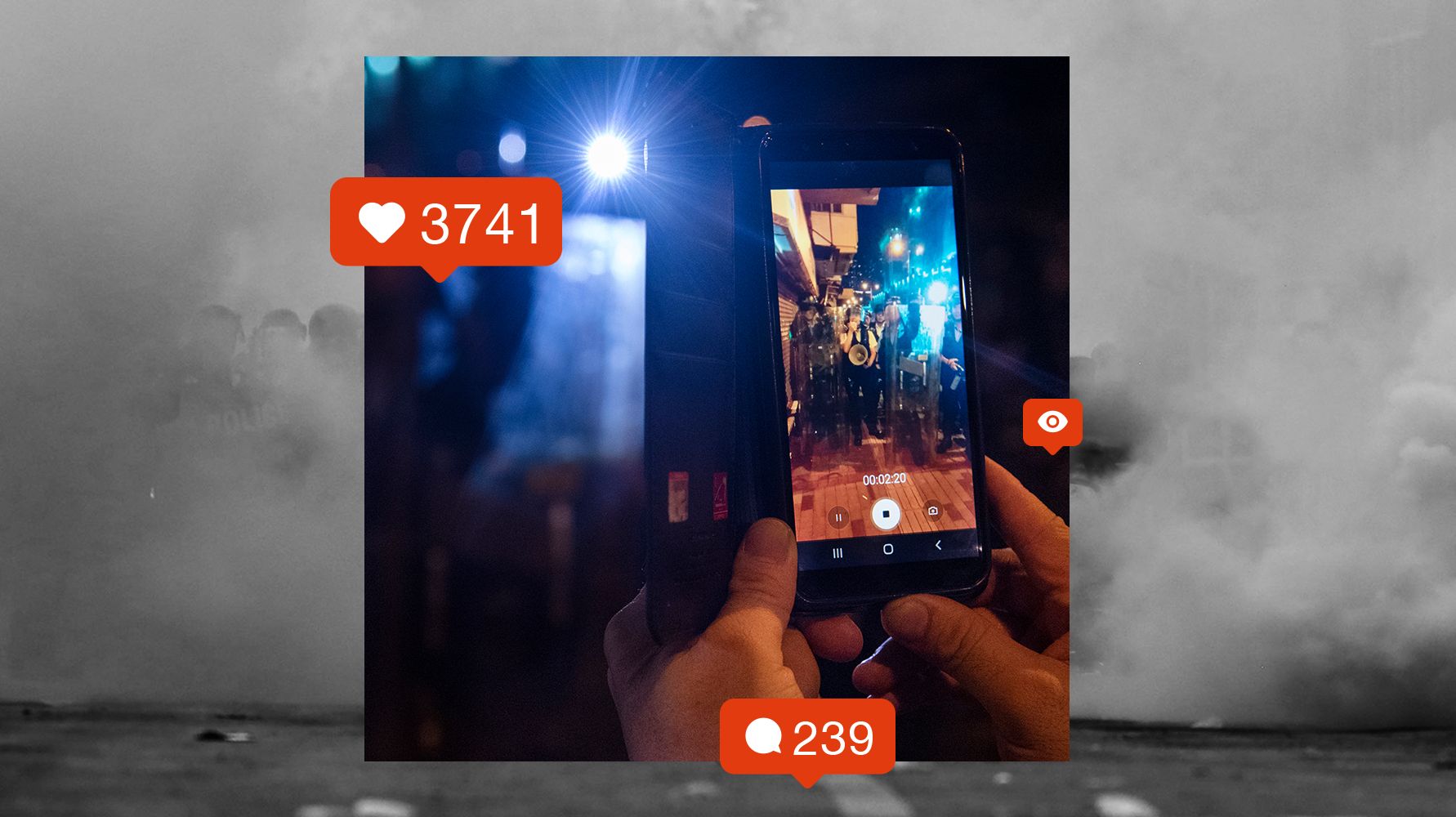

After seeing the footage I was overcome by inconsolable frustration. Not only was I angry I’d been caught off-guard (the video played automatically when I scrolled past it), I was also upset that thousands of white Americans—whose unwillingness to help dismantle systemic racism made George Floyd vulnerable to police brutality—were now given front row seats to voyeuristically consume his pain.

America has always had an addiction to Black death and trauma porn, and it’s about time we talked about it.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

The consumption of Black pain is as American as apple pie—pies that were once brought to lynching barbecues in the early 1900s. At the time, white mobs would concoct dubious accusations toward Black men, eventually deciding to lynch them. Weeks beforehand, the accusers would promote "the event" in local papers, drawing families from all over to bear witness. Attendees would share meals and socialize and kids would play and eat ice cream sundaes while the victim was tortured for hours. When they'd lynch him, onlookers would cheer. Afterward, they would burn the body; families would take pictures next to it, using the photos for postcards. Once they’d dismembered the body, attendees were permitted to take home a piece of flesh, bone, or rope from the lynching as a souvenir.

