Culture

Marie Claire’s pop culture obsessives offer their insight into the movies and TV shows you need to see, the books worth adding to your TBR stack, and catch up with the rising talent who should be on your radar.

-

The World’s Fastest Woman Didn’t Break the 4-Minute Mile. She Still Made History

In a superhero-worthy suit and under the global spotlight, Faith Kipyegon delivered a performance for the ages—pushing her limits and proving just how powerful women can be.

By Emily Abbate Published

-

My Radical Break-Up With Romantic Love

I stepped outside the relationship script—and it feels like I’ve unlocked a superpower.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

We're Keeping Track of the 'Love Island USA' Season 7 Cast, Including Who's Still Standing After Casa Amor

Here's what to know about all of the Islanders.

By Quinci LeGardye Last updated

-

Breaking Down the 'Squid Game' Ending, From the Surprising Winner to the Heartbreaking Deaths

You could say the conclusion of the Netflix phenomenon has left us shocked.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

'Love Island USA' Is Getting Messy—Here's How to Vote to Save Your Favorite Islanders in the Upcoming Eliminations

The next chaotic vote should be coming soon!

By Quinci LeGardye Last updated

-

Breaking Down All of the 'Squid Game' Season 3 Easter Eggs in the New Killer Arenas and Challenges

Production designer Chae Kyoung-sun shares her secrets behind the hit Netflix K-drama and how she teased the finale in her designs.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

36 Nostalgic, Sunny Movies That Just Feel Like Summer

Beat the heat by staying in and watching one of these classics.

By Nicole Briese Last updated

-

Meet 'The Ultimatum: Queer Love' Season 2 Cast—And Get to Know Who Is Giving and Receiving

We're sensing another dramatic installment of the Netflix reality hit.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

