nutrition

Discover expert analysis and the modern take on nutrition, brought to you by Marie Claire.

-

I Swapped My Pricey Serums for This Inexpensive Hair Growth Solution

The results speak for themselves.

By Marisa Petrarca Last updated

-

It Turns Out I've Been Using Rosemary Oil for Hair Growth All Wrong

A dermatologist set me straight—and on the path to longer, stronger hair.

By Samantha Holender Last updated

-

Shop For Moisturizer the French Way and Spend Less Than $15

This beauty insider secret gave me the glowiest complexion imaginable.

By Emma Aerin Becker Last updated

-

Every Diet That Actually Works Has These 10 Traits in Common

According to health and nutrition experts.

By Marie Claire Last updated

-

Color Me Shocked But This Face Oil Actually Healed My Acne Breakouts

Buying Guide My skin is looking better than ever.

By Samantha Holender Last updated

Buying Guide -

I Finally Achieved Glass Skin and It's Thanks to This K-Beauty Staple

Magic in a jar.

By Marisa Petrarca Last updated

-

Meet the Growth Products that Helped My Hair Reach My Waist

Presenting shampoos, oils, and supplements that actually work.

By Gabrielle Ulubay Last updated

-

Retinol Creams Will Smooth Fine Lines—Without Irritation

Plus, expert tips on how to use the game-changing skincare ingredient.

By Taryn Brooke Last updated

-

19 Hair Growth Vitamins for Your Healthiest Hair Ever

Shine from the inside out.

By Gabrielle Ulubay Last updated

-

Is Colostrum the New Collagen?

Doctors and wellness professionals have a lot to say about TikTok's supplement of the moment.

By Gabrielle Ulubay Published

-

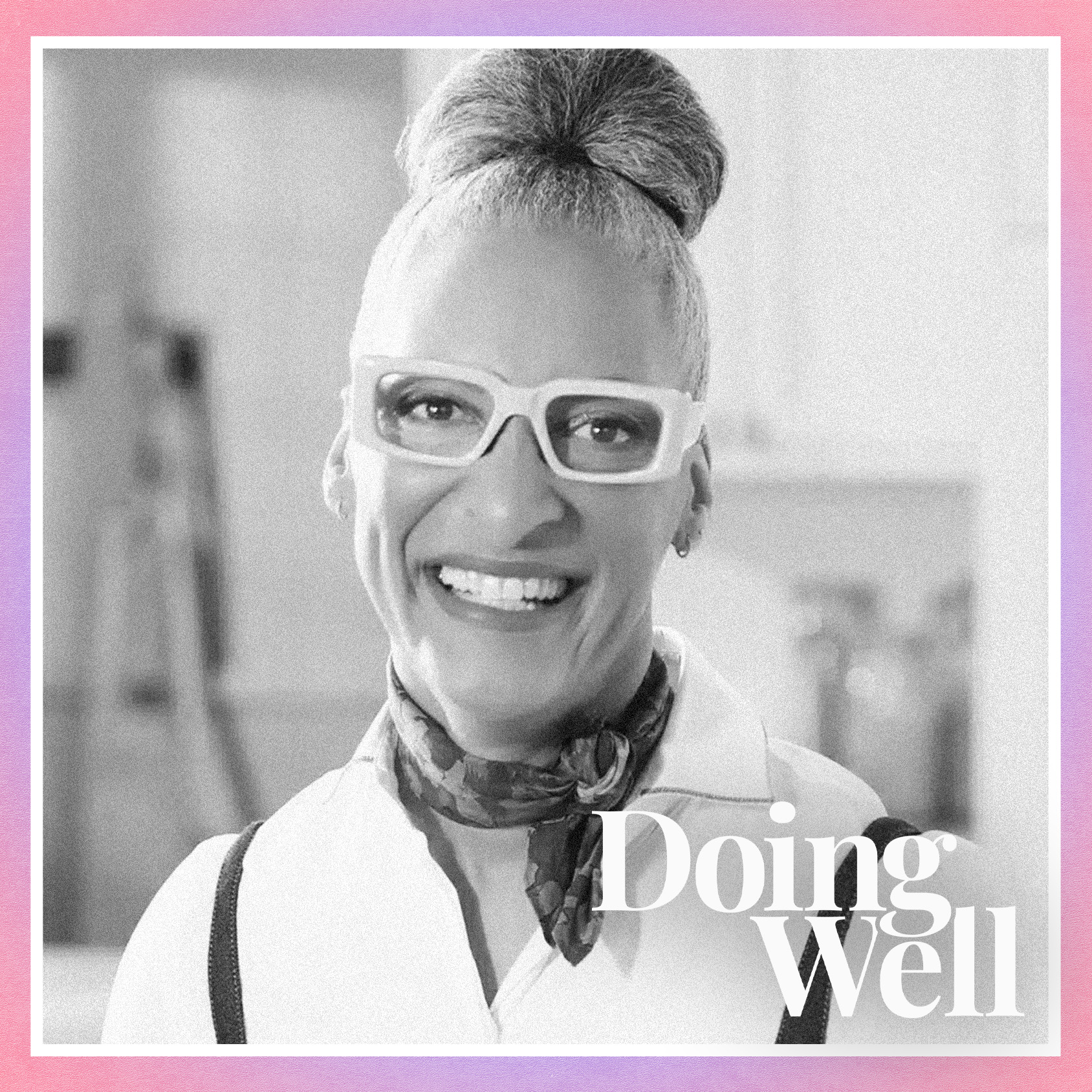

Why Celebrity Chef Carla Hall Rests When Astrology Tells Her To

"I have marked my calendar."

