marriage

Discover expert analysis and the modern take on marriage, brought to you by Marie Claire.

-

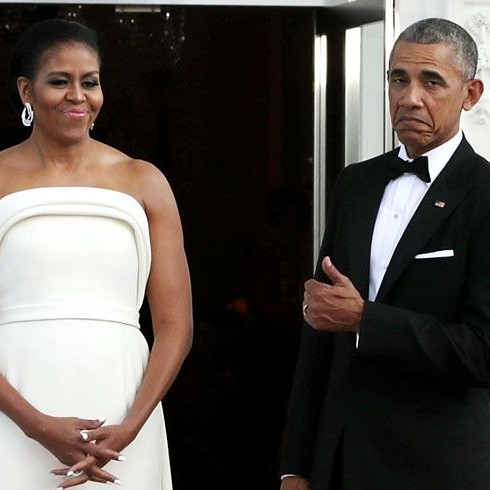

Barack Obama Says He's Been in a "Deep Deficit" With Michelle

The former POTUS revealed how he's attempting to make it up to his wife.

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Cher Considered Suicide While Trapped in "Loveless Marriage" With Sonny Bono

"I saw how easy it would be to step over the edge."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Pamela Anderson Says It's "Tough" Staying Single After Dating So Many "Bad Boys"

"I didn't go after any bad boys. Bad boys came after me!"

