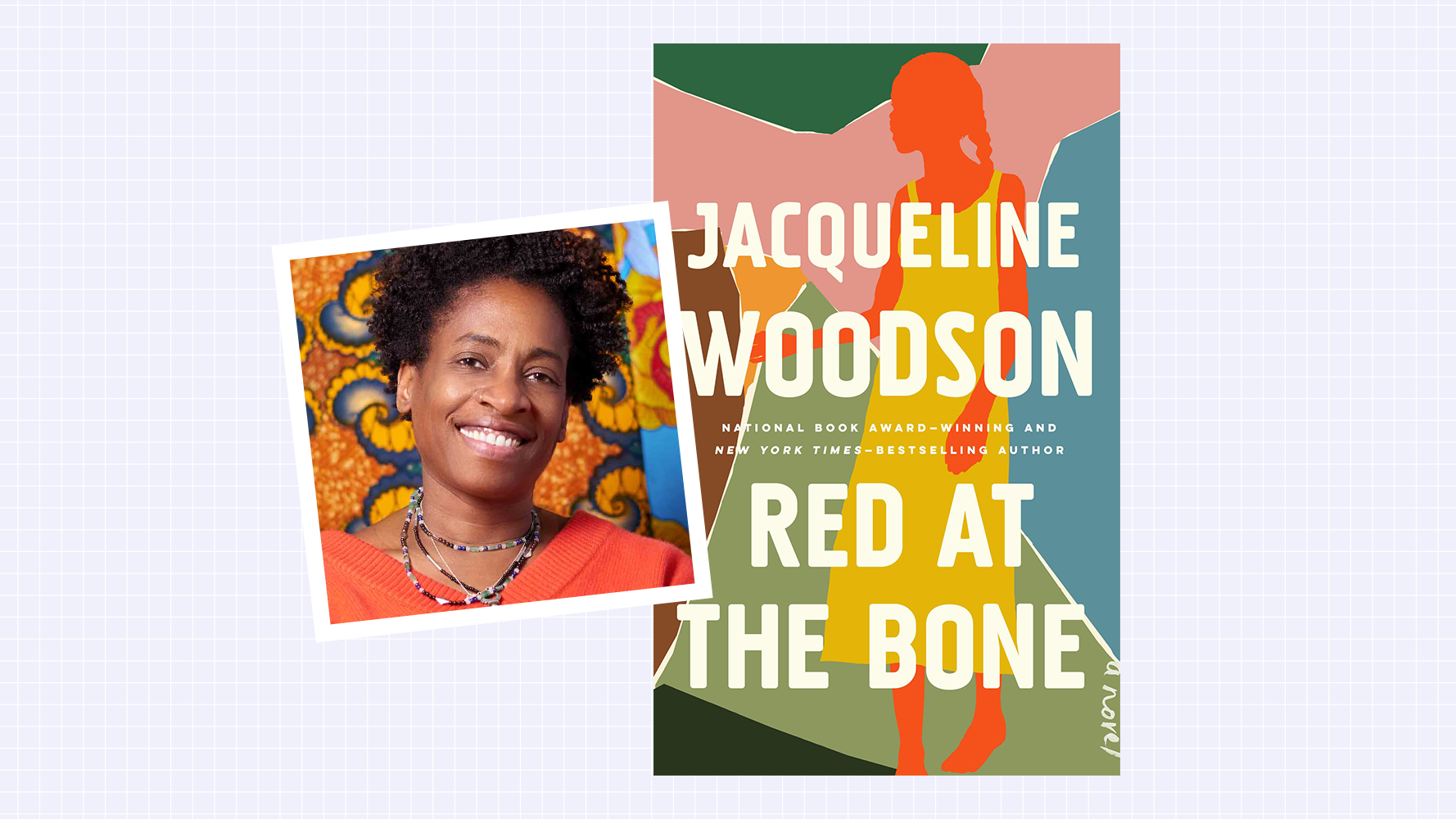

Jacqueline Woodson's 'Red At The Bone' Takes On Race, Sexuality, and Class

It might be a slim read, but Red At The Bone packs a punch.

“But that afternoon there was an orchestra playing,” begins Jacqueline Woodson's newest novel, Red at the Bone, out September 17. Traversing time and space, Red at the Bone tells the story of a Brooklyn family rocked by their teenage daughter Iris’s pregnancy. Through Iris, her parents Po’ Boy and Sabe, her ex-boyfriend Aubrey, and their daughter Melody, Woodson, 56, explores each character’s experience navigating class, gender, and sexuality. Its events span 100 years, starting with the 1921 Greenwood Massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where white residents attacked black business owners.