By Gabrielle Ulubay Published

-

The Best Under-$38 Wellness Buys I Could Find

Sponsor Content Created With CVS

By Emma Walsh Published

-

Kourtney Kardashian Says She "Pounded a Glass of Breast Milk" After Feeling Sick

Well, that's a choice.

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

Sarah Jessica Parker Shares the Way She Helps Her Twin Daughters Have a "Healthier Relationship" With Food

"My daughters will have the figures they have..."

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

Rebel Wilson Says She Received “More Attention for Weight Loss Than Any Movie” She’s Ever Done

“I know that’s superficial, but it was nice.”

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

There's a Huge Gap in Women's Healthcare Research—Perelel Wants to Change That

The vitamin company has pledged $10 million to help close the research gap, and they joined us at Power Play to talk about it.

By Nayiri Mampourian Published

-

Kourtney Kardashian Shares Candid Photo of Herself Breast Pumping

“That’s life.”

By Danielle Campoamor Published

-

15 Hair Growth Shampoos Experts Recommend for Serious Length

Rapunzel hair, coming right up.

By Marisa Petrarca Published

-

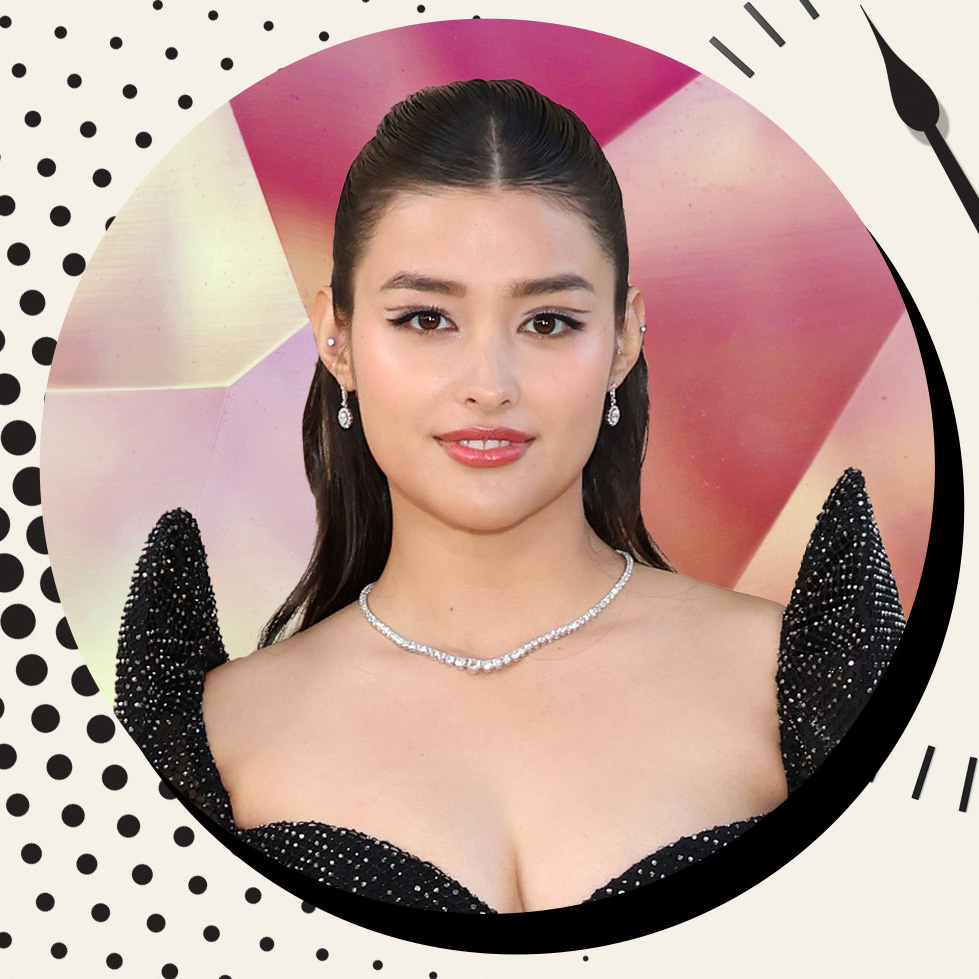

Misty Copeland Is Stepping Beyond Ballet

The professional ballerina talks nutrition, education, finding balance.

