Books

Marie Claire's guide to books, with news, reviews and buying guides for the discerning reader.

-

Everything We Know About Netflix's Adaptation of 'Quicksilver,' One of the Hottest Romantasy Series on #BookTok

We can't wait for enemies-to-lovers Saeris and Kingfisher to grace our screens.

By Nicole Briese Published

-

25 Books By LGBTQ+ Authors You Need to Add to Your Reading List

You won't be able to put down these moving memoirs and touching romances.

By Bianca Rodriguez Published

-

11 Books to Read When Not Even an Aperol Spritz Can Fix Your Summertime Sadness

Feeling the summer bummer malaise? No problem.

By Liz Doupnik Published

-

Being Plus-Size on 'America's Next Top Model' Was Meant to Be My "Hook"

In an excerpt from her memoir 'You Wanna Be On Top?,' Sarah Hartshorne describes her time on the infamous show.

By Sarah Hartshorne Published

-

Now That We've Devoured 'Onyx Storm,' We're Rounding Up Everything We Know About the 'Fourth Wing' TV Show

Rebecca Yarros's bestselling romantasy series is getting the Prime Video series treatment.

By Quinci LeGardye Last updated

-

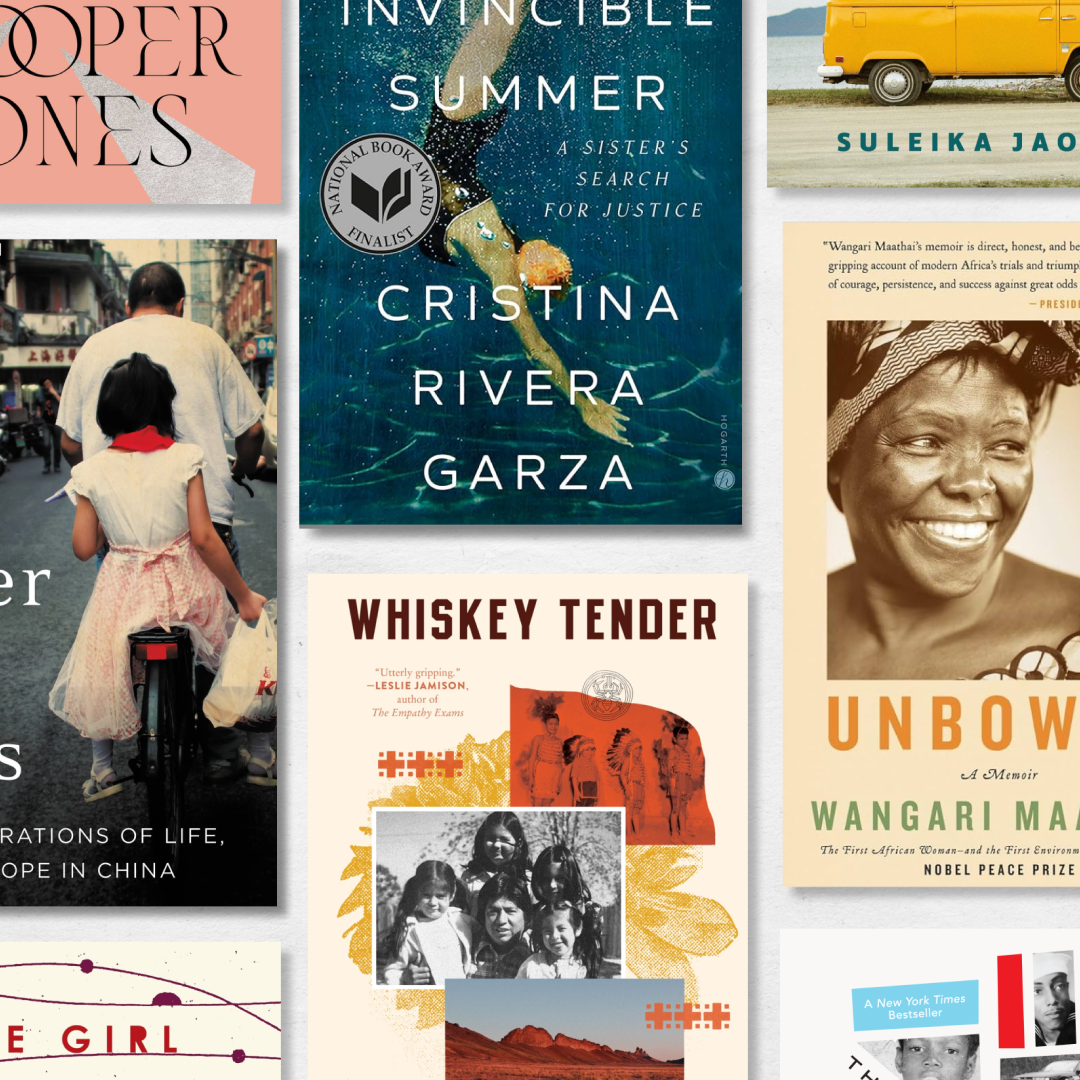

34 Fascinating Memoirs You Won't Be Able to Put Down

Make room on the nightstand.

