Why I Left My Own Billion-Dollar Brand

After years spent telling women they’re beautiful as they are, I couldn’t back skin-whitening and contouring products, Bobbi Brown writes.

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Marie Claire Daily

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Sent weekly on Saturday

Marie Claire Self Checkout

Exclusive access to expert shopping and styling advice from Nikki Ogunnaike, Marie Claire's editor-in-chief.

Once a week

Maire Claire Face Forward

Insider tips and recommendations for skin, hair, makeup, nails and more from Hannah Baxter, Marie Claire's beauty director.

Once a week

Livingetc

Your shortcut to the now and the next in contemporary home decoration, from designing a fashion-forward kitchen to decoding color schemes, and the latest interiors trends.

Delivered Daily

Homes & Gardens

The ultimate interior design resource from the world's leading experts - discover inspiring decorating ideas, color scheming know-how, garden inspiration and shopping expertise.

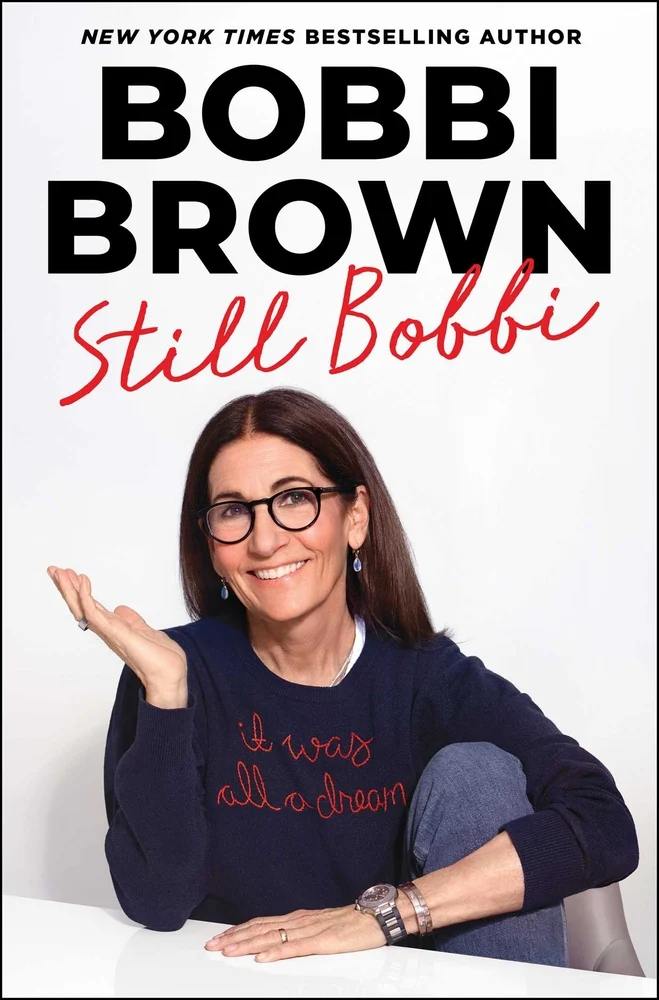

In her memoir, Still Bobbi, bestselling author, makeup artist, and founder of her eponymous beauty brand and Jones Road Beauty, Bobbi Brown reflects on how she embraced her own potential to become a beauty industry titan while raising a family. The excerpt below from Still Bobbi, out September 23, reflects on the challenges she faced in her final years at Bobbi Brown Cosmetics, before the parent company Estée Lauder asked her to step down from her role as Chief Creative Officer in 2016.

Everything was great...until it wasn’t. It took me a while to notice things were changing. My beloved magazines were struggling to survive. The editors, photographers, and magazines I loved were being elbowed out by Instagram influencers and YouTube tutorials. These changes I could live with. I had spent my life adapting.

