Celebrity

All things celebrity, from royal family news and award show coverage to celebrity news updates.

Explore Celebrity

-

Princess Diana Relied on a Much Older "Mother Confessor" For Comfort and Support

"They used to laugh a lot, see each other all the time, more than anyone else I could mention."

By Kristin Contino Published

-

Why Duchess Sophie Left her Scarf at Heartbreaking Memorial in Bosnia and Herzegovina

The Duchess of Edinburgh marked the 30th anniversary of the Srebrenica Genocide.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

The Ultimate Royal Guide to London

A royal editor's tips on where to stay, shop and eat like a queen.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

Exclusive: Royal-Favorite Designer Anna Mason Is the It Girl British Label You're Probably Sleeping On

Beloved by Kate and Pippa Middleton and Zara Tindall, Mason's designs are a new Hamptons fave.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

Royal Girlfriend Harriet Sperling Is Following in the Royal Family's Fashion Footsteps at Wimbledon

She's already got the royally approved brands on tap.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

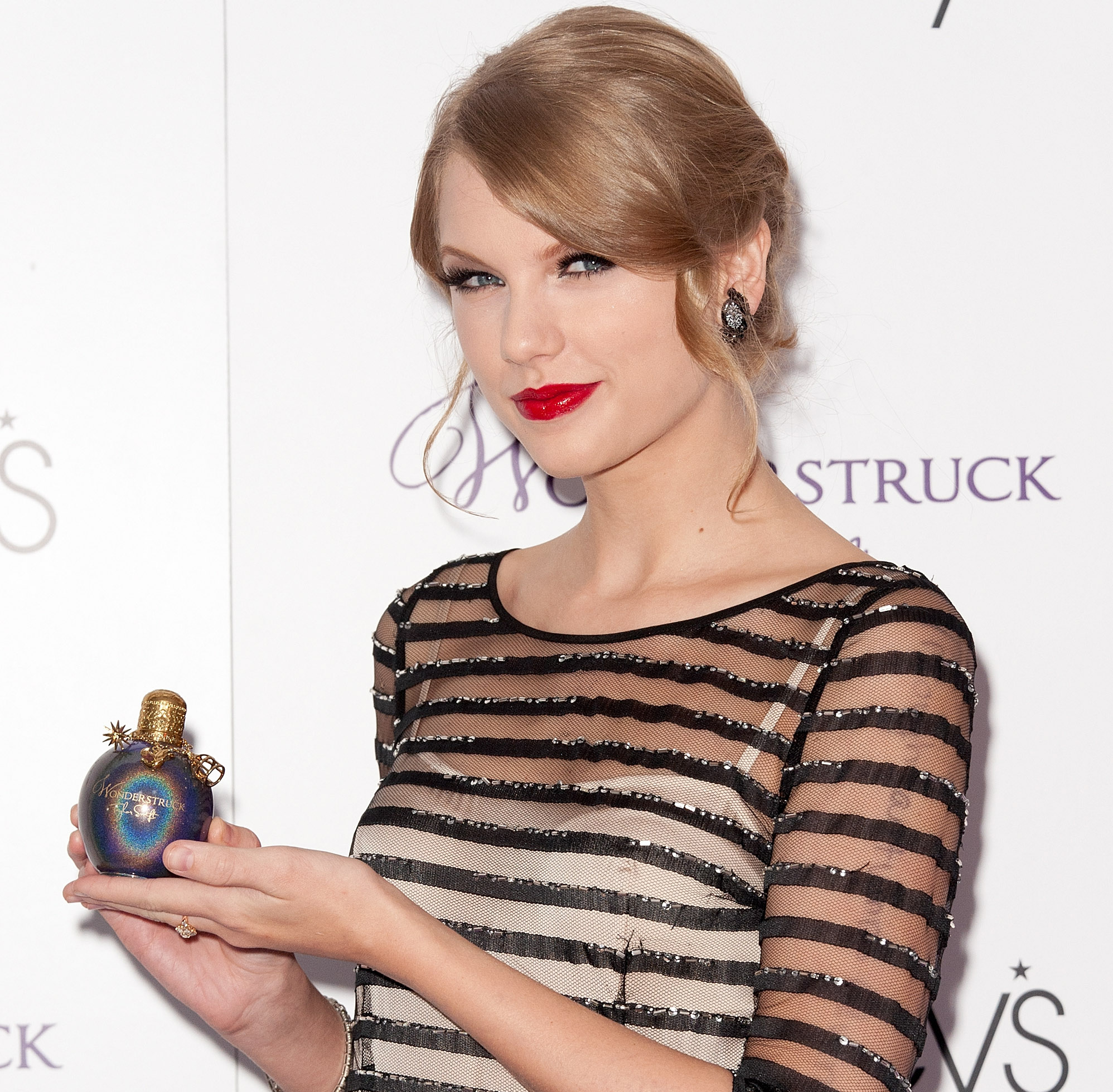

The Most Beloved Celebrity Scents Ever

From the sweet and fruity to the dark and seductive.

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

Princess Charlene Pays Tribute to Grace Kelly in Black and White Gown

The Monegasque royals shared a sweet moment in France.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

Photos of the Royal Family at Polo Matches Over the Years

Candid moments from the "sport of kings."

By Katherine J. Igoe Published

-

Queen Elizabeth Proved She Was in on the Joke During Hilarious Speech Where She Made Fun of Herself

Prince Philip definitely would've approved.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

A Royal Superfan Is Planning to Eat a Slice of Queen Elizabeth’s 1947 Wedding Cake