By Alexis Jones Published

-

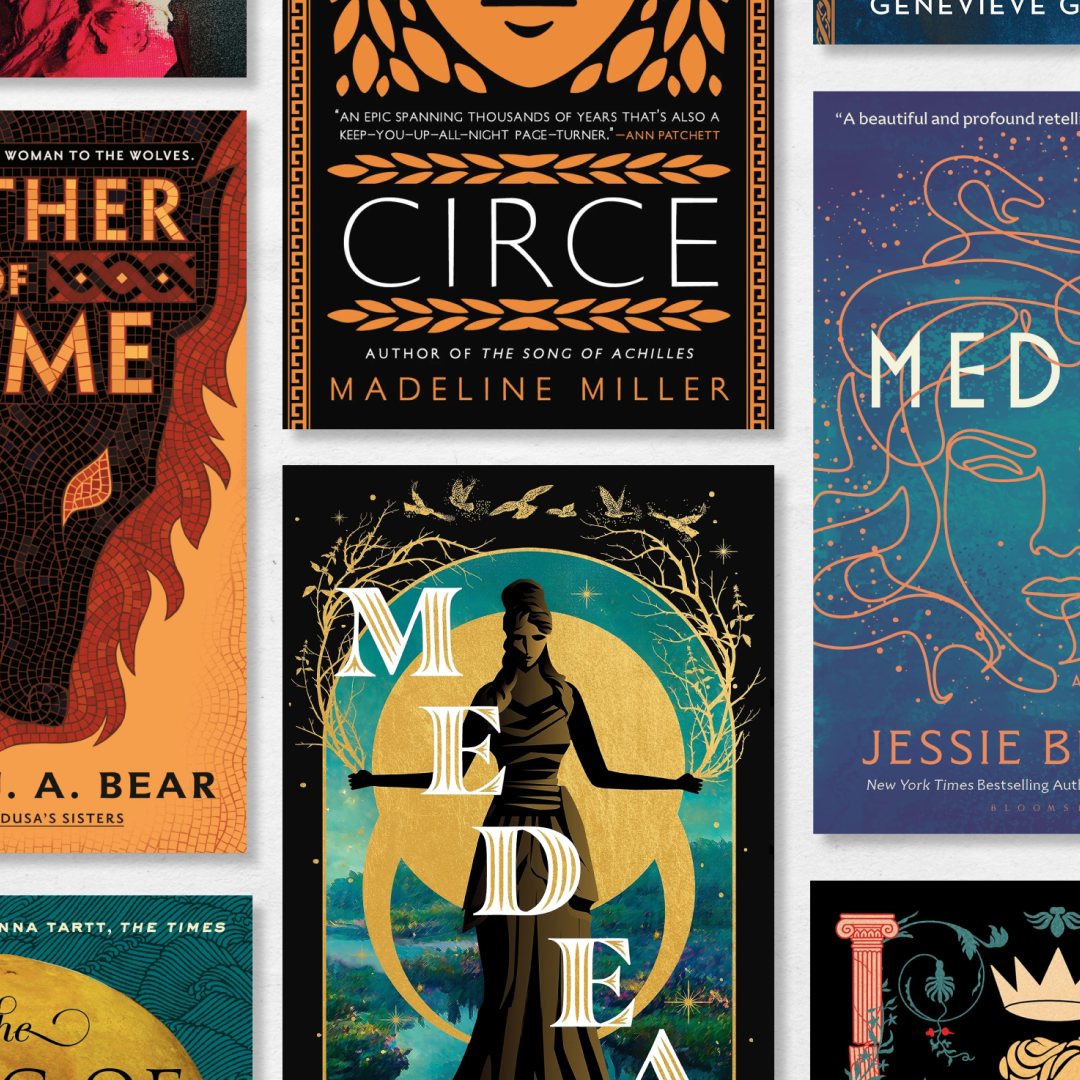

16 Books That Put a Modern Day Twist on Ancient Mythology

All the gods and goddesses you know and love, but with a scandalous or feminist twist.

By Nicole Briese Published

-

Elyce Arons Hopes You Remember Her Best Friend Kate Spade—and the Business They Built—As She Does

The 'We Might Just Make It After All' author reflects on the handbag empire's humble origins and her late business partner.

By Nicole Briese Published

-

2000s Nostalgia Is As Prevalent As Ever. But These Authors Aren't Sure Our Cultural Obsession Is for the Best

The 'Culture Creep,' 'Girl on Girl,' and 'Waiting for Britney Spears' writers discuss their new books and why we can't let Y2K go.

By Kerensa Cadenas Published

-

10 Must-Read Thrillers That'll Inspire You to "Be Gay, Do Crime" This Pride

These murder mystery books feature acts of queer resistance—and should absolutely be on your TBR stack.

