The Risky, Wild Fun of Launching a Literary Publication

How founders Anika Jade Levy and Nat Ruiz turned 'Forever Magazine' into every It girl's must-read.

The Cost of Starting Your Own Business talks to founders to get an honest look at what it really takes to create a company. Not just the financial, but the personal and emotional costs, too.

Like many people during the pandemic, writers Anika Jade Levy and Madeline Cash were craving community. The longtime friends had always been drawn to an earlier era—a time when writers were celebrities in their own right, with buzzing social circles built around books and ideas. In October 2020, they decided to create that space themselves, and organized an outdoor reading for emerging writers at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery.

The turnout was overwhelming—enough to get Levy and Cash barred from hosting future events at the landmark. Although the prospect of future readings there was laid to rest, they left inspired to create something else: Forever Magazine, an independent literary and art publication with a deliberately subversive, feminine point of view.

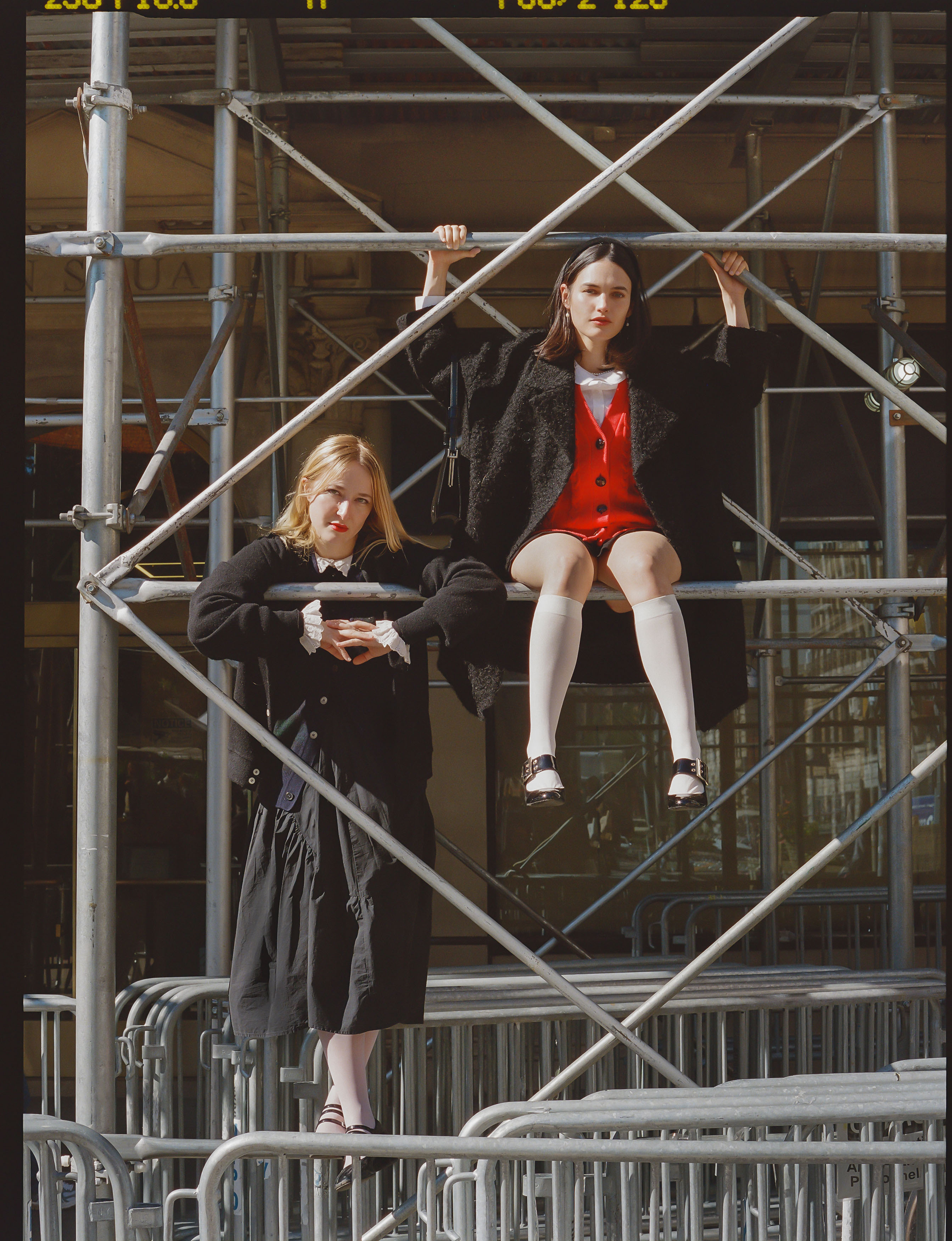

Forever Magazine founders Nat Ruiz (left) and Anika Jade Levy.

