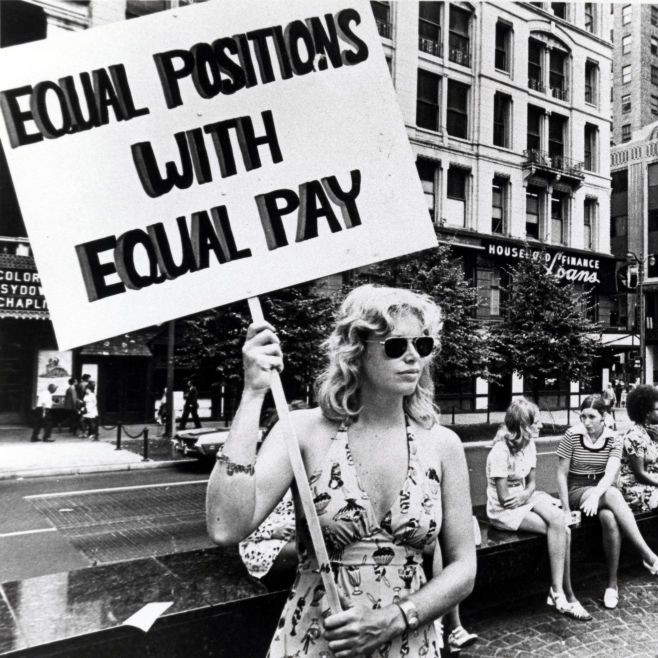

equal pay

Discover expert analysis and the modern take on Equal Pay, brought to you by Marie Claire.

-

The Change Makers: Constance Wu, Ava DuVernay, and Jessica Chastain

Inclusion. Representation. Diversity. Agency. Equality. On-screen and off-screen, these women are shaping the future of Hollywood.

By Allison Glock Last updated

-

Give Mom What She Really Wants This Year: Equal Pay

Moms have faced some of the biggest setbacks since the pandemic started. So this year, don’t just say it with flowers—say it with phone calls to your Senators and your HR department.

By Elizabeth Barajas-Román Published

-

It’s Time to End Equal Pay Days and Pass the Equal Rights Amendment

The passage of the ERA is a chance for our country to prove it truly values women.

By Hala Ayala Published

-

What Equal Pay Day Gets Wrong

The day marks how far into the year an average woman must work to earn what the average man earned the year prior. In her first finance column for Marie Claire, Sallie Krawcheck shares why Equal Pay Day also isn't measuring up.

By Sallie Krawcheck Published

-

Today, Black Women’s Equal Pay Day, Illustrates Just How Much Black Women Are Undervalued and Underpaid

In addition to the wage gap, new research from LeanIn.org shows that there are numerous "invisible" injustices as well.

By Megan DiTrolio Published

-

Latinas Make 54 Cents For Every Dollar a White Man Makes

It's 2019, people!

By Krystyna Chávez Published

-

Taylor Swift Talked Making Mistakes, Equal Pay, and Her Next Single in Her Teen Choice Awards Speech

"Please be kind to yourselves and stand up for yourself," she told her fans.

By Emily Dixon Published

-

No One In the World Is More Lit Than the U.S. Women's Soccer Team Right Now

When you win the World Cup, you party all week long.

By Ineye Komonibo Published

-

It's Tessa Thompson's Time to Shine

The actress, who stars in this month's 'Men in Black: International,' is the change she wants to see in Hollywood.

By Julia Felsenthal Published

-

Thandie Newton Will Be Paid the Same as Her Male Costars in 'Westworld' Season 3

Thandie Newton has confirmed that she'll earn the same pay as her male costars during season three of Westworld.

By Kayleigh Roberts Published

-

Hell Yeah: Jessica Chastain Helped Octavia Spencer Advocate for Equal Pay

Women helping women. 👏👏👏

By Rachel Epstein Published

-

"I Want to Learn to Fight Better": Emma Stone on Politics and Equal Pay

Our September cover star plays legendary tennis champ Billie Jean King in this month's Battle of the Sexes—here, she and costar Sarah Silverman explore how the role taught her to find her voice.