By Andrea Bartz Published

-

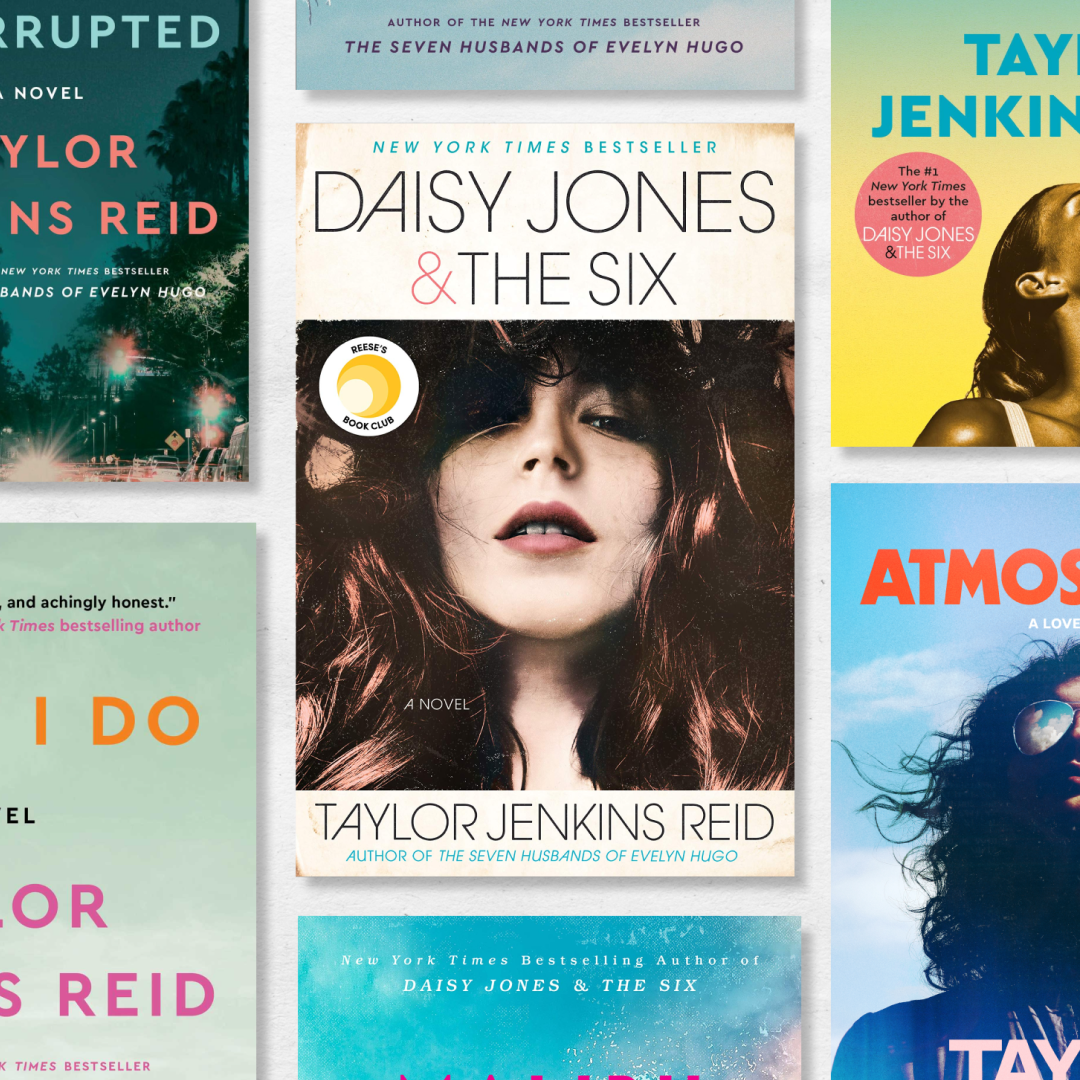

Every Taylor Jenkins Reid Book, Ranked—From 'Daisy Jones & the Six' to 'The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo'

Her latest novel, 'Atmosphere,' just hit shelves.