The pair brought on Nat Ruiz, Levy’s college friend and a full-time art director, and together envisioned the magazine as a way to revive the literary scenes in L.A. and New York. They also wanted to create space for emerging voices who often struggle to get published elsewhere, at a moment when universities were cutting funding for fiction programs and the Trump administration had slashed support for the arts.

What sets Forever Magazine apart is its refusal to separate “serious” literature from cultural spectacle, like the decision to publish prolific poet Eileen Myles and scammer-turned-socialite Anna Delvey in the same issue. For Ruiz, it was “a way that we could say to the world, ‘Only Forever would put these two people, these two artists, in one magazine.’” Five years in, the magazine continues to mix up-and-comers with established voices like Pure Colour author Sheila Heti and The Guest novelist Emma Cline.

How can you professionalize something that was built on friendship and not kill the magic? It's hard.

Nat Ruiz

While that approach has helped Forever Magazine grow from a 700-copy zine to print runs of more than 2,500 that sell out almost immediately—alongside a growing online audience and regularly sold-out events—the magazine has always been a deliberately passion-led operation. Funded largely out of pocket, Forever Magazine can currently afford to cover printing and shipping costs, but not contributor fees.

Today, it’s primarily a two-person effort: Cash, whose latest book Lost Lambs is out this month, stepped back after moving to London. Ruiz works full-time as an art director, while Levy balances freelance writing, adjunct teaching, and the recent publication of her debut novel Flat Earth. Over Zoom in November, not long after their eighth issue sold out, Levy and Ruiz reflected on five years of Forever Magazine, why the publication is “its own reward,” and what comes next.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Anika Levy: “Early on, Madeline got a piece of advice from Asher Penn, who runs Sex Magazine. He said, ‘In order to create a project that picks up momentum and becomes vital, you need to identify a cultural void and meet a need that's not being addressed.’ There was a need for what we were doing. A lot of the other underground lit magazines were really bro-y, and they also did not privilege aesthetics. Everybody was scared to be subversive or take risks. So, that cultural void was publishing people who were not going to be published anywhere else.”

Nat Ruiz: “We were early to the idea that consumers or readers can smell risk aversion, and being willing to take strong risks makes you immediately recognizable and compelling. We had nothing to lose because we had nothing.

The friendship came first—from me and Anika, Anika and Madeline, and then I became friends with Madeline. It became a project where the business model is friendship. I was totally down to put in time because the year before had been in lockdown. I just needed to do something that meant something with people who were passionate.”

Ruiz: “We all split the printing. Our first issue cost us about $700 to print. The first magazine is so thin because we could only afford to print on that paper quality, but we went all in, no hesitancy. I remember us being like, ‘Are we being too risky?’ and then we were like, ‘Fuck it, let’s do it.’

As demand has grown, printing costs have increased. Our most recent issue was around $3,000 to print, though that number can shift, since we often do reprints when issues sell out quickly. Shipping and fulfillment are additional out-of-pocket costs on top of that, but printing has been the biggest variable expense for us from issue to issue.

Circulation isn’t fixed and has scaled gradually in response to demand, but is also culled by our own ability to keep up with logistics and fulfillment. It’s always a bit nerve-wracking because we send out every order by hand ourselves and store the magazines in our apartments, so a higher print run risks trekking to the post office every day and living among boxes. We’ve been lucky to have a very loyal readership, and to date, every issue has sold out.”

My instinct is to hide that I'm white trash and came from dirt because that does not seem as fashionable in New York.

Anika Jade Levy

Levy: “The climate was very different five years ago. There was a lot about proving that you had working-class credentials. I think now we've moved to a climate where it's almost cooler to come from money. For myself, my instinct is to hide that I'm white trash and came from dirt because that does not seem as fashionable in New York. But our parents have not funded the magazine. My mom can’t even afford to buy the magazine [$27 with a shipping fee of about $5].

