Documentary

Discover something new to watch, or catch up on the news and gossip, from the best in the documentaries genre.

-

Cue "Thunderstruck!" The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders Return for 'America's Sweethearts' Season 2 This Month

Here's what to know about the second installment of the sports docuseries, including which dancers are returning.

By Quinci LeGardye Last updated

-

Breaking Down the Harrowing True Story of Fred and Rose West, Including the Tragedy of What Happened to Their Children

Netflix's new true crime docuseries 'A British Horror Story' uncovers the case of two of the U.K.'s most heinous serial killers.

By Radhika Menon Published

-

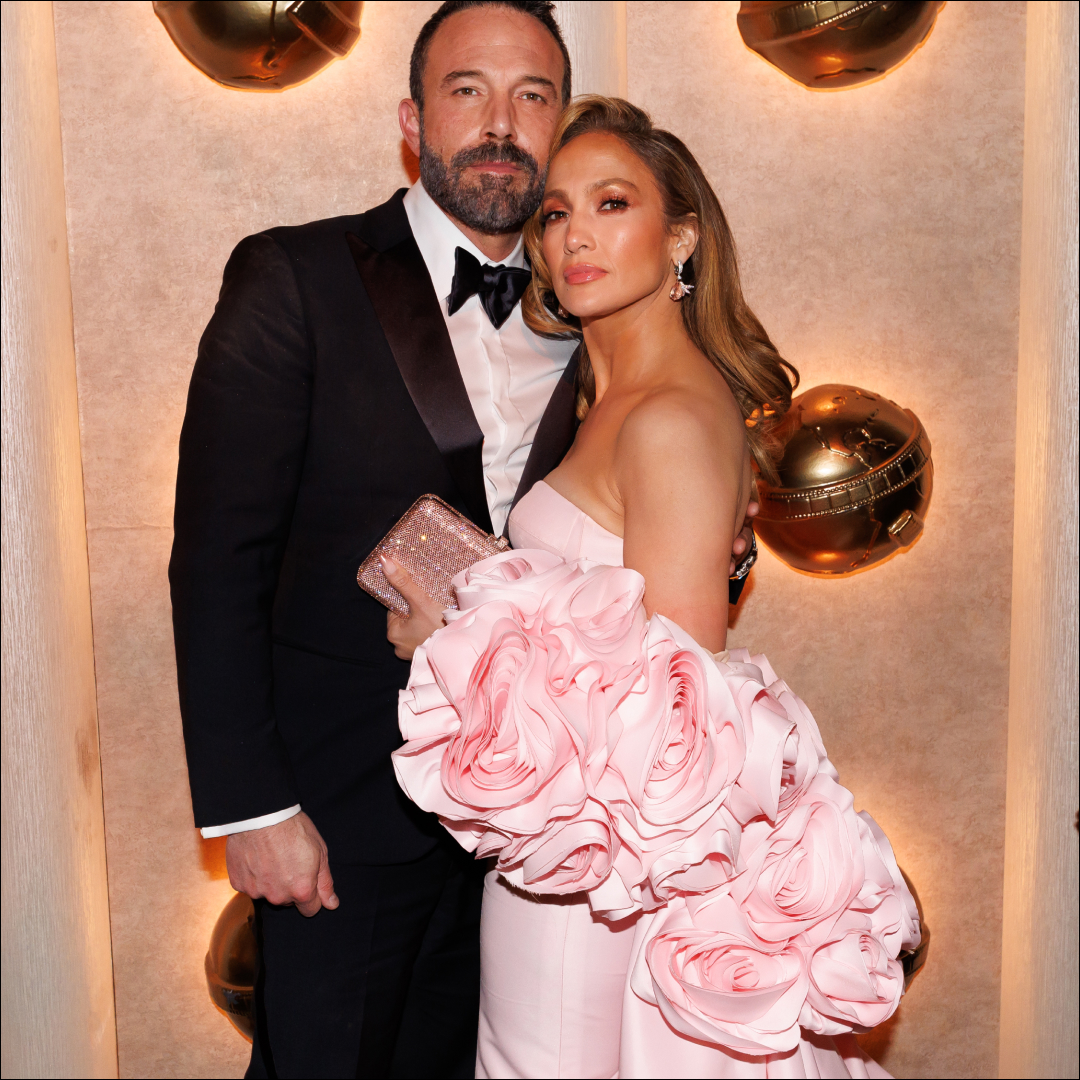

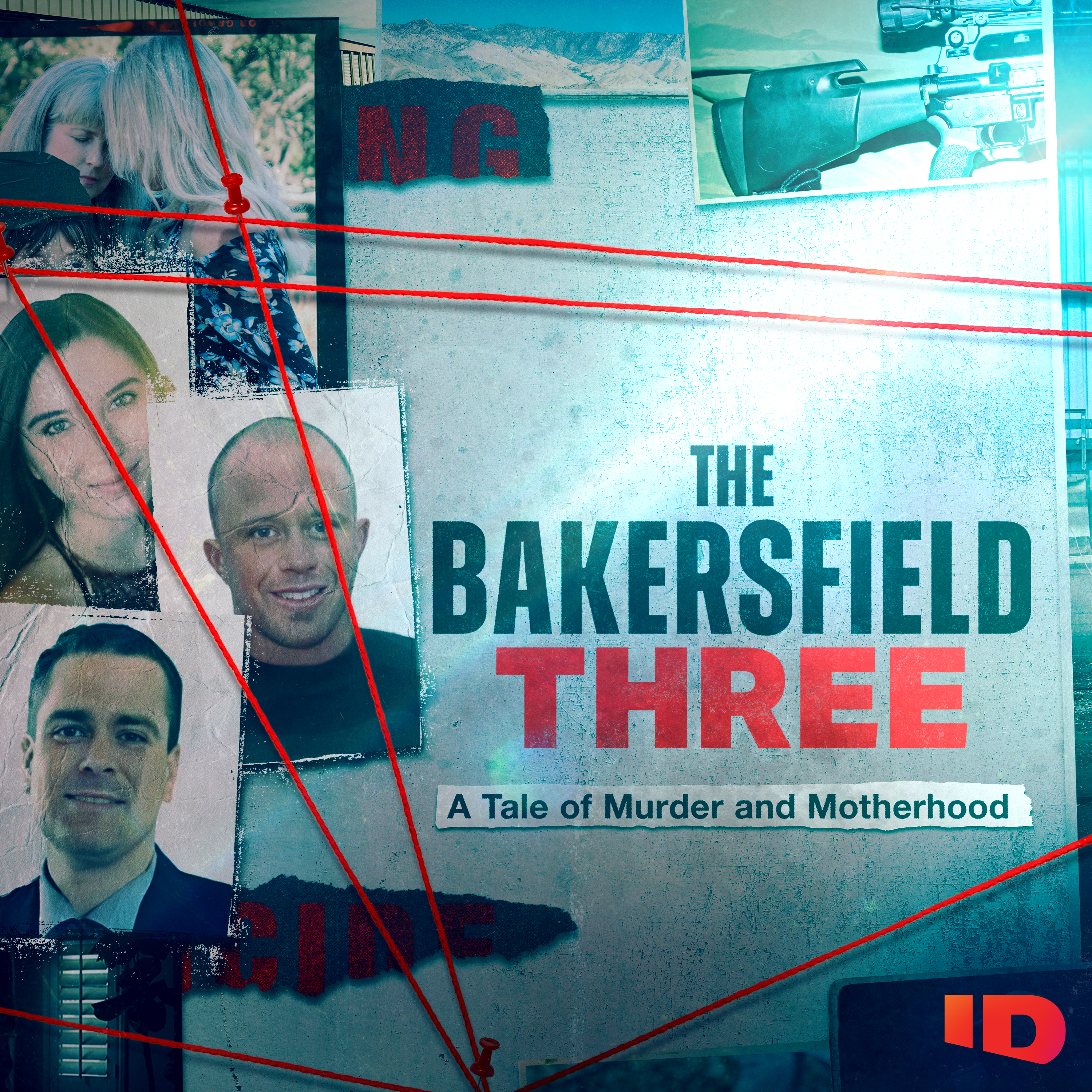

Don't Miss the Premiere of True-Crime Series 'The Bakersfield 3'

Here's what to expect.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

'Bad Influence' Charts the Demise of a Popular Social Media Squad—Here's Where the Kidfluencers Are Now

The names in the Netflix docuseries have fallen out of touch with subject Piper Rockelle.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

Netflix's 'Bad Influence' Is Its Latest Harrowing True-Crime Docuseries. Here Is Where the Subject Piper Is Now

The documentary examines a kidluencing empire and the lawsuit against it.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

The Best True Crime Documentaries of the Year So Far Add Depth to Cases That Took Social Media by Storm

You're going to want to add these to your queue.