By Nicole Briese Last updated

-

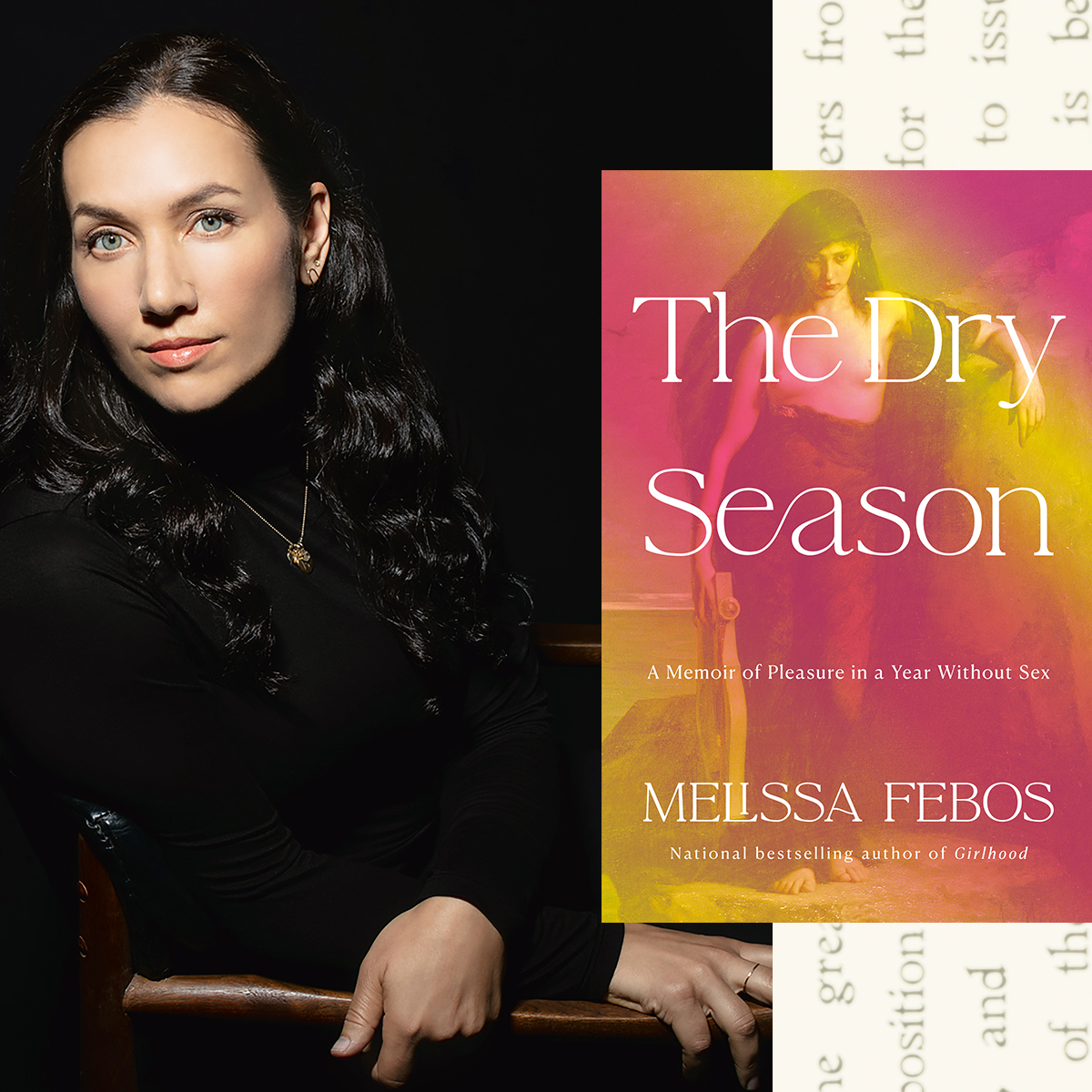

8 Divinely Erotic Books to Kick Off Your Hot Nun Summer

With her new memoir, 'The Dry Season,' out now, Melissa Febos shares the surprisingly sexy books she read during her year of intentional celibacy.

By Melissa Febos Published

-

We Ranked Every Book by Ali Hazelwood, Who Went From Scientist to Best-Selling Romance Novelist

Her novels are known for being set in the STEM world...and being very steamy.

By Nicole Briese Last updated

-

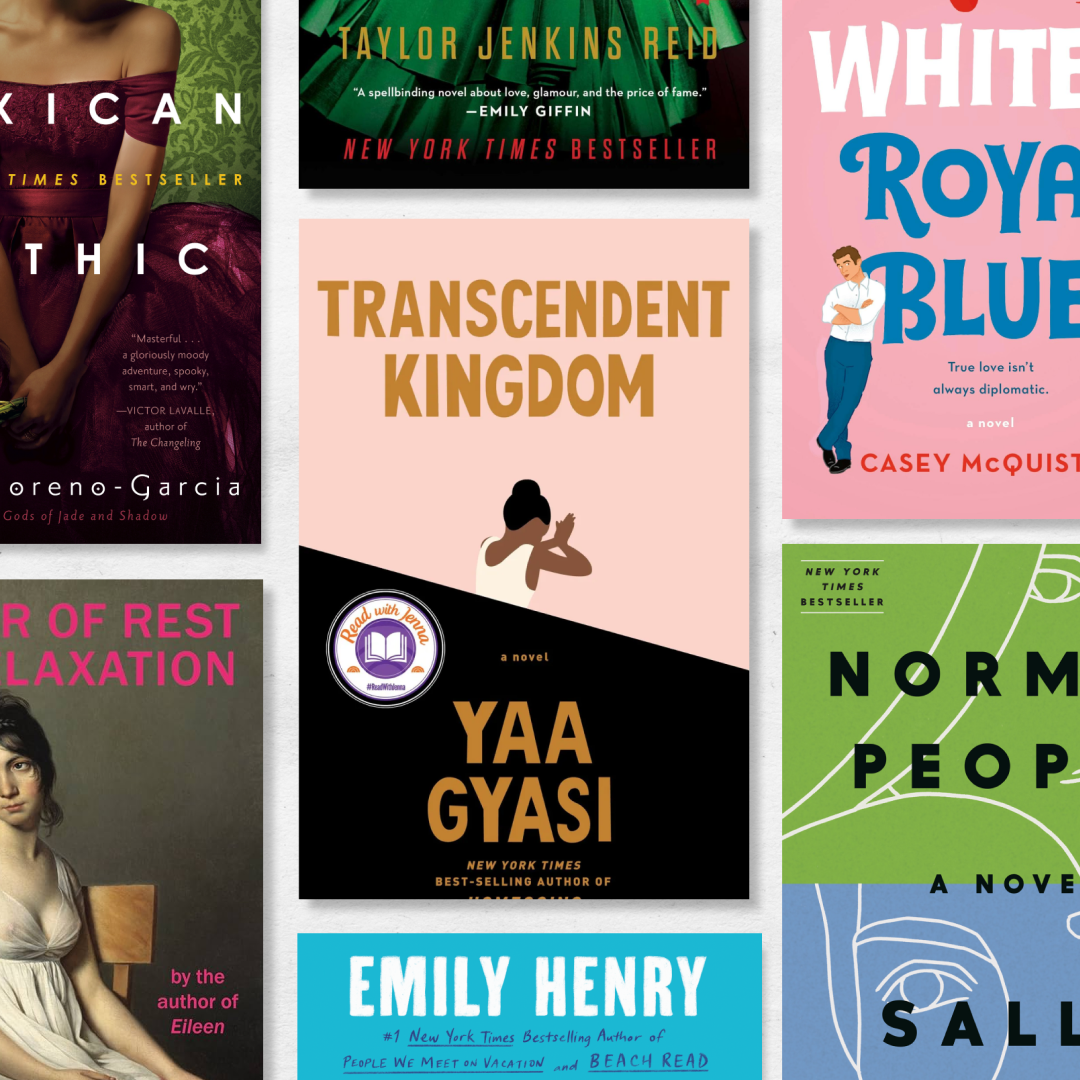

25 Books That Are Wildly Popular on TikTok—and Absolutely Worth Reading

BookTok is obsessed, and so are we.