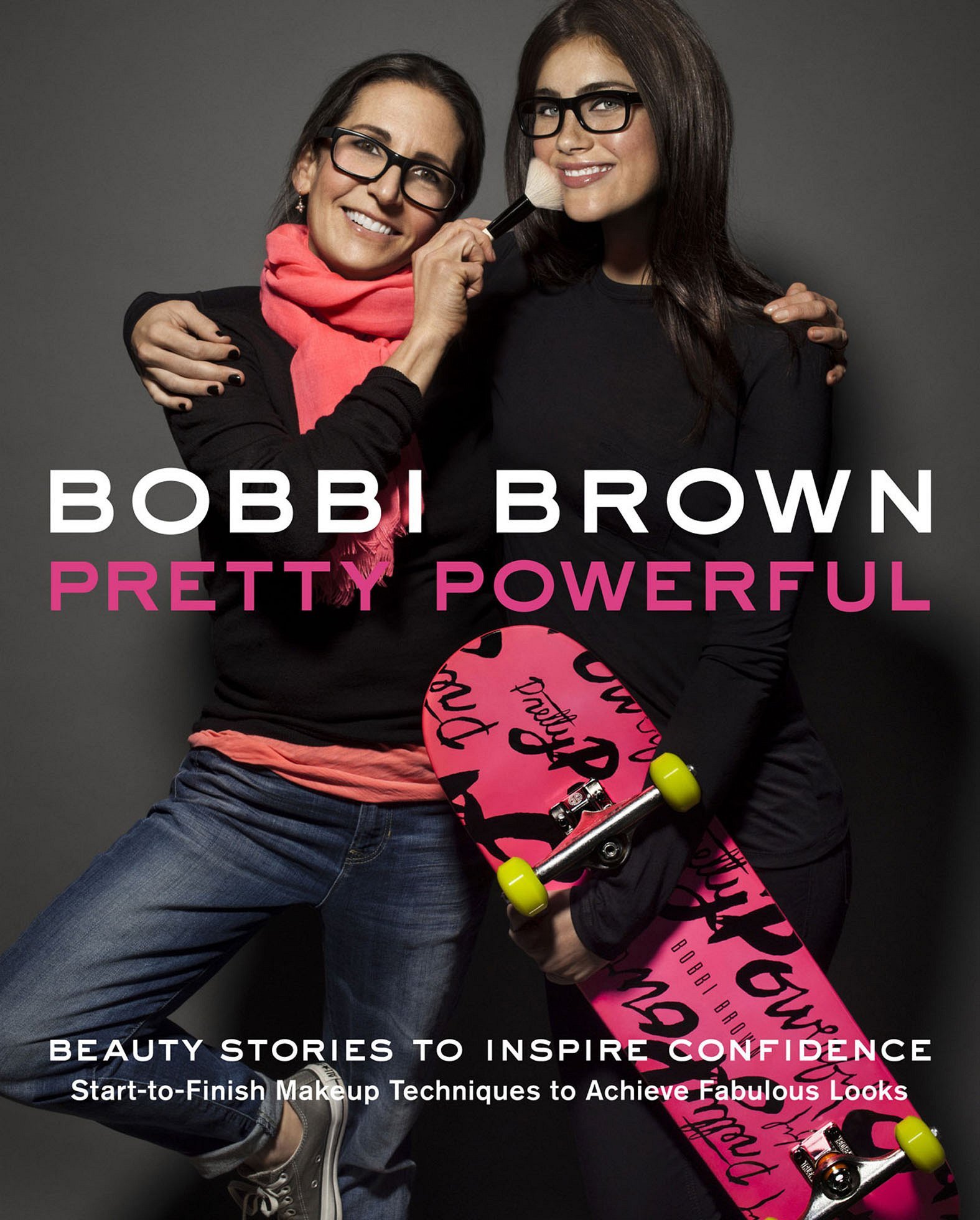

I had a more difficult time with changes internally. In 2009, the corp. hired a new CEO with a different style than his predecessors. Things changed slowly at first, but by the time I released my book Pretty Powerful in 2012, I definitely felt something wasn’t right. The book was an encouragement for women to start with who you are and just be you as your best self. I interviewed dozens of real women, celebrities, and athletes about what beauty means to them, and then showed, step by step, how to achieve certain looks. In my mind, the book was a launching pad for the next global brand initiative, centered on this phrase to remind women that they could be pretty and powerful, that pretty is powerful, and that we are all pretty powerful. We ran into trouble with some global markets because “pretty powerful” is an American expression, so when they translated it, it didn’t have the same meaning. I argued to keep Pretty Powerful in English all over the world, and just educate our global teams about what it meant. I saw it as a slogan, like Nike’s Just Do It. But the company had hired a slew of new people in the foreign markets. They did not understand my vision, and no one on my team could convince them. They insisted on translating Pretty Powerful into different languages. The messaging got completely scrambled.

The head office didn’t seem to understand my vision. At one of our meetings, as I recall it, the new CEO declared: “Women don’t want to be pretty. Pretty is for girls. A woman wants to be beautiful.”

I begged to differ and said so.

My team couldn’t believe I had just challenged the CEO. He had put together a team, mostly men, who would never openly disagree with him in a meeting.

I used to look forward to these meetings. They were interesting and invigorating. I loved talking to the team, bouncing ideas back and forth, and working together to perfect our global messaging and marketing. But as the meetings got bigger and bigger, they became more formal and less invigorating for me.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

My team couldn’t believe I had just challenged the CEO. He had put together a team, mostly men, who would never openly disagree with him in a meeting.

The optimism was replaced with stress and fear. My team would endeavor for six months to prepare our presentations. Then we’d trudge up to the 42 floor of the GM Building to find 40 people sitting around a huge oval table with little microphones like at the UN. You had to press a red button to speak. Above our heads hung screens with associates conferencing from all around the world. Corporate employees sat on one side of the table and the brand team sat on the other side.

I never felt intimidated. I knew how to make and market makeup. I understood what women wanted, no matter where they came from. I wanted the brand I created to talk to people the way I would talk to people—truthfully and directly. I had an ideal customer in mind. I called her Mrs. Schwartz. Whenever we created something new, I’d ask my team, “When Mrs. Schwartz comes to the counter, will she understand this?”

