Farewell, J. Crew

Ours is a bittersweet goodbye.

It is both too soon and too late to say goodbye to J. Crew.

Too late, because the retailer—which, when it filed for bankruptcy on Monday, was carrying a debt burden of $1.7 billion—had been struggling to hold onto its financial and cultural capital for quite some time. When was the last time one could reasonably point to J. Crew as capturing the zeitgeist or setting a trend? Say… eight years ago? (For perspective: Eight years ago, Timothée Chalamet was a sophomore at LaGuardia High School, rapping under the stage name “Timmy Tim.”) Since then, shoppers abandoned the mall for the internet, where J. Crew competed for customers in an increasingly crowded marketplace. Prices climbed as the wares’ quality reportedly deteriorated. Frequent discounting trained customers to wait for a markdown. Sales tumbled.

But it’s also too soon, because before the pandemic forced the inevitable, J. Crew had taken some promising steps to secure its future. Jan Singer, formerly of Spanx, Nike, and Victoria’s Secret, had just taken over as CEO, and cool kid sister brand Madewell was slated to make its initial public offering this spring (that’s been suspended until who knows when).

Besides, it would be presumptuous to believe Chapter 11 is the end of the story. J. Crew announced that it expects to remain “fully operational during this restructuring process” and hopes to reopen its stores as soon as the CDC permits. In fashion, as in life, the things you think are gone forever can always come back around. Did you think that you’d spend spring 2020 texting your ex and ordering face masks from the (formerly bankrupt) American Apparel? Ours is a bizarre, unpredictable time.