By Brooke Knappenberger Last updated

-

Sarah J. Maas Has Been Dropping Hints About 'A Court of Thorns and Roses' Book 6. Here's What We Know

We're dying to read the next installment in the hit romantasy series.

By Nicole Briese Published

-

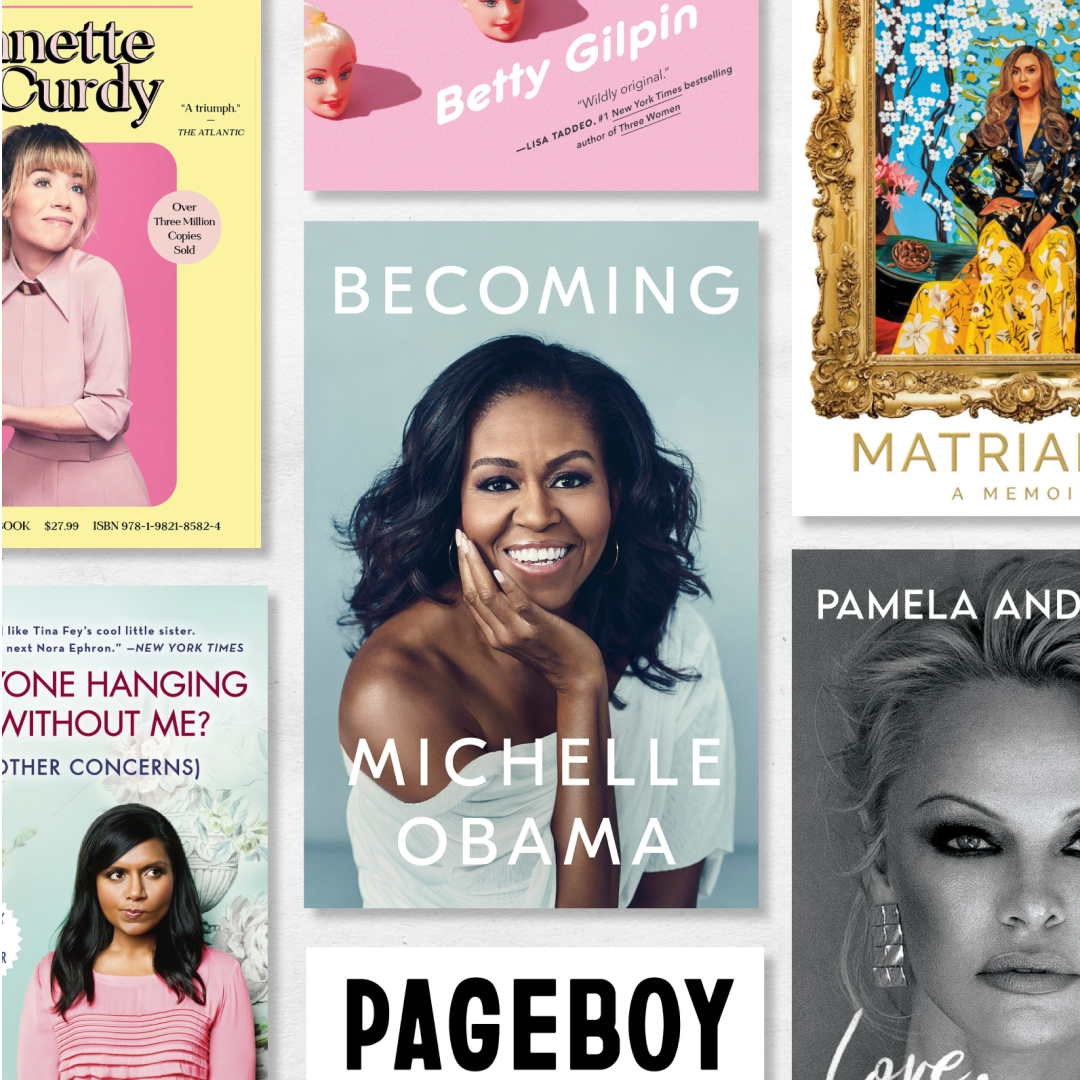

40 Revealing Celebrity Memoirs That'll Change Your Perspective on the Biggest A-Listers

Britney Spears, Demi Moore, Pamela Anderson, and more drop serious bombshells in these pages.

By Andrea Park Last updated

-

13 Books for When You Want to Curl Up and Read About Murder

Calling all fans of "cozy mysteries."

By Liz Doupnik Last updated

-

13 Books That’ll Make You Want to Call Your Mom

These must-reads come from literary mothers like Maya Angelou and Amy Tan, as well as our contemporary faves.