But that morning, there was construction in Park Slope. “I’m going to close the door,” Woodson says, concerned the noise outside will interfere with the tape recorder. “Hence, the ever-changing Brooklyn.” We’re sitting at the marble island in her kitchen, and the grating of a jackhammer wanders in through the back door. When she and her partner, physician Juliet Widoff, moved into the brownstone, they replaced the back wall with paned glass because Woodson prefers light in the kitchen; it’s where she does most of her writing. The prolific, National Book Award–winning author has released a book nearly every year since 1990 and won almost as many awards. Red at the Bone may earn her some more.

Woodson at The Lab School Of Washington 32nd Anniversary Gala Fundraiser.

Marie Claire: What inspired Red at the Bone?

Jacqueline Woodson: The the first thing I was thinking about was the Tulsa Massacres that occurred in the 1920s, and so many instances where a black middle class was basically annihilated. I always start every book with this idea of 'What if?': 'What if I created a family where there was a class divide? What would that look like? How would they have gotten their money? How would they have held onto their money and what did the class divide mean in the context of this story?' From there it just kind of organically grew into Melody and Po' Boy and Aubrey's story.

MC: Why did you set it in Brooklyn?

JW: I think the reason that so much of my work is set here is because it's ever-changing. I could write a story that takes place in Brooklyn in the 1990s and it could be a completely different story in the 2000s. And so, something happening in Brooklyn in the ‘70s is no longer happening in the '90s. My Brooklyn as a child is very different than my daughter's Brooklyn as a child, but we're still hardcore Brooklynites and have some similarities to our experiences because of this borough.

MC: What do you still notice about Brooklyn every day?

JW: In this neighborhood, I'm always completely blown away by how absolutely white it’s become, whereas it was much more racially diverse back in the eighties and nineties. So even though I see it every day, I'm always like, 'Wow, I just walked three blocks and didn't see another person of color,' you know? So that kind of thing captures my attention. And I love the light here.

MC: It’s interesting that you bring up light, because Red at the Bone’s cover is sort of a mosaic design, like how the same story is refracted through all these different points of view.

JW: I always find that compelling as a writer. Two people have the same experience and it's completely different in their eyes. I think about when I was writing Brown Girl Dreaming and how the story that my younger brother would have told was very different than mine, was very different from my older brother’s, and that's because what I understood as a 9-year-old, my 13-year-old brother saw differently and my 6-year-old brother saw differently.

MC: As you travel to different parts of the country as the Library of Congress’s National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, what feedback are you hearing about how schools are teaching progressive books, given the current political climate?

JW: I feel like so much of my work in this political climate has been trying to get people comfortable with talking about race and economic class and gender and sexuality and all of these quote-unquote, taboo subjects, so that they can feel safer. What I’ve found is, the teachers are sometimes more afraid than the young people to talk about this stuff. I find that a lot of white teachers tend to have a hard time talking about race, and kids are hungry to talk about it because it's such a racially-charged time. What I try to do is use the books as a kind of jumping-off point for talking about stuff. A lot of times, white families don't talk about race at home, so if the kids aren’t learning how to talk about it in school, and not learning how to talk about it at home, they don't know how to talk about it. Meanwhile, kids of color are having all these conversations about everything from why they can't play with guns, to why their parents are being taken away.

It’s heartbreaking that people don't always know that books can be a tool and you don't have to be afraid. We're always going to say the wrong thing, you know? The wrong thing shouldn't be something that keeps us silent. As Audre Lorde said, "Our silence is not going to protect us."

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

MC: At one point, Iris says, "I don't want to label my sexuality. I just want to be with Jam." How did you decide to have her not identify with a sexual orientation?

JW: I think that, you know, in the nineties there was so much like—"Are you gay? Are you bi? Are you lesbian?" You know, we didn't even really have a trans narrative; it wasn't as articulated it as it is now. Now we live in a culture where young people—bless their hearts, I love them so much—are just fluid, right? I wanted her to be kind of that forward thinker.

MC: In recent years, there’s been a push for more diversity in publishing. What are some of the biggest misconceptions about diversity in publishing or lack thereof?

JW: I think people are seeing a lot more books by people who haven't historically been part of mainstream publishing. And that's a good thing. In children's books, we're doing really well. One of the misconceptions [about more diversity in publishing] is that it just means publishing more books [by people of color]. But what we want is more people of color in editorial positions and publicity, and making the decisions. I think publishers understand what it means to have a very diverse house, too. It means you don't have to hire sensitivity readers. You don't make dumb mistakes about what you publish. And everyone gets represented or you represent as many people as you can.

People think #OwnVoices [a hashtag on Twitter that promotes the works of diverse writers] means books that only certain people can read. And what white folks don't realize is for a long time, everyone had to read books about whiteness and try to find some aspect of themselves inside those narratives. And now what's being asked is that people do that with all books: books by indigenous people, books by queer people, books by people of color, across the lines.

A version of this story appears in the September issue of Marie Claire.

RELATED STORIES