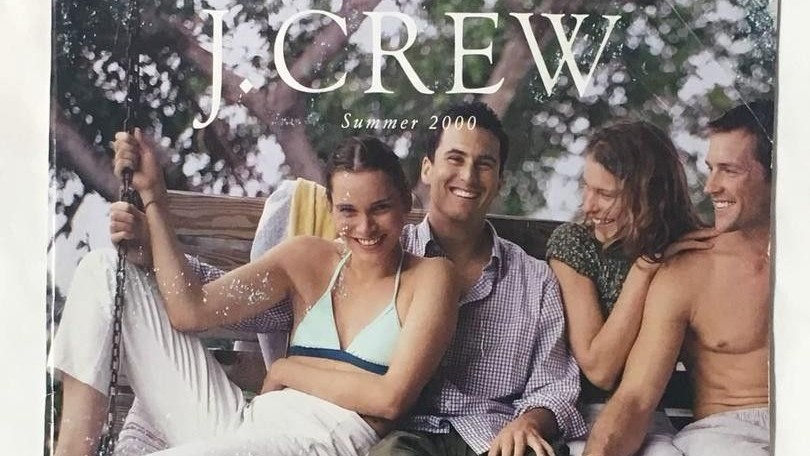

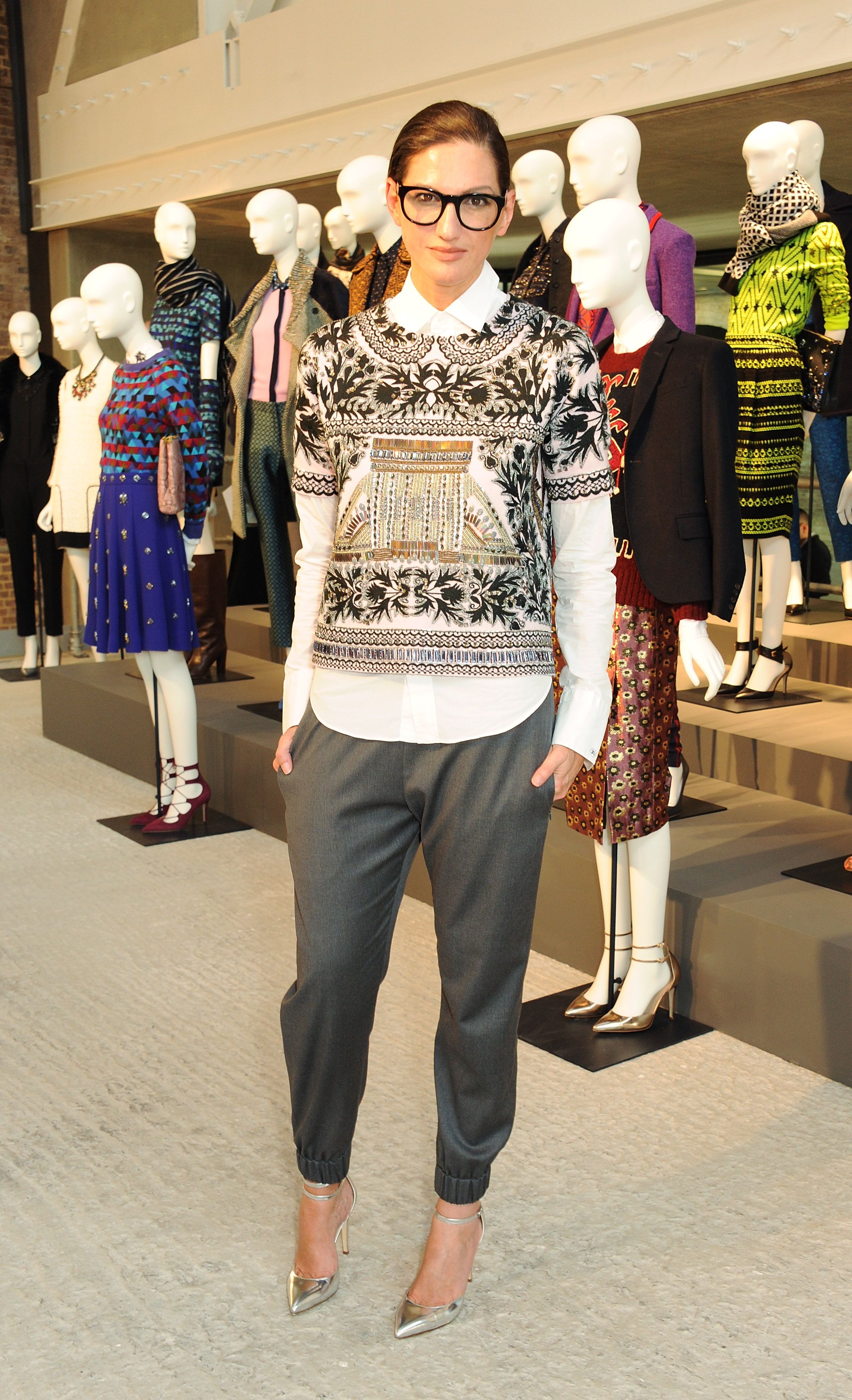

J. Crew started out as an unglamorous staple of practical preppies who ordered its khakis and crewnecks via mail order catalog, the first of which was shot at Harvard’s Weld Boathouse and delivered in 1983. In a timeline that roughly tracks with the Obama years—the mid-2000s to the mid-2010s—J. Crew rose to mainstream mall domination and beyond, serving as a reliable provider of bright daywear, chunky tortoise-shell accessories, and relatively inoffensive bridesmaids dresses. Even when certain items’ economy-oblivious price tags raised eyebrows (in 2008, during the Great Recession, then-executive director Jenna Lyons priced a “J. Crew Collection” sweater at $1,900), the brand charmed the masses.

First Lady Michelle Obama chose J.Crew gloves for Barack's first inauguration, adding to the brand's cachet.

At the height of J. Crew’s cultural dominance, it showed at New York Fashion Week, and Lyons took her sparkly-slouchy aesthetic all the way to the Met Gala. As her profile rose, her signature pieces—thick-rimmed glasses, boyfriend blazers—became a certain type of new generation–preppy girl’s staples. The brand was famously a go-to for First Lady Michelle Obama, who wore green J. Crew gloves to her husband’s first inauguration, slipped on its Barbie-pink pumps to hit the DNC stage, and spent eight years belting the store’s signature cardigans for White House events.