By Liz Doupnik Published

-

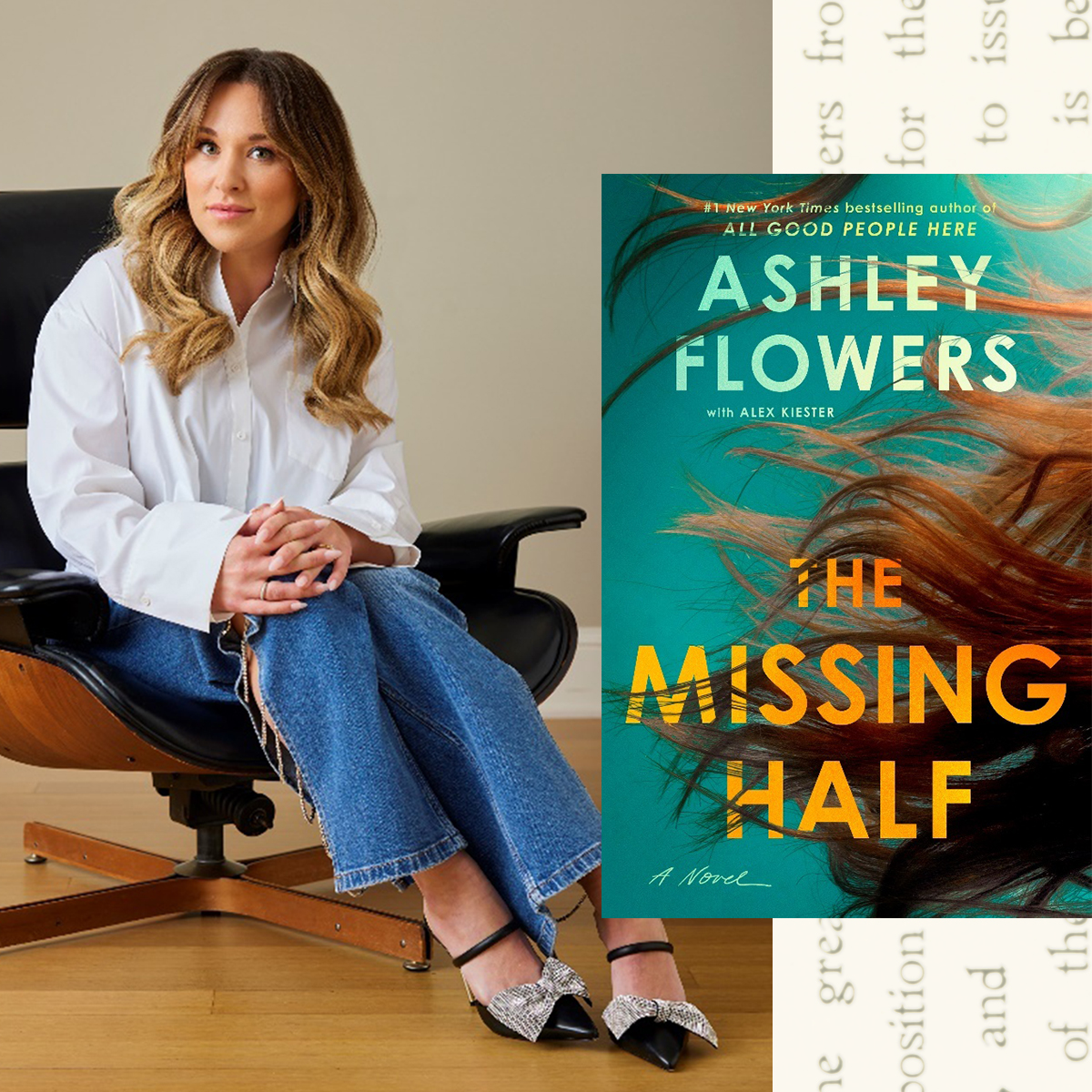

We Asked the Ultimate "Crime Junkie" Ashley Flowers to Share Her Favorite Crime Books

'The Missing Half' author/podcaster knows a good whodunit.