By Sarah Silverman Published

-

Rejoice: You'll Get 20 Percent Off at These Retailers on Equal Pay Day

I guess it's something?

By Megan Friedman Published

-

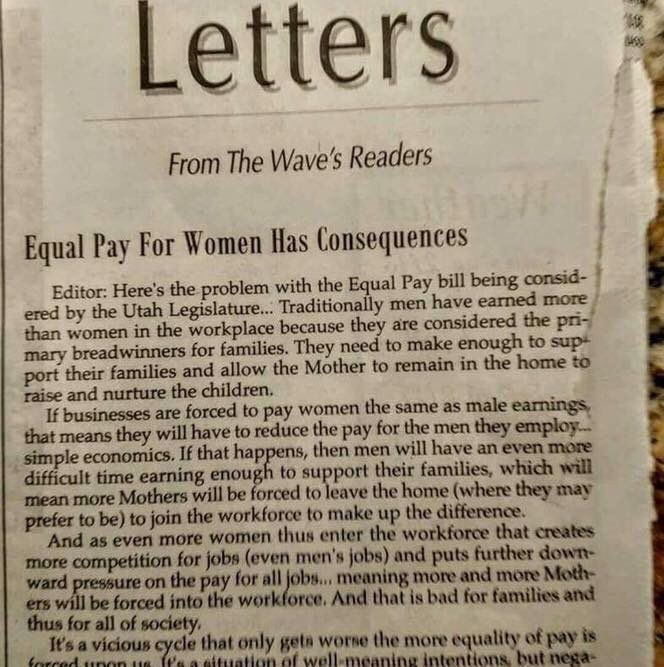

Justice Tastes So Sweet: This Republican Politician Resigned After Saying Equal Pay for Women Is Unfair to Men

But FYI he doesn't seem all that sorry for saying it.

By Marie Claire Published

-

Audi's Super Bowl Ad Calls for Equal Pay—And a Lot of People Aren't Happy About That

Seriously? In 2017?

By Megan Friedman Published

-

Venus Williams Is Preparing for the U.S. Open, But She's Not Done Speaking Out About Female Athletes and Equal Pay

In 2007, she led the charge for fair pay at Wimbledon. Now? "There's a lot more work to do."

By Samantha Leal Published

-

Worth the Fight: Inside the U.S. Women's Soccer Team's Important Boycott

"Gone are the days when women are going to say, 'We're just grateful to be here.'"

By Elise Craig Published

-

Just in Time for Equal Pay Day, There Is Now a National Monument Dedicated to Women's Equality

Woooo!

By Chelsea Peng Published

-

How the Caregiver Crisis Is Preventing Us from Fixing the Pay Gap

Women hold two-thirds of the jobs in the lowest paying fields—and it's keeping us down.

By Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka Published

-

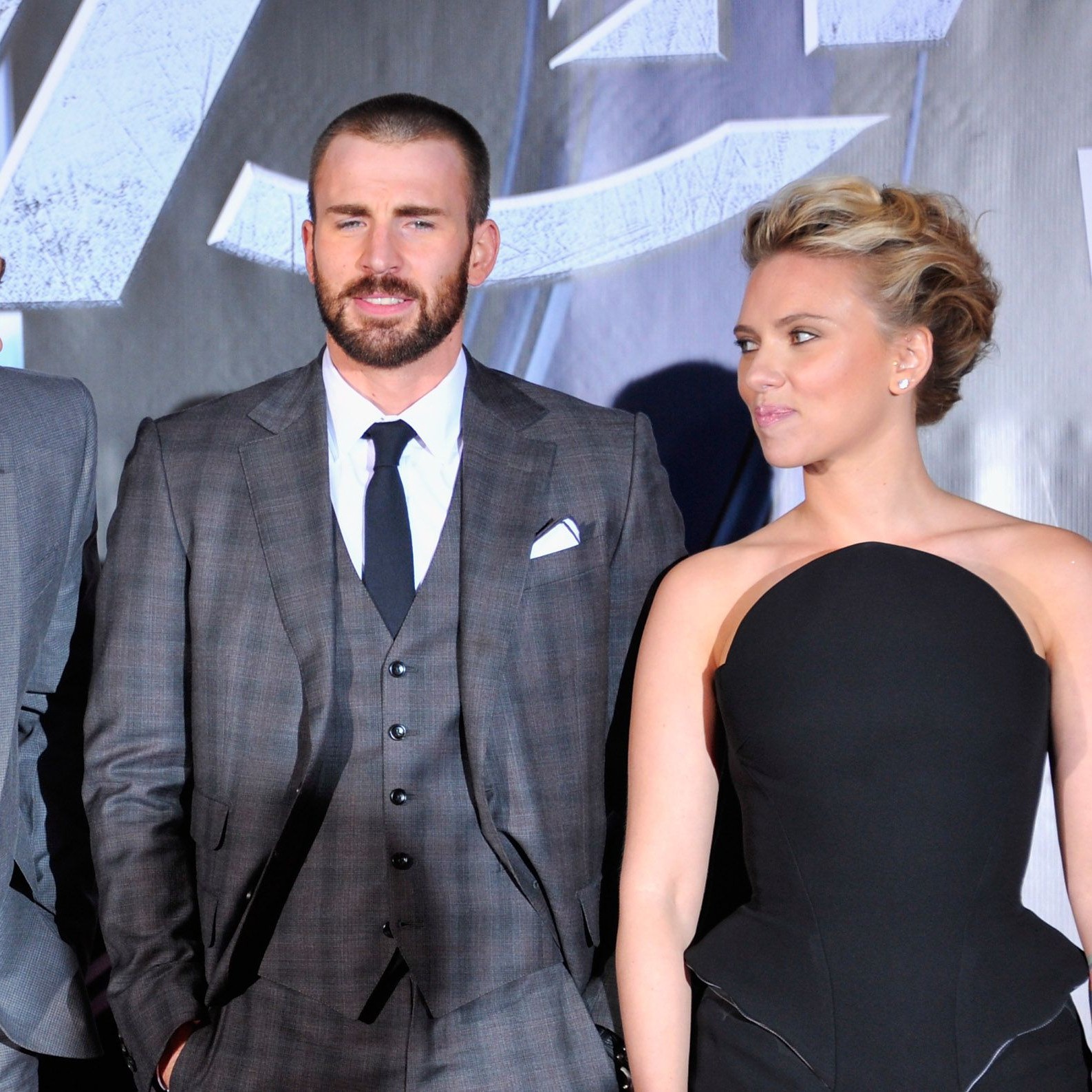

Take That Boys' Club: Scarlett Johansson Made as Much as Captain America and Thor in the 'Avengers' Movies

A win in the battle for equal pay.

By Megan Friedman Published

-

Please Stop Talking About Women Like We Only Vote with Our Vaginas

Just because we share an anatomy with Carly Fiorina doesn't mean we're automatic converts—especially in light of her anti-woman policies.

By Kayla Webley Adler Published

-

Why Female Doctors Are Paid So Much Less Than Their Male Counterparts

We're talking a difference of $15,000. (Yeah...)

By Megan Friedman Published

-

Pope Francis Says It's "Pure Scandal" That Women Don't Have Equal Pay

Preach! Literally!

By Megan Friedman Published

-

Here's Exactly How Much Less Money Women Make Than Men in 2015

Warning: the numbers are heartbreaking.

By Simedar Jackson Published

-

Sarah Silverman Made 83% Less Than Her Male Colleague, Is Fighting Back in the Best Way

And she wants you to do the same thing.

By Samantha Leal Published

-

Awesome Pro Wrestler Makes a Stand for Equal Pay

WWE's "divas" only get a fraction of the wages and screen time.

By Megan Friedman Published