By Abby Monteil Last updated

-

16 New Documentaries That Are Sure to Be Your Next Obsession

From the untold stories behind fashion and music icons to revolutionary Oscar-winners.

By Abby Monteil Last updated

-

'Con Mum' Chronicles How Graham Hornigold Was Scammed By His Long-Lost Mother—Here's Where He Is Now

The renowned pastry chef is on the hook for over £300,000.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

Meghan Markle Reveals Impressive Hidden Skill in New Netflix Doc

What can't she do?

By Kristin Contino Published

-

Two of 'The Later Daters' Found Love on the Netflix Dating Show—Are the Couples Still Together Today?

Plus, which cast member got engaged after filming!

By Quinci LeGardye Last updated

-

2024's Best True-Crime Series and Documentaries Are Full of Cults, Scams, and Horrible Exes

Features Are you ready to play armchair detective?

By Quinci LeGardye Last updated

Features -

Queen Camilla Was "Openly Crying" When Learning of Case That Inspired Her Groundbreaking Work in New Documentary

The Queen's inspiring work "doesn't always get a lot of coverage," one expert says.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

In 'Zurawski v. Texas,' the Post-Dobbs Reality Is Darker Than You Could Have Imagined

A new documentary, produced by Hillary and Chelsea Clinton, and Jennifer Lawrence, shows just how catastrophic anti-abortion bills are—and what’s at stake if we stop fighting them.

By Jessica Goodman Published

-

Prince William Asked If He's Trying to "Escape the Work" During New Documentary

The moment was caught on film while he volunteered at a homeless charity.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

Prince William Reveals Why Princess Diana Would Think He'd Gone “Mad”

He’s got some big ideas.

By Kristin Contino Published

-

'Breath of Fire' Is Your Next Cult Docuseries Obsession—Here's What to Know About Its Scammer Yogi Subject, Guru Jagat

HBO's latest true-crime doc explores the fall of a celebrity yoga instructor and her mysterious death.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

Prince William Says He Wants to "Challenge Homelessness" While Promoting New Documentary

"We see it every day in our lives."

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

The Late Queen Elizabeth “Didn’t Like” Former President Donald Trump, New Documentary Claims

“The Queen said that.”

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

Prince Harry Sits Down for Documentary to Speak About His Mission to Continue His Fight Against the U.K.'s Tabloid Press

Harry is expected to discuss the phone hacking scandal he was involved in alongside other celebrities like Hugh Grant in ‘Tabloids on Trial,’ out later this month on ITV.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Prince William Steps In Front of the Camera in New, Revealing Documentary

The two-part docuseries will provide a behind-the-scenes look into one of the Prince of Wales' royal initiatives.

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

Where Are the Stars of 'America's Sweethearts: The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders' Now?

Most importantly, here's who returned to this season's training camp.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

The 30 Best Fashion Documentaries Available to Stream

From inspiring designer profiles to shocking exposés about industry scandals.

By Andrea Park Last updated

-

Melanie Wilking Says She Has "Not Heard" From Her Sister Miranda Since 'Dancing for the Devil' Premiered

The dancer's family claims she's been in an alleged TikTok cult for years.

By Quinci LeGardye Last updated

-

Where Every Subject of Netflix's Hit TikTok Cult Docuseries 'Dancing for the Devil' Is Now

Some dancers in the true crime docuseries are still in the alleged cult—and some have filed a lawsuit.

By Quinci LeGardye Last updated

-

As Royal Family Drama Reaches Its Apex, Queen Camilla Is Filming a Documentary

Admittedly a most unexpected move from Her Majesty.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Travis Kelce is Producing a New Documentary on Jean-Michel Basquiat

Is there anything this 3-time Super Bowl champ can't do?!

By Danielle Campoamor Published