By Sadie Bell Published

-

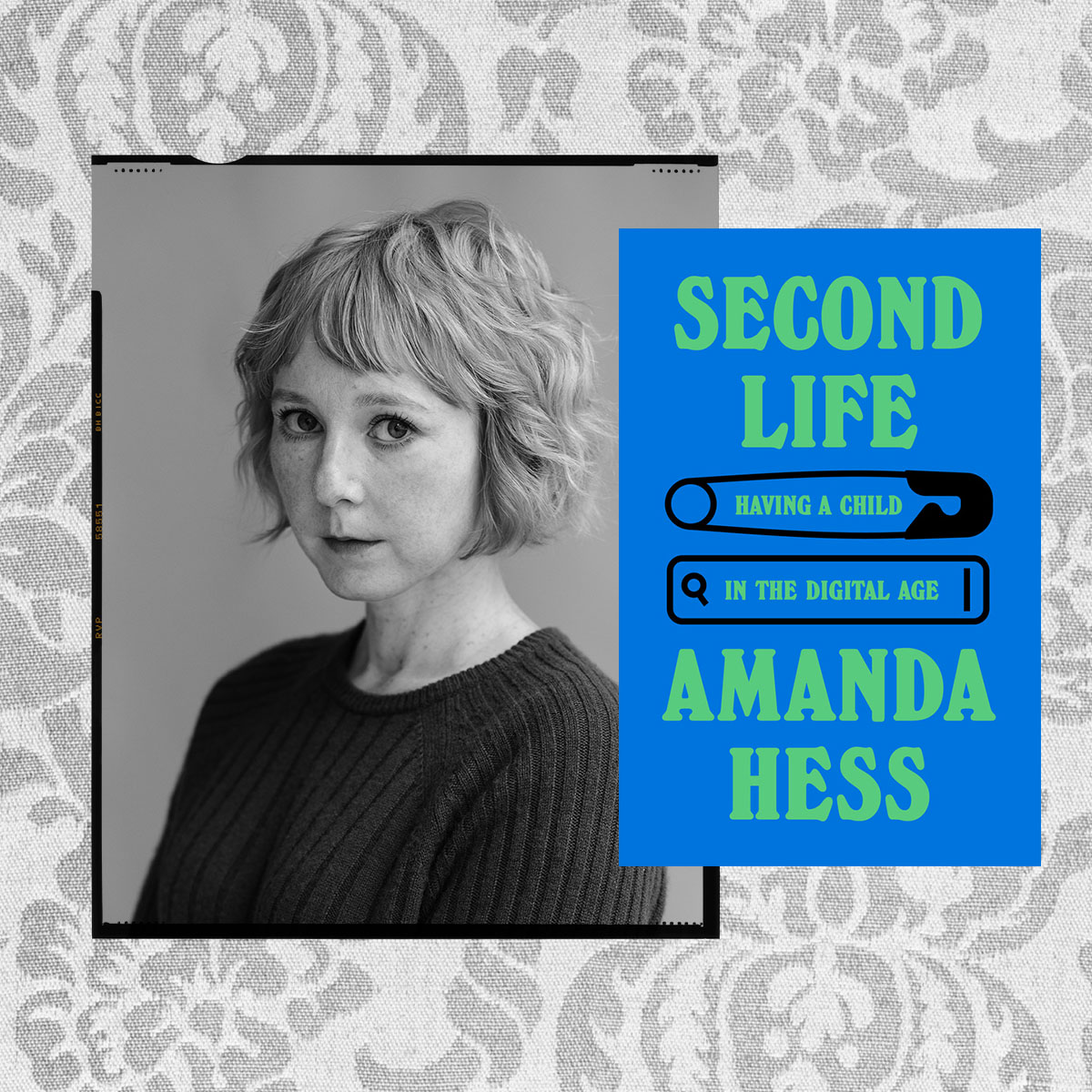

My Pregnancy Obsession Became the Freebirth Subculture

In an excerpt from Amanda Hess's debut memoir, 'Second Life,' she writes about a movement that predates MAHA moms.

By Amanda Hess Published

-

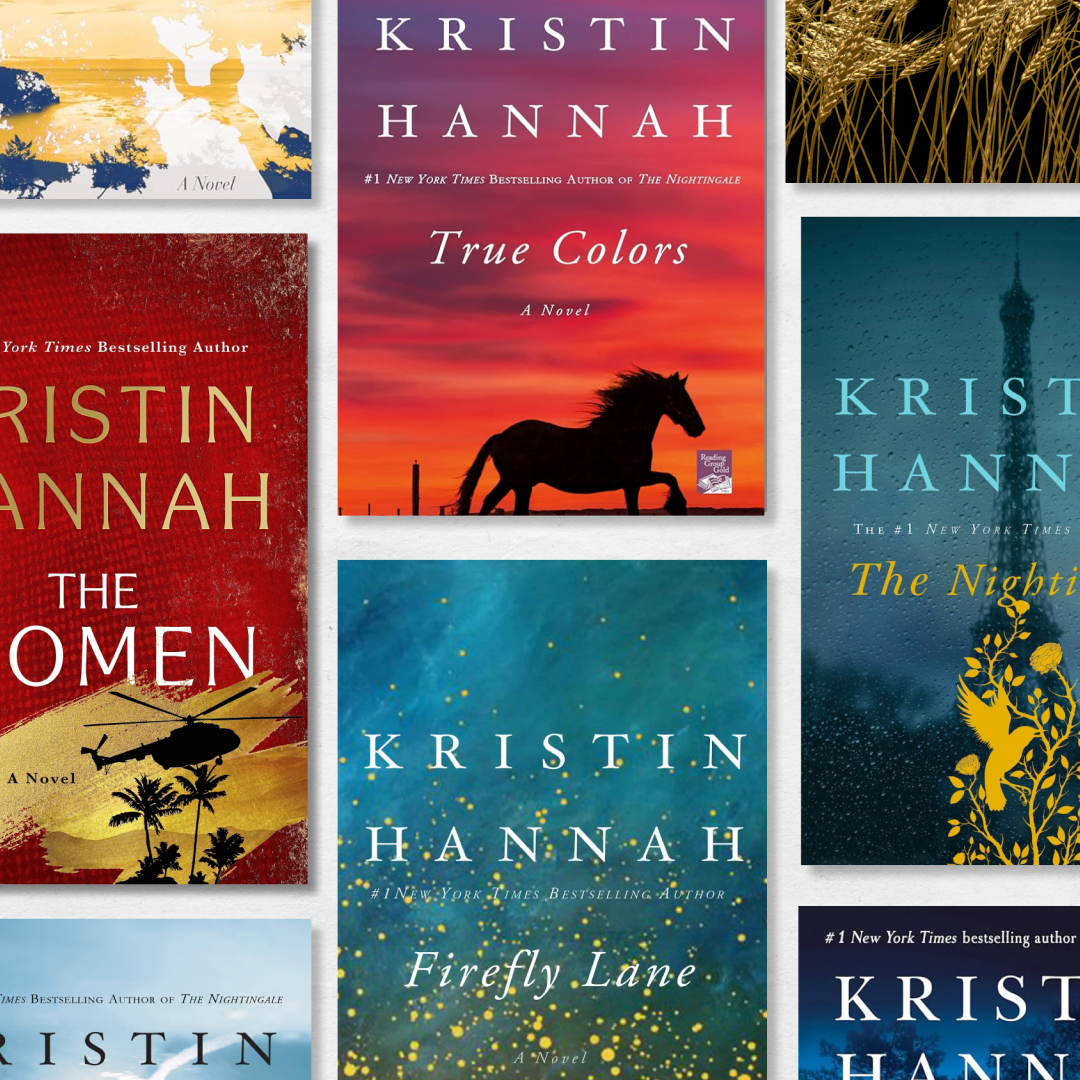

The Best Kristin Hannah Books, Ranked—From 'Firefly Lane' to 'Nightingale'

Get your tissues ready.

