"I Would Rather Die Than Stay With These People"

The kidnapping of nearly 300 schoolgirls in northeastern Nigeria this spring brought to light the plight of the people living in the shadows of the fearsome Boko Haram terrorist group. Marie Claire traveled to Chibok to see how the mothers of the missing—and the girls lucky enough to escape—are coping in the midst of crisis.

At the end of a dusty road, surrounded by fields of corn, beans, and wheat, is Chibok, a remote farming community in the northeastern Nigerian state of Borno. Getting to the town—where nearly 300 girls were seized from their boarding school by members of the terrorist organization Boko Haram on April 14—is a long and dangerous journey, punctuated by military checkpoints and miniscule villages with a smattering of homes whose residents live in constant fear of attacks from their Islamist extremist neighbors. In early June, photographer Véronique de Viguerie and I went there to hear from the mothers who desperately want to bring their daughters home, as well as several dozen girls who managed to escape their kidnappers the night of the attack.

Anetou's daughter, Saratou, called her mother while she was being abducted and asked her to pray for her.

Kolo says she frequently rubs her face on daughter Naomi's school uniform to breathe in her smell.

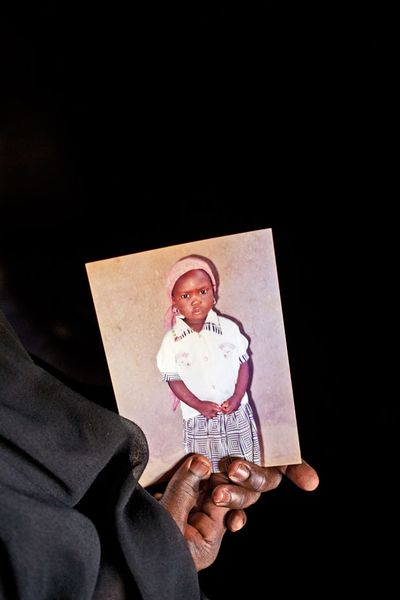

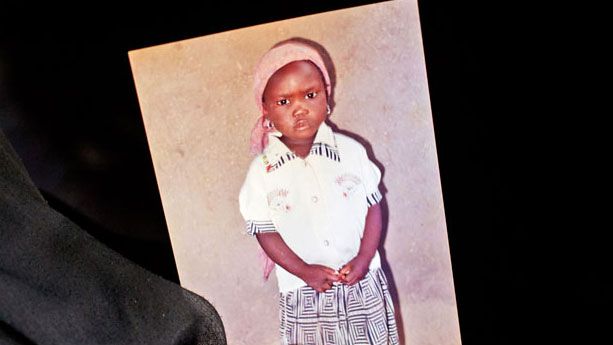

An unnamed mother holds a photo of her daughter, Margaret.

Yana says she sent her daughter, Rifkatu (pictured in childhood), to school so she could have a better life.

Naomi holds a photo of her daughter, Moda.

Airplanes were no longer landing in Borno's capital city, Maiduguri, so our only option was to travel by car from Nigeria's capital, Abuja, at a reckless pace for 15 hours to reach the army-controlled Maiduguri before the 5 p.m. curfew. (The curfew has been in place since President Goodluck Jonathan declared a state of emergency in Borno and the neighboring Adamawa and Yobe states in May 2013, in response to increased attacks by Boko Haram.) For the next leg of our journey, we joined a convoy of five vehicles that also carried Asabé Kwambura, the principal of the boarding school, who was traveling to Chibok the day before a group of government officials from Abuja was scheduled to visit the town for the first time—a month and a half after the attack. (Kwambura had been staying in Maiduguri because her residence at the school was destroyed in the attack.) Two army trucks escorted our group, firing warning shots periodically into the air, but abandoned us when the paved road ended, leaving us alone for the last part of the trip. The dirt road that leads to Chibok is in very poor condition; one of our vehicles got stuck, and another had one of its tires punctured, forcing us to stop for an hour in darkness before we were able to move ahead. When we neared Chibok, a handful of farmers who have formed a vigilante squad to guard the town escorted us the rest of the way. With no military training, they carried bows and arrows, sticks and old rifles, and wore amulets they believe make them impervious to Boko Haram's bullets.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

A "Bring Back Our Girls" protest in Abuja.