It's...a choice.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

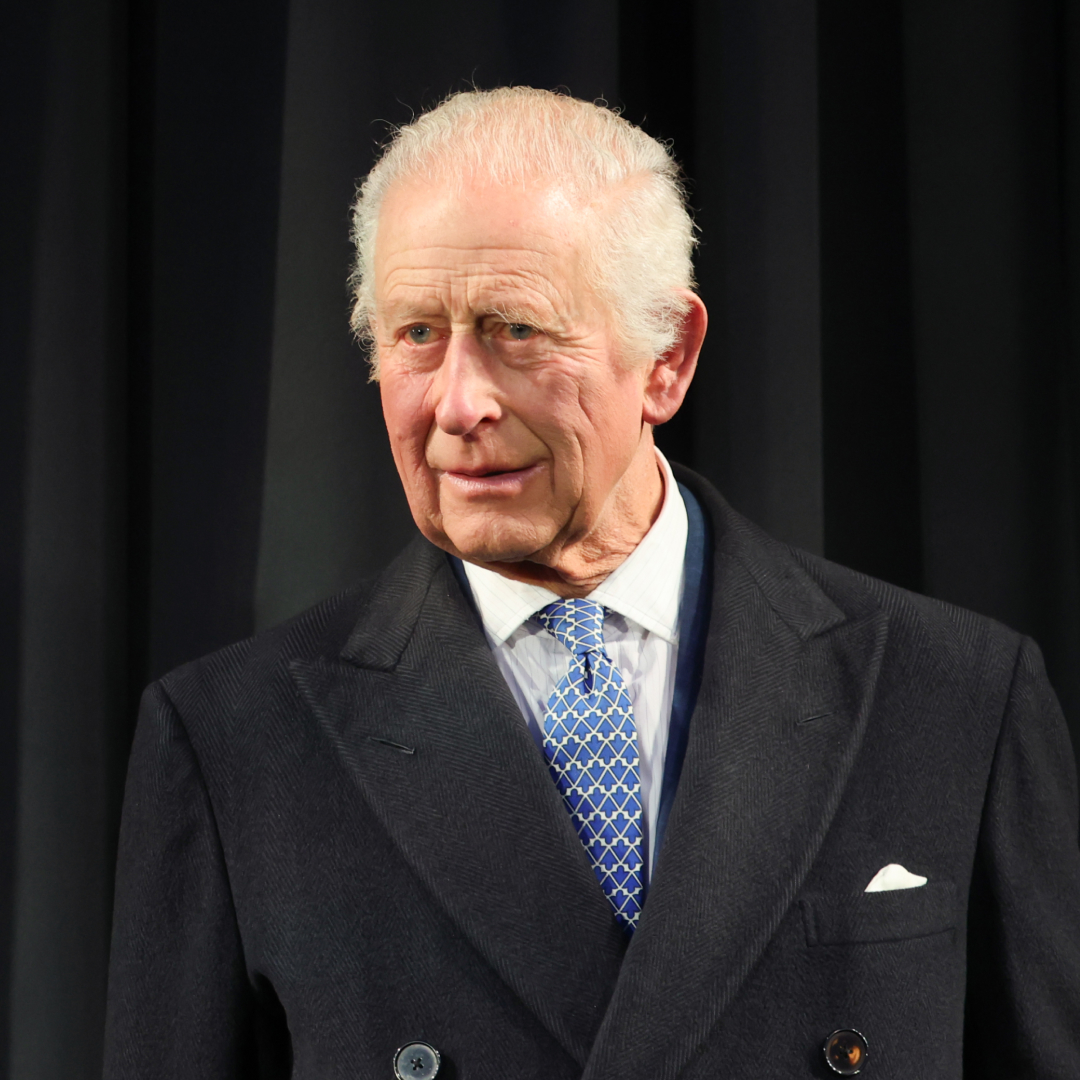

King Charles Gave President Macron a Hilarious Warning About the Royal Dogs During French State Visit

Queen Elizabeth's legacy continues.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