By Nicole Briese Last updated

-

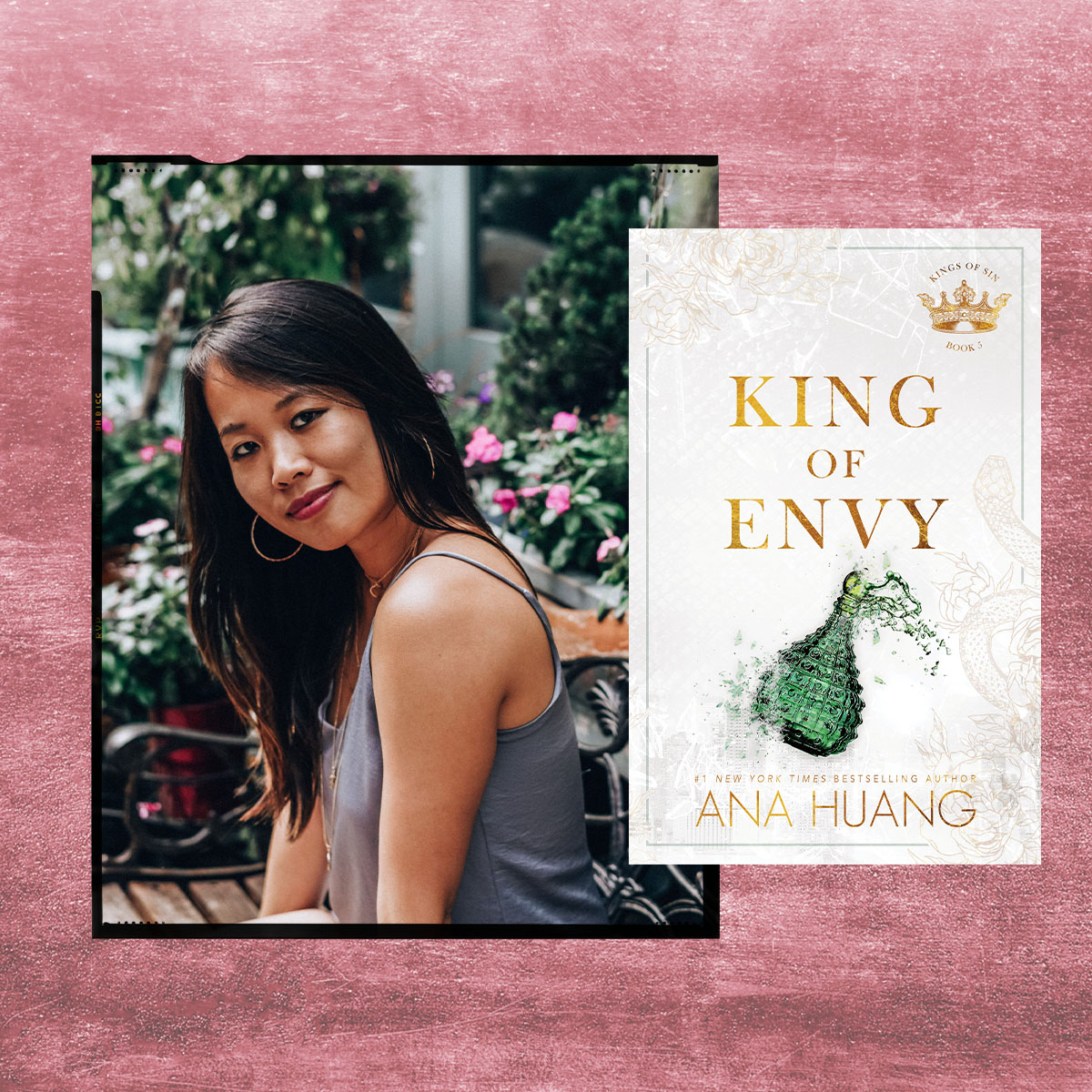

Netflix Is Adapting One of #BookTok's Favorite Romances—Here's What We Know About Ana Huang's 'Twisted Love' TV Series

Could this be the next 'Bridgerton' or 'Tell Me Lies?'

By Quinci LeGardye Last updated

-

Ana Huang Is Ready to Rule Over Romance

With the release of 'King of Envy,' the author, who started as a self-published BookTok favorite, is quickly becoming the queen of the genre.

By Tyler McCall Published

-

Before Lisa Jewell's Most Highly-Anticipated Thriller to Date Hits Shelves, We Ranked Her 10 Best Books

Few do page-turners quite like her.

By Nicole Briese Published

-

Emily Henry Has Reinvigorated Our Love for Romance Novels—We Ranked Every One of Her Books So Far

Her latest novel, 'Great Big Beautiful Life,' just hit shelves.

By Nicole Briese Last updated

-

Climate Fiction So Earth-Shattering You’ll Never Forget to Recycle Again

These dystopian books imagine a future where the worst has already happened.

By Liz Doupnik Published