Life in this town of about 66,300 exists in sharp contrast to that in the cosmopolitan cities to the south: Abuja and the country's seaside jewel, Lagos, both enjoy the fruits of the oil wealth that has made Nigeria Africa's largest economy. Many residents moved to Chibok from villages nearby, seeking a safe haven—until this spring, they never felt they were in danger. Now Chibokians wonder if there are any safe places left in their corner of Nigeria, feeling forgotten by the government, which has failed to provide them adequate security in the wake of the attack. (Army troops won't venture much beyond Maiduguri, 80 miles south.) The town is at a standstill: Many villagers don't feel comfortable enough to return to work in the fields. Others are considering moving to Maiduguri, but the poorest have no choice but to stay and pray.

Upon arriving in Chibok, we were taken to the home of the principal's brother to stay the night. We rose early in the morning to go to the center of town, where some of the mothers of the missing and the girls who escaped were waiting for the government officials. There are no paved roads or electricity in the town and scarce medical facilities. There was, however, one high school.

Just before midnight on April 14, armed members of Boko Haram, dressed in Nigerian military uniforms, entered the girls' dormitory at the Chibok Government Secondary School. They asked the girls to show them where the food and medicine were stored. They took it all, then set several of the 20 buildings on campus ablaze. "They pretended they were part of the army," says Kumé, 17, one of the students who escaped. "But when they started to burn the school, we realized they were not." The terrified girls were herded into trucks at gunpoint and driven away. All told, Kwambura says her records show 276 girls were taken.

A half hour into the truck ride, Kumé decided to take a chance and jump out of the truck. "I didn't have anything to lose," she says. "I would rather die than stay with these people. I ran through the bush for hours, fearing the whole time that they would catch me." She arrived home at 6 a.m.

News of the attack began to trickle throughout Chibok and the surrounding villages. One mother named Ruth (none of the women in this story wanted their last names used) began walking to Chibok from her village as soon as she heard the news, desperate to know if her daughter, Ladi, 17, was OK. "I reached Chibok early in the morning and went straight to the school," she says. "I stayed there until 2 p.m. in the heat, without eating or drinking anything, waiting for some news of my daughter. But the only thing I found out is that she was among the missing girls." Another girl, Saratou, 17, managed to use her cell phone to call her mother, Anetou, while she was being abducted. "She told us that the girls were in a vehicle moving toward the forest," says Anetou. "She was terrified and asked us to pray for her." Anetou hasn't heard from Saratou since. In school, "the girls were happy," she continues. "They were about to complete their studies and start a new life. And all of a sudden, they lost everything. The government makes promises, but our girls are still in that forest."

Girls on a street in Maiduguri.

The "forest" is the Sambisa game reserve that spans some 23,000 square miles across parts of several states, including Borno. It has been home to elephants, lions, and snakes for decades. Today, it's home to a different kind of danger. In 2002, Mohammed Yusuf, a radical Muslim cleric, formed Boko Haram with the ultimate goal of overthrowing the government and reforming Nigeria as an Islamist state, governed under Sharia law. He was killed during a July 2009 uprising that, while unsuccessful, showcased Boko Haram's might. Its new leader, Yusuf's former deputy, Abubakar Shekau, resolved to avenge his death by waging a bloody campaign, killing both Muslim and Christian clerics and worshippers, politicians, journalists, lawyers, police officers, and soldiers. Every so often, members of Boko Haram swoop in and strike—churches, police stations, prisons, newspaper offices, and even the United Nations headquarters in Abuja in 2011—and then retreat to their encampments in Sambisa, where the overgrown thornbushes and largely untraversable terrain have helped them create a stronghold, much like Afghanistan's mountains provided a haven for the Taliban.

Two years ago, schools, the most obvious target of their hate—Boko Haram loosely translates from the African language Hausa to "Western education is sin"—became the focus of the group's vitriol. "We are attacking the public schools at night because we don't want to kill innocent pupils," the group's then-spokesman, Abul Qaqa, told Abuja's Daily Trust newspaper in March 2012. Around that time, 10 primary schools across Maiduguri were so badly burned, they could no longer be used, according to Amnesty International. Dozens of other schools in the region closed out of fear, some for good—a tragedy in a place where, according to UNICEF, about 40 percent of children do not attend school, giving Nigeria the distinction of being the country with the highest rate of unschooled children in the world.

In 2013, according to an Amnesty International report called "Keep Away From Schools or We'll Kill You" (reflecting the position of Boko Haram), issued in October of that year, the attacks appear to have become even more brutal, as teachers and students were targeted and killed. (In some cases, teachers were killed in full view of students.) The precise number of deaths and schools that have been attacked is unknown. But periodic reports from human-rights groups show a constant drumbeat of assault. In Borno alone, as many as 50 schools were attacked last year. In June, human-rights defenders told Amnesty International that nine children had been killed at a school in Gamboru, a town in Borno near the border of Cameroon; in July, UNICEF reported 48 students and seven teachers had been killed in a series of four attacks in the region; subsequent reports show up to 80 schoolchildren were killed between July and September in the neighboring state of Yobe. Others have been kidnapped instead of being murdered outright.