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

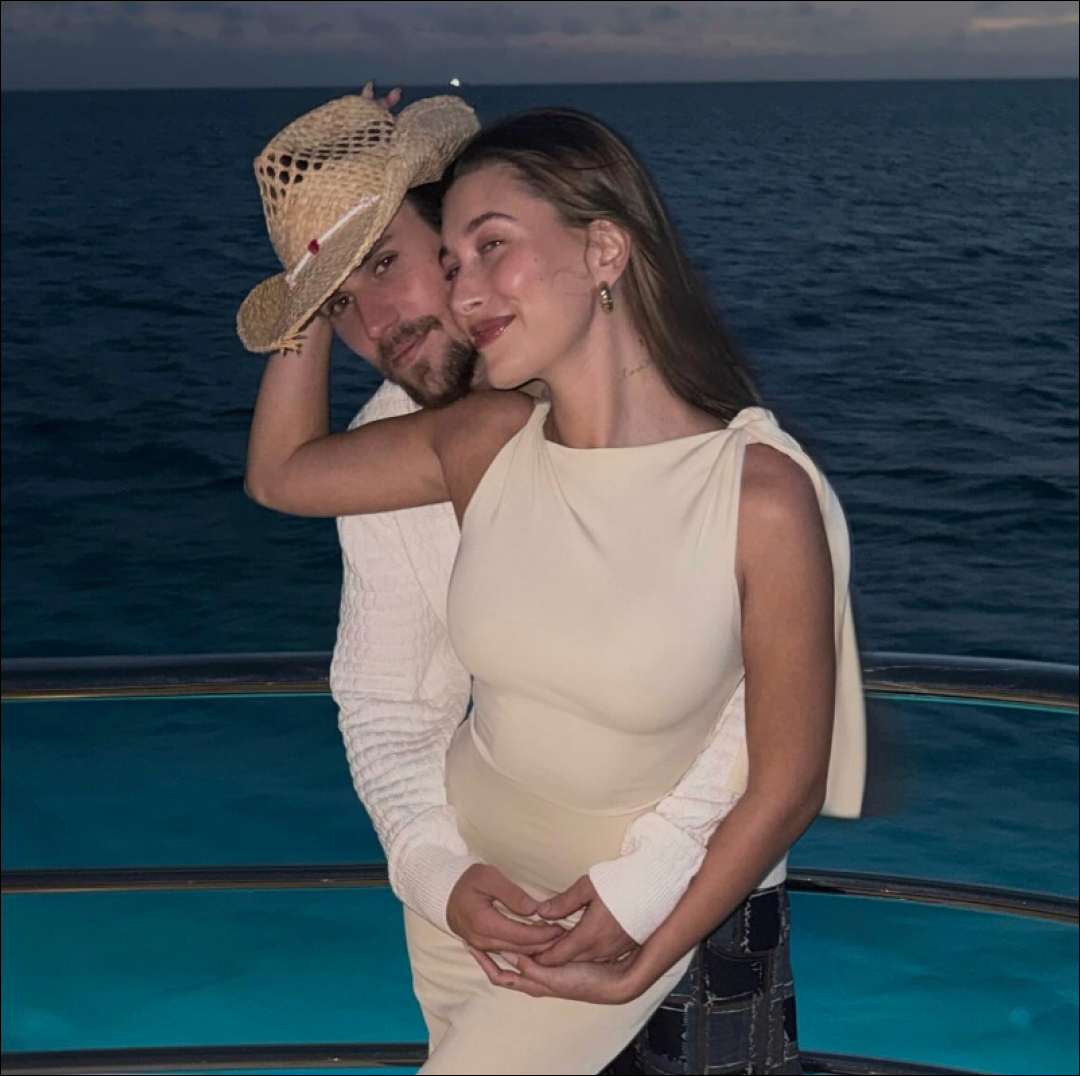

Hailey Bieber Shuts Down Rumors About Her Marriage to Justin Bieber

“Sorry to spoil it.”

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

Kirsten Dunst Opens Up About Her Marriage to Fellow Actor (and Frequent Co-Star) Jesse Plemons

“I trust his opinion more than anyone.”

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Prince Harry Is “Putting Pressure” on Meghan Markle to Accompany Him to an Event in the U.K., and It’s Causing Tension In Their Marriage, Royal Expert Claims

Meghan has reportedly said in the past that she “never wants to set foot again in England.”

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Emma Heming Willis Shuts Down Narrative There's "No More Joy" in Marriage to Bruce Willis Amid Dementia Diagnosis

She set the record straight on Instagram.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Hailey Bieber Says Her Marriage Is "For Life" in Moving Birthday Tribute To Husband Justin Bieber

"Words could never truly describe the beauty of who you are."

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

Natalie Portman, Who Never Comments on Her Marriage, Just Commented on Her Marriage

After rumors swirled that her husband, Benjamin Millepied, had an affair, she called speculation about their relationship “terrible.”

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Joey King Got Married at a Place Called "Same Day Marriage" With a Dollar-Store Bouquet

Um, incredible.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

The Super Bowl Might Not Be the Only Milestone Moment in Usher's Life This Week—Is He About to Get Married?

When in Vegas!

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Justin and Hailey Bieber’s Marriage Apparently Works Because of Three Major Reasons

The Biebers are five years into marriage and are “in a good place” after navigating “growing pains.”

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Doja Cat's Fake Tattoos Are a Genius Marriage of Beauty and Fashion

The look, and the Turkish-British designer behind it.

By Gabrielle Ulubay Published

-

Prince Harry and Meghan Markle Aren't "As Openly Passionate" With Each Other as They Used to Be, Body Language Expert Claims

Fair enough!

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Queen Margrethe of Denmark Might Have Just Abdicated the Throne to Save Her Son’s Marriage

Margrethe’s bombshell announcement will leave the world without a reigning queen in just two weeks’ time—and follows a scandal involving her heir.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Willie Nelson Sweetly Opened Up About His Marriage of 31 Years to Wife Annie D'Angelo

She's there for him.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Nick Jonas and Priyanka Chopra Dressed to the Nines to Celebrate Five Years of Marriage

Who said the honeymoon phase only lasted three months?

By Gabriella Onessimo Published

-

Drybar Founder Alli Webb on the "Messy Truth" About Marriage and Entrepreneurship

Can a successful career and marriage coexist? The serial entrepreneur says this one habit could have saved her relationship.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

The Timing of Chris Appleton and Lukas Gage’s Divorce Filing Is A Little Wild

The couple are splitting after just shy of seven months of marriage.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