By Gabrielle Ulubay Published

-

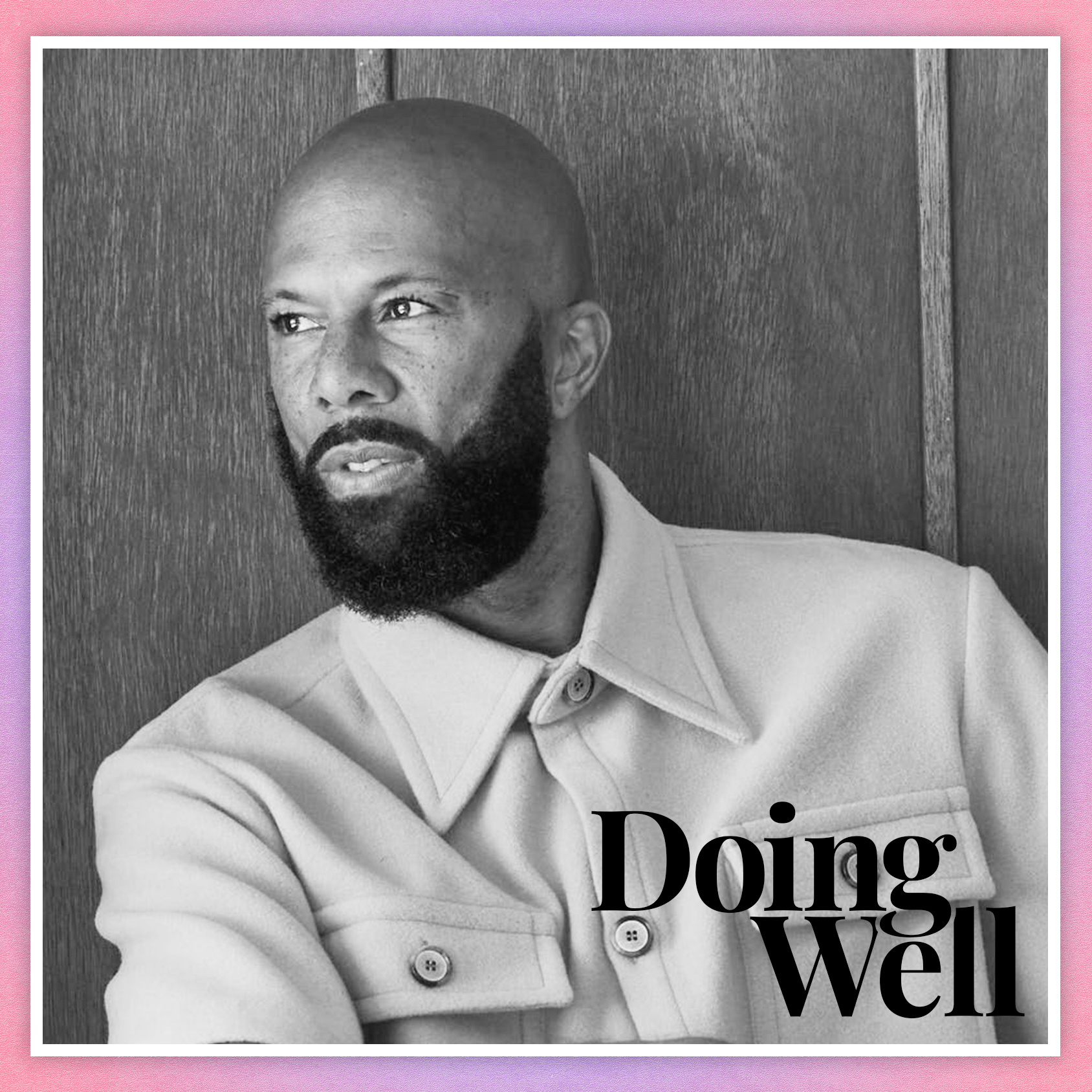

Common Doesn't Want Your Quinoa

"They're like, 'Yo, we got this quinoa,' and I don't like that."

By Gabrielle Ulubay Published

-

Keys Soulcare's New Facial Oil Is Perfect for Dry Winter Skin

Your new skin savior just dropped.

By Gabrielle Ulubay Published

-

The Secret to Model-Long Lashes Is a Great Eyelash Growth Serum

16 editor- and expert-reviewed picks for the best lashes of your life.

By Brooke Knappenberger Last updated

-

Would You Share Your DNA in Pursuit of Good Skin?

According to forward-thinking beauty biohacking brands, gene analysis is the future.

By Joane Amay Published

-

What It Means to Agatha Achindu to Be a "Wellness Architect"

Achindu recently published her cookbook, "Bountiful Cooking."

By Tanya Benedicto Klich Published

-

Heidi Klum Was Really "Upset" Over a False Report That She Was on a 900-Calorie-a-Day Diet

I'm with you, Heidi.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Kourtney Kardashian Barker’s New Beauty Gummy Vitamin Is Self-Care in a Bottle

The entrepreneur breaks down Lemme Glow after surviving a medical emergency.

By Deena Campbell Published