But today, society takes part in a modern-day form of lynching: sharing trauma porn. The method may have changed, but the motivation is still the same. The extreme discomfort you may have felt while reading the details of last century's lynchings is similar to the discomfort many Black people feel when viral videos of us being publicly murdered are shared all over the internet. Lynching was designed to terrorize, humiliate, and inflict pain and suffering on Black bodies; police brutality and vigilante murders are an extension of that tradition.

The purpose of publicly torturing Black bodies, then and now, is to deter Black Americans from challenging white supremacy. And by re-sharing, liking, or posting videos of Black people being murdered, you’re inadvertently helping to spread that message. When was the last time you saw a video of a white person being murdered on Instagram? There have been several mass shootings recently, yet none of the photos or videos of the victims in their dying moments go viral. Why? Because unlike Black victims, white people are afforded dignity in death—most of the videos or images of death we see in the media or on social media are typically of Black and Brown people.

As human beings, death places us at our peak of vulnerability; the deceased, no matter their skin color, deserve privacy, dignity, and respect in those final moments.

You may wonder: Where’s the harm in sharing graphic videos of Black death if those videos are meant to spark public outrage and seek justice? The viral video of George Floyd being murdered led to multiple arrests which, for many, felt like justice. But even when an officer or vigilante is charged or convicted for murdering Black people, it’s only half of a victory. Arresting an officer without dismantling the system that molded him is like arresting the gun, not the shooter. That officer or vigilante that murdered a Black person wasn’t an isolated case, but, in fact, part of a larger, systemic problem. White supremacy is the ultimate culprit, and it walks free every single time.

Perhaps, as a white ally you sighed with relief when the officer responsible for George Floyd’s death was arrested. Maybe you thought your work here was done, only it isn't. Unless you’re pulling up systemic anti-Blackness by the root, you’re merely placing a bandaid over a bullet wound.

Sharing images of Black death on social media won’t save Black lives. Instead of eradicating our murders, it normalizes them. Year after year, life after life, innocent Black blood is spilled, and yet the system responsible is left intact.

The fact that you’ve made it this far proves you’re ready to jump into action. Here are eight ways you can help destabilize white supremacy in America, instead of posting that video to Instagram:

- Commit yourself to anti-racist work. Read articles and books by Black authors on structural and systemic racism. (There are also some really good books from white authors on their processes of examining their own inherent racism.) But be cognizant of supporting Black authors, book stores, and businesses to build them up economically.

- Support the families of the slain and donate to memorial funds. You can also donate to organizations helping fight for racial justice.

- Avoid amplification without action. Instead of sharing those unsettling videos or images of racial injustices being committed toward Black people to your whole feed, send it directly to a non-Black friend, family member, or loved one and use that moment as an opportunity to start a conversation. Share some of the information you’ve learned through your anti-racist work and make a plan on how you can collectively work together to dismantle systemic racism. Working with others promotes consistency and accountability.

- Put your body on the line for racial justice. Show up to rallies and protests to protect Black people from police harassment. (Police are typically less likely to assault or arrest a non-Black protester than someone Black.) If you cannot attend mass gatherings because of COVID-19 quarantines, disabilities, or other personal health issues, consider donating to an organization that bails protestors out of jail, or offer yourself up to be an emergency contact if someone needs one.

- Call your elected official’s offices, local police precincts, and attend city council meetings to drive accountability. Sign petitions and push for policies that center on racial justice.

- Check on the Black people in your life and center their emotional needs. You may think expressing your outrage on social media over Black murders is a show of solidarity, but, for us, it's simply a reminder that we’re constantly doubted over the egregious realities we suffer at the hands of white supremacy. Offer to drop money in a Black person’s cash app or Venmo for a self-care day.

- Believe, listen to, and trust Black people. Avoid gaslighting us about our own experiences. Life is exhausting enough for Black people without having to debate our truths or prove our trauma is real.

- Intervene on behalf of Black people on social media. Social media is often a brutal space. Comment sections are landmines filled with ignorant commentary and overtly racist remarks. Don’t just sit on the sidelines. Intervene. It makes us feel supported and shows you’re willing to confront White supremacy head on instead of infantilizing or making excuses for it.

For several more ways you can actively work toward racial justice, check this out.

Going forward, whenever you come across content that contains Black pain, suffering, or death, be sure to exercise careful consideration as to whether or not you should share it.

Questions that may help you make that decision are:

“What is my intention in sharing this?”

“How could sharing this help and how could it hurt?”

“Will sharing this contribute to a social ecology that produces these types of outcomes for Black people?”

And, most importantly: “Other than sharing this content to spread awareness, what am I willing to do offline to help break the vicious cycle of anti-Black violence that destroys Black lives?”

Read More About Racism & Allyship

Ashlee Marie Preston is an award-winning Media Personality, Cultural Commentator, Social Impact Strategist, Political Analyst, & Civil Rights Activist. She is also the founder of “You Are Essential,” an initiative that funds grassroots organizations serving vulnerable communities.