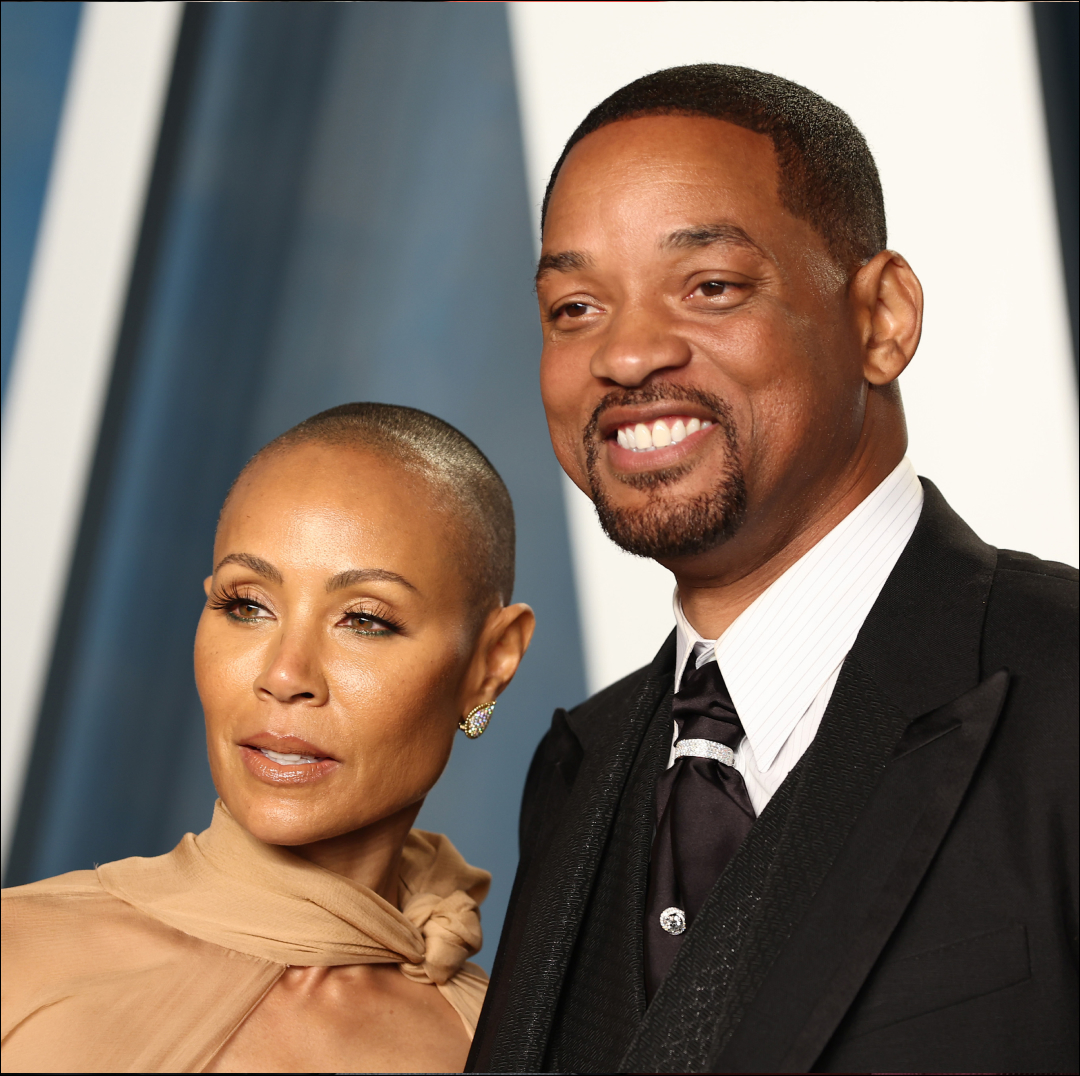

Jada Pinkett Smith's Long Road to Self-Acceptance

“I wake up every morning and I’m glad to be me—finally.”

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s Exit from the Firm Has Reportedly Had “A Huge Impact” on Prince William and Princess Kate and Their Marriage

“At times it can feel like they are cracking under this relentless pressure.”

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Snapchat's Rajni Jacques on Why Tech Is Fashion's Next Frontier

"Fashion does not only live in this realm."

By Emma Childs Published

-

Victoria and David Beckham Get Extraordinarily Candid About the Most Difficult Season of Their 24-Year Marriage

Of the rough patch, Victoria said it was “the most unhappy I’ve ever been in my entire life.”

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Joshua Jackson Was Reportedly Blindsided By Jodie Turner-Smith Filing for Divorce Earlier This Week

“Joshua obviously didn’t realize it was this bad, that Jodie was this unhappy.”

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

Jodie Turner-Smith Files for Divorce from Joshua Jackson After Nearly Four Years of Marriage

The two share a three-year-old daughter and have been together since 2018.

By Rachel Burchfield Published

-

It’s Official: Ariana Grande, Dalton Gomez Simultaneously File for Divorce After Two Years of Marriage

Thankfully, it seems to be as amicable as any divorce can be.

By Rachel Burchfield Published