"We've been documenting these kidnapping cases for over a year in the country's northeast," says Mausi Segun, a researcher for Human Rights Watch in Abuja. "Even though the parents rarely lodge a formal complaint for fear of dishonor, we know that the very few girls who manage to escape or are freed by the army come back pregnant or with a child in tow." In the case of the Chibok girls, Boko Haram released a 57-minute video on May 4, in which leader Abubakar Shekau claimed responsibility for the kidnapping, vowing to "give their hands in marriage because they are our slaves."

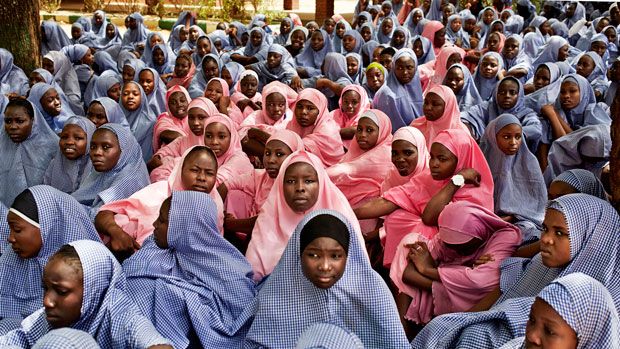

Schoolgirls in Maiduguri.

Some of the girls who escaped, including Kumé (left), were able to take their final exams at this Maiduguri school.

It's against this backdrop that the 1,610 students at the Chibok Government Secondary School chose to go to school. Some of them walked for a day to get there from their villages. They were the first in their families to learn to read and write—and were to become the first to graduate, too. One mother named Saraya says her daughter, Lydia, 17, wanted to go to college and become a lawyer. "Since my daughter has been kidnapped, I can't think of anything but her. I can't focus on anything," she says. Another mother, Yana, whose daughter, Rifkatu, 17, was taken, says she pushed her to get an education. "My dream was to send my daughter to university," she says. "She wanted to get married, but I told her no, you have to carry on with your studies. I wanted her to overtake me and have a better life." Another mother, Kolo, frequently rubs her face on her daughter Naomi's school uniform, breathing in her smell. Crushed by grief, the mothers feel a toxic combination of helplessness and guilt—were they wrong to want more for their daughters? About 10 of the mothers had to be hospitalized. "All my life, I worked hard in the fields so that she wouldn't have to," says Anetou, mother of Saratou. "I wanted to give her a future, but now she's gone."

Government officials from Abuja arrive in Chibok.

The mothers have heard of the international outcry via the hashtag #BringBackOurGirls, which has been shared more than 4 million times, most notably by First Lady Michelle Obama. They are grateful for the support, but wonder: If so many people are looking for their daughters, why haven't the girls been recovered? "The world has to help us get them back," Anetou says. "Deep inside, I know my daughter is still alive." Three weeks after the kidnapping, President Jonathan vowed, "Wherever these girls are, we'll get them out," in a televised address. But it's unclear what, if anything, the government is doing. The U.S. has dispatched unarmed drones to aid in the search, as well as 80 troops to Chad, and the U.K., France, China, and Israel have all offered assistance, but no breakthroughs have been reported. In the meantime, reports say Boko Haram may have taken as many as 80 more women and girls and possibly more than 30 boys, some from three villages near Chibok and others from Kummabza, a village about 100 miles from Maiduguri.

Even if the girls are returned (at press time, they were still being held hostage), how many parents will risk sending their daughters to school again? Principal Kwambura doubtfully runs her fingers over her scar-filled cheeks. Since the high school was attacked, Chibok's seven other schools have been shut down. Kwambura calculates that at least 15,000 students in Borno have had their educations cut short. For the girls who managed to escape Boko Haram the night of the attack—and later took their graduation exams at a heavily guarded school in Maiduguri—an uncertain future awaits. "I keep thinking about that night," says Joy, 17, one of the girls who escaped. "How they came in and took my sisters. Now that I'm safe, I want to become someone in life—maybe a soldier, so I can get rid of Boko Haram."

Related:

Anne Hathaway Takes to Megaphone in Nigeria Kidnapping Protest

Angelina Jolie: Nigerian Kidnappings are 'Unthinkable Cruelty'

Senators to Reintroduce International Violence Against Women Act in Wake of Nigerian Kidnappings

What You Need to Know About the Nigerian Schoolgirls Kidnapping

Photo Credits: Veronique De Viguerie/Reportage by Getty Images