We pay for the printing and shipping ourselves; that’s it. We haven't bought ads or done paid social. In the absence of being able to pay people, what we can do is present their work very beautifully in a way that demands attention and serious engagement. But all of our growth and reach has been organic; it’s word of mouth, people come to an event, or we publish someone, and they share it. The people who are going to dismiss us are going to dismiss us, and there's no point trying to change their minds.”

Levy: “Smallness is something we've protected and nurtured to the extent that I send every single magazine out myself. Early on, when Madeline was doing the fulfillment, they were so frustrated with us at the Chinatown post office that she had to bake cookies for the postal workers. It's not that we are against expansion; it's that we really want to protect our point of view, and we're not going to sign away the keys to the castle.”

Ruiz: “We have talked a lot about what the future of Forever could look like, and we, of course, want it to grow. It would be amazing to actually make money doing it, so we can print more magazines and expand. We’ve had a lot of offers, but the thing we're trying to avoid is if an investor comes on board and they want to have a say in what we're publishing. If we were to ever grow, it would be on our own terms, and that is 100 percent.”

Levy: “We spend hundreds of hours on each issue. In terms of editorial, the work is disseminated throughout a calendar year or a season, where it will be a couple of hours every day. For Nat, it’s always an intense sprint."

'Forever' is almost like if we printed our group chat because we’re sharing ideas all day long.

Nat Ruiz

Ruiz: “When we're not in the sprint, it's a lot of collecting art—like, if I go to a show and I like something, or even being online. Forever is almost like if we printed our group chat because we’re sharing ideas all day long; one of the best parts of it is how we’re always thinking about it. But when I’m working on the issue, and there are deadlines in the last two or three months, it’s at least 30 hours per week. My weekends go away because I have a day job to be able to sustain life—we all do.”

Ruiz: “I took a hiatus from the magazine for eight months because I have an autoimmune disease, plus work was getting crazy, and I was moving to a new city. I have a pressure that is self-imposed; because this is a personal project, it is the most important thing…When I had to take a hiatus, it was when I felt my own pressure of, I don’t have the energy to put into the project. It was the right thing to do, and when I came back, I healed from that.

But there are many prices to pay. We’ve had arguments, and it’s painful when you have to fight with your best friends over a project that is meant to be because you’re good friends. But luckily, the friendship has always been number one, so we’ve always been able to resolve things.”

Levy: “Another thing that's been difficult is that I’m pretty ruthless editorially, and so much of both the indie and institutional literary scene runs on nepotism and favors. I have never once been willing to publish or accept work that I don't like because the only reason we're doing this is to create something beautiful. That means a lot of the time, not only rejecting friends' work, but often not even getting around to being able to read it. We get thousands and thousands of submissions. I wish I could read them, but again, we're doing this all for free. Socially, there's a cost to not being willing to publish your friends.”

Ruiz: “Our biggest challenges are definitely the success itself and logistics. We were not expecting to sell out the last issue in a week, for example. That means Annika has to ship all of them quickly, and it takes up so much time. How can you professionalize something that was built on friendship and not kill the magic? It's hard.”

Levy: “The reason that it continues to be compelling and shiny to people is our refusal to professionalize or our inability to professionalize. But the organizational aspects of executing every level of layout, print, and distribution ourselves are really hard. We've maybe made that needlessly difficult because we could raise our prices, we could pay for distribution…but it wouldn't be as special. It wouldn't have my handwriting on it. It wouldn't come in holographic bubble paper covered in Lisa Frank stickers. We'd be sacrificing a lot.”

Ruiz: “We’re already on the mood board: People are stealing the writers we’re publishing, the artists we’re publishing, even performers that come to our events blow up. It would be amazing if we got more credibility, but we’re not going to do it by stopping being who we are.”

Levy: “Seeing the meteoric rise of the artists and writers we’ve broken has also been such a privilege, and really creating physical spaces to celebrate that. It really does feel like we've addressed a cultural void.

Sadie Bell is the Senior Culture Editor at Marie Claire, where she edits, writes, and helps to ideate stories across movies, TV, books, music, and theater, from interviews with talent to pop culture features and trend stories. She has a passion for uplifting rising stars, and a special interest in cult-classic movies, emerging arts scenes, and music. She has over nine years of experience covering pop culture and her byline has appeared in Billboard, Interview Magazine, NYLON, PEOPLE, Rolling Stone, Thrillist and other outlets.