But under these circumstances, my team struggled. I blame myself. I wanted Maureen [Case] to be paid more, and corporate said the only way to do that was to put her in charge of more brands. When this happened, I should have insisted on a structure that gave both her and us more support.

Maureen had a difficult time. She believed in our brand, but the stress and her bosses were pulling her apart. Veronika [Ullmer], our head of global PR, struggled too. She knew me well and understood what I wanted and didn’t want, but she had two corporate leaders and three brand presidents telling her what to do.

Things were starting to unravel, and I was frustrated and aggravated. We had 30 freestanding stores, along with a presence in 1000 other doors, spread across 60 countries. Add in new people in finance and wholesale, plus all the international regions that reported to regional heads, and it got too big and too complicated. It wasn’t relying on the strengths of a founder anymore and the original vision; it was built to homogenize all the brands. And I didn’t have Leonard [Lauder] in my corner saying, “Yes, Bobbi,” anymore; corporate powers had apparently shifted.

Leonard had been a brand builder. The new executives saw the numbers and trends pointing in a direction and wanted every brand to go in that direction. Instead of letting Bobbi Brown do what we did best, they tried to push us into whatever looked profitable and competitive at the moment.

At one meeting, I felt pressured to create a skin whitener because that was the top-selling product in Asia. But I had spent 20 years urging people to choose a foundation that matched their skin and not use makeup to lighten it. How would it look if I suddenly came out with a skin whitener?

“You don’t understand,” I was told. “This is a big category, and if we don’t make it, we’re not going to be competitive in Asia.”

I consider myself a reasonable person. I like to hear other people’s ideas. But I’m a fighter when I believe in something.

“Explain why people want whitening cream,” I said.

“They want to have a brighter complexion.”

“Then why don’t we make a brightening cream?” I said.

We compromised. We didn’t tell people their skin should be whiter, just that it could be brighter. I refused to market it as changing the color of your skin. It ended up being a fun challenge for me, but I’m sure the people at the top felt frustrated.

I consider myself a reasonable person. I like to hear other people’s ideas. But I’m a fighter when I believe in something.

Another time, one of the corporate guys showed me this thick concealer that was so not a Bobbi Brown product. I hated it. I said no way.

“Bobbi,” he said, “if you don’t approve this immediately, we’ll miss projections for the season.”

“Fine,” I said. “Miss it.”

It somehow got added to the launch calendar without my approval and was released anyway.

Perhaps the biggest fight came over contouring, which was having a resurgence among social-media influencers. At the time, everyone wanted to look like a doll, using the darkest foundation stick available to contour their face into oblivion. Corporate wanted me to cash in on the trend, but I refused. I just couldn’t do it. I never liked contouring. To me, it looks fake, and I don’t like fake. I was always teaching women they are beautiful as they are. They kept insisting. I kept refusing. The fight reached a ridiculous point when corporate suggested that I appear at Beautycon, a gathering of all the influencers and social media junkies who were into heavy makeup, baking, contouring—everything we weren’t. The PR team knew I’d hate it there, so they came to me with a compromise: What if we made a hologram of me, like they did with Tupac? Beautycon was so into the idea they offered to give us the main stage for free. That was the stupidest idea I had ever heard. It wasn’t me, it wasn’t authentic, and I refused to do it.

Meanwhile, Veronika would catch hell when I posted something on the brand’s Instagram. The higher-ups would demand: “Why is she posting pictures of her dogs or the salad she’s eating?” They wanted three posts on the next lipstick, and a contouring palette, and user-generated content from influencers, with everything planned out a month in advance. That’s not what I wanted and not what I believed in.

The more I said no to these terrible ideas, the more I noticed things happening without my consent. Around this time, I left a photo shoot and the creative director decided to style a wildly retouched, white, pasty model wearing a black leather glove and dark purple lipstick, grimacing into the camera. It didn’t look like beautiful skin and happy models. It looked like Elvira wearing bad makeup. Thankfully, the global teams hated it and I was able to stop it from seeing print.

I began to dread going to work. Most days I came home angry and vented to [my husband] Steven. “Why don’t you just leave?” he asked. But I couldn’t. This was my company. It had my name, my face, and my philosophy attached to it. It was the number one artist-created brand in the world, selling 220 million products per year. I kept thinking I could fix it. If I could just find the right people and say the right thing. If, if, if. I got through a week thinking it was going to get better. A week turned into a month, a month turned into a year, then two, then three, and I woke up one day and thought, What the hell happened?

Excerpted from STILL BOBBI. Copyright @ 2025 by Bobbi Brown. Reproduced by permission of Marysue Rucci Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved

Bobbi Brown is a beauty industry titan, world-renowned makeup artist, bestselling author, sought-after speaker, serial entrepreneur, and the founder of her eponymous beauty brand and Jones Road Beauty.