How to explain J. Crew’s appeal? The parts of your wardrobe that had always been drab, J. Crew warmly suggested, did not have to be so. Who says bridal gowns have to be so stuffy? Why can’t you brighten up your grayscale cubicle with a pop of tangerine, or a metallic skirt that gleams like a disco ball under the office fluorescents? Why can’t your boyfriend, who is terrified of color and doesn’t really “get” fashion, wear this shirt? Wild it wasn’t, but for the woman whose idea of sartorial risk was a gray sweater with sequins on it (!), J. Crew was the place to go.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

Even more alluring, J. Crew invited a cheerful dissolution of boundaries between environments and identities. It blurred the line between the playful, anarchic joy of childhood dress-up and the respectable, responsible attire of adulthood; the “serious” person you had to be at work and the fun version you could unleash at happy hour; the glamour of going out and the coziness of laying low.

Jenna Lyons at a J.Crew concept store in London; the one-time executive director became a fashion icon in her own right...for a while.

But after seeing sales climb for years, 2014 brought losses to the tune of $607.8 million. A trio of high-profile departures followed not long after: Lyons, Mickey Drexler (who came on as CEO in 2003 and was swiftly heralded as the mastermind who “resuscitated” J. Crew), and head of menswear design Frank Muytjens all left in 2017. While J. Crew had once shone as the realization of a coherent, instantly-recognizable vision—classic, but with a wink!—it seemed to be having an identity crisis at the exact moment when direct-to-consumer social-first shopping made it even easier than ever for consumers to gratify their fickle tastes elsewhere.

For those with money to burn (for whom a J. Crew purchase represented the “low” half of a high-low look), designer names beckoned. For those who were hungry for the freshest, newest trend, the ever-changing racks at fast fashion outlets provided a perfect fix. As for that mid-range shopper? Lately, she’s likely to be lured by an Instagram ad for some minimalist startup with a sans serif logo that promises sustainability and transparency, and/or the singular purchase—the perfect t-shirt, the best slip dress—that would render all future acquisitions redundant.

Perhaps most damning for the former fashion juggernaut: The original, enduring image J. Crew projected just started to feel…off. The fantasy it’s selling—one that relies on a shared reminiscence of an impossible, Kennedy-esque time and place—doesn’t hit right in an America where the notion of yearning for a “simpler” time has been co-opted by a president whose nostalgia is laced with venom, and whose call to return to the past feels like a threat.

J. Crew is just one mall titan to see its status slip as the 2010s become the 2020s. Victoria’s Secret sales have been plummeting for years, its monopoly on “sexy” dethroned by the inclusive and varied offerings of Fenty and a fleet of lingerie start-ups marketed as progressive. Abercrombie & Fitch, once the unofficial uniform of the hottest kids in high school, is so aware of its diminished clout that it erased its once-ubiquitous logo from its clothes.

While J. Crew is the first major retail casualty of the pandemic, it will soon have plenty of company. In the days since the brand announced its bankruptcy, so did Neiman Marcus. Reuters reported that bankruptcy was on the horizon for Lord & Taylor, a “process from which it does not expect to emerge.” J.C. Penney, Sears, and Brooks Brothers “are among those considering bankruptcies or sales, or looking to trim back their sprawling networks of stores,” according to NPR. So at least you can give J. Crew this: They’re trendsetters once more.

Still, it's possible J. Crew will stage a revival. It wouldn't be the first time. Probably no one expected a mail-order catalog from 1947 called Popular Merchandise to re-emerge in the '80s as the J. Crew it became. Who knows what the brand's next act could be?

Related Story

Jessica M. Goldstein is a freelance writer covering all things culture. Her debut novel, RETRO, is coming out from Ballantine Books in 2026. You can read her in The New York Times, Vulture, McSweeney's Internet Tendency, and more.