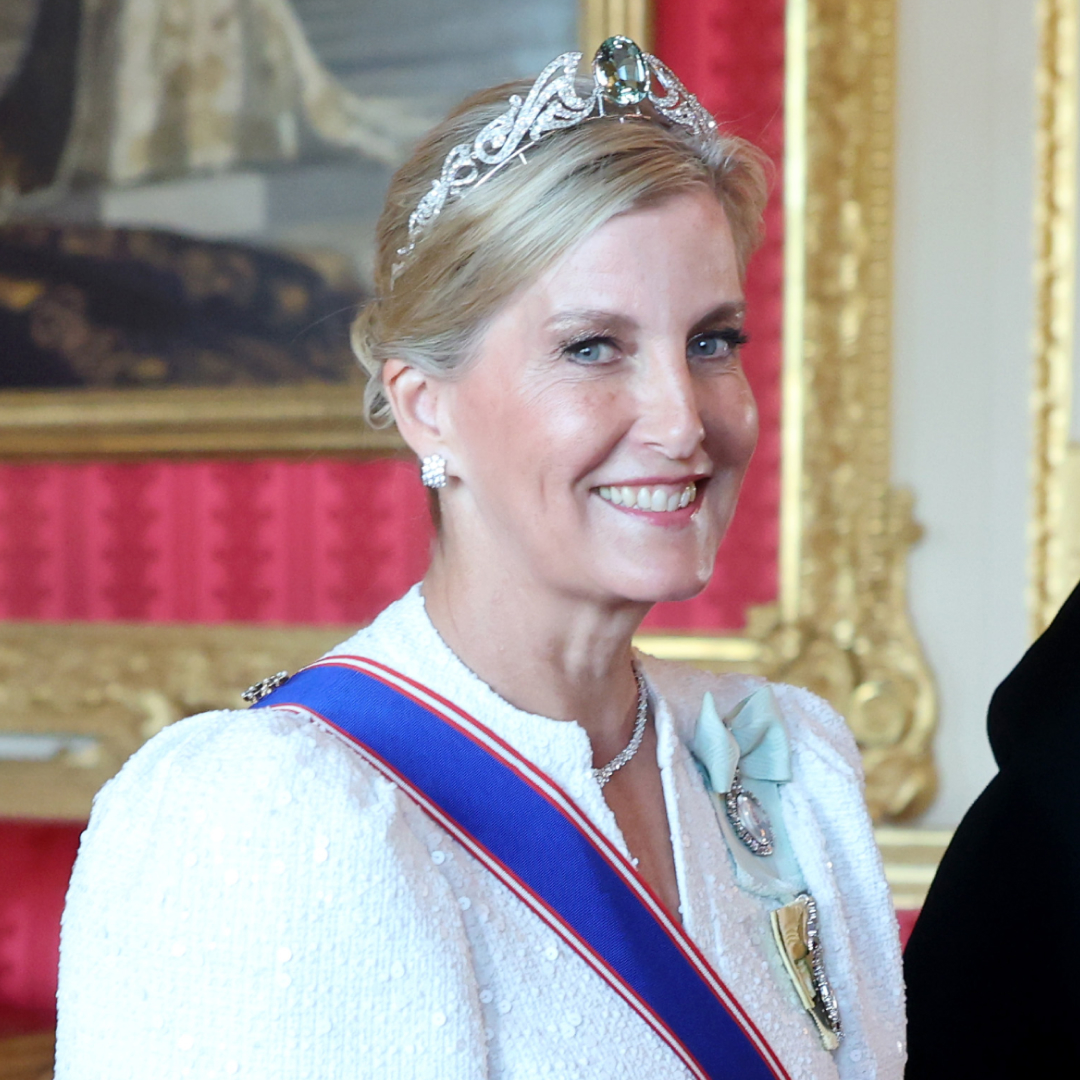

Duchess Sophie’s Sparkling Aquamarine State Banquet Tiara Is Hiding a Clever Trick

Her hair is full of secrets.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

Princess Anne Pairs a 1970s Tiara With a Surprising New Hairstyle at French State Banquet

Even the Princess Royal switches up her coiffure sometimes.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce on Her "Final Year" as a Professional Athlete: "This Isn't a Farewell Tour"

"I love where I'm at in this journey."

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce on Returning to Record-Breaking Running After Becoming a Mom

She had to balance being a mom with track and field.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce Breaks Her Silence on Dropping Out of Her Last-Ever Olympic Race

"I wanted to do it for my country, but then I had to ask 'what’s right for me?'"

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Princess Kate Breaks Her Tiara Drought in Dramatic Red Caped Gown

It's her first state banquet since 2023.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

Princess Diana's Niece Embraces Roman Holiday Style in Gucci and Aquazzura

Princess Diana's niece is soaking up la dolce vita.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

Former Royal Chef Reveals Secrets Behind Lavish State Banquets

From "perfect" pears to fish caught by the royals themselves.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

Princess Kate Delivers a French Fashion Rewind in Vintage-Inspired Dior Blazer

Ooh la la.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

Queen Elizabeth Was Considered "Dull" by Many and Didn't "Have a Lot to Say"—But it Was a Strategic Move at Times

She said it best when she said nothing at all.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

This Surprising Royal Was “The Most Popular” Among Staff

"They all love him."

By Kristin Contino Published

-

Duchess Sophie Goes from Memorial Service Appropriate to Wimbledon Cool With a Simple Blazer Swap

The Duchess of Edinburgh made a quick change.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

Reality Star "Mortified" After "Breaking Royal Protocol"

"King Charles kept looking towards her."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Pippa Middleton Wears Duchess Sophie's Favorite Summer Shoe Trend

Princess Kate's sister enjoyed a rare outing with her husband at the British Grand Prix.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

The Motto Queen Camilla Held on to "Whenever Things Got Bad"

"That's what's kept her going, I think."

By Amy Mackelden Published