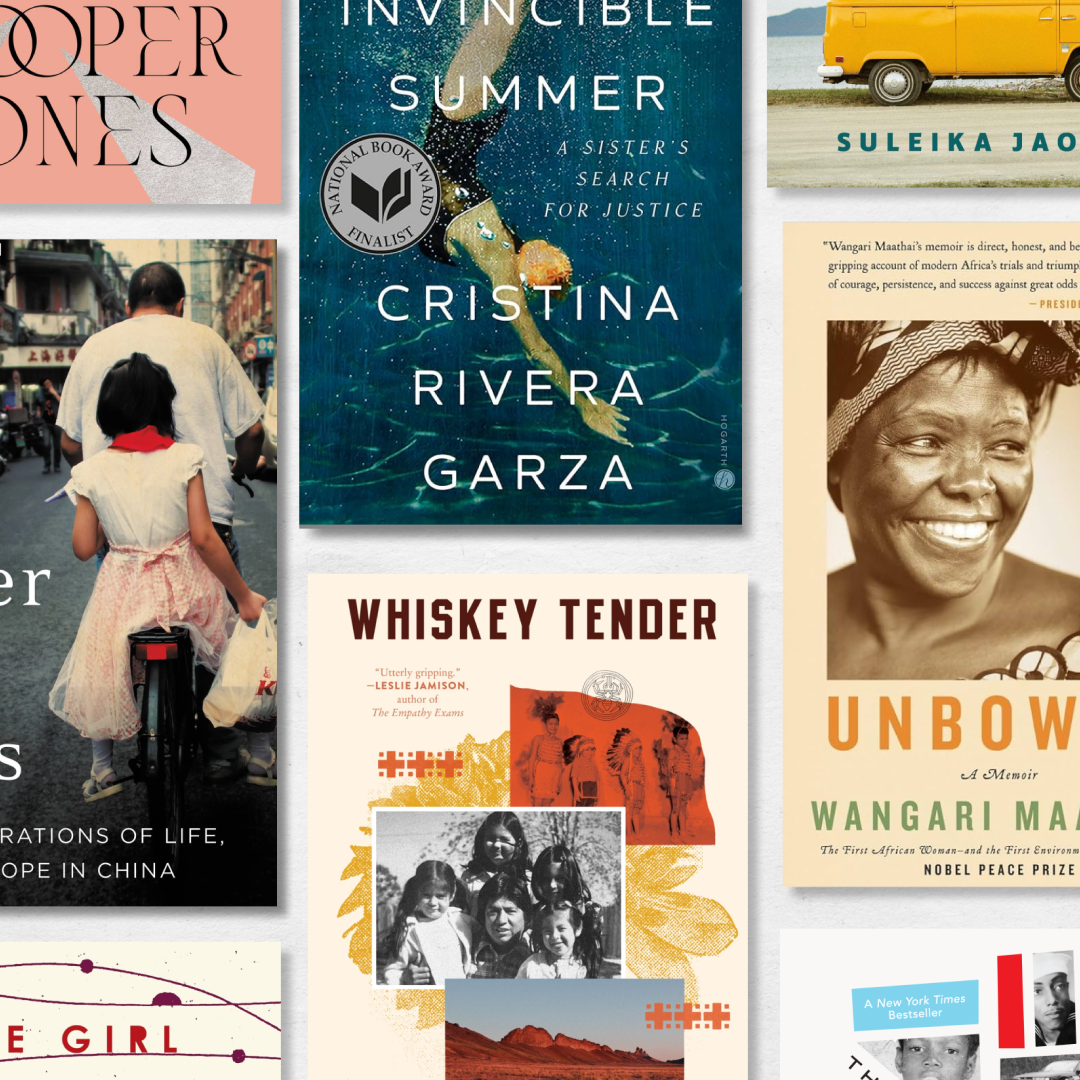

34 Fascinating Memoirs You Won't Be Able to Put Down

Make room on the nightstand.

By Alexis Jones Published

-

Did Olandria Carthen Leave 'Love Island?' Here's Why the People's Princess of Season 7 May Be Back

Fans have their fingers crossed that the Bama Barbie will return to the villa soon.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

We Got a Text! 'Love Island: Beyond the Villa' Will Premiere Next Month

Here's what we know about the 'Love Island USA' spinoff featuring PPG and all of your favorite season 6 islanders.

By Quinci LeGardye Last updated

-

'Perfect Match' Season 3 Will Return This Summer With Netflix Reality Reunions and Former Bachelor(ette)s

The hit series is coming back in August.

By Quinci LeGardye Last updated

-

Women Lead This Summer's Action Blockbusters—Here's What's Worth Seeing

We rounded up the best high-octane entertainment of the year so far, and what's coming soon.

By Sadie Bell Last updated

-

Allow the 18 Best Romance Movies of the Year So Far to Sweep You Off Your Feet

No summer fling? No problem.

By Quinci LeGardye Last updated

-

If You're in the Mood for a Great Romance, Nothing Compares to These Korean Movies

They'll shatter your heart, then put it back together again.

By Marina Liao Last updated

-

'Love Island USA' Is Implementing Brand-New Rules to Casa Amor—Here's What to Know

It's about to be a game-changing week for the Islanders and Bombshells.

By Quinci LeGardye Last updated

-

'KPop Demon Hunters' Is Voiced by Real-Life Hitmakers. Meet the Cast of Netflix's Animated Sensation

HUNTR/X is about to be your new favorite fictional band.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

'The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives' Is Getting a Reunion After That Bombshell Finale—But Not All of #MomTok Will Be Back

Here's everything we know about the upcoming special.

By Quinci LeGardye Last updated

-

Get Ready to Return to Your Favorite Small-Town: 'Virgin River' Season 7 Officially Wrapped Filming

Jack and Mel may have tied the knot, but there's still more melodrama (and romance!) to come from the Netflix hit.

By Radhika Menon Last updated

-

After That Explosive Finale, Will 'We Were Liars' Return for Season 2? Fans of the Book Series Think So

It seems like we could be returning to Beachwood for another mystery.

By Quinci LeGardye Published

-

We Scoured the Archives and Rounded Up the 70 Best 2000s Movies of All Time

We recommend you get cozy in your Juicy Couture tracksuit and tune in.

By Brooke Knappenberger Last updated

-

Netflix's Crime Drama 'The Waterfront' Is Based on a True Story—Inspired by the Creator's Own Family

The Buckleys may be fictional, but there's truth to their fishing and drug-smuggling empire.

By Radhika Menon Published

-

'Nobody Wants This' Season 2 Will Premiere This Fall for More Hot Rabbi Romance

Here's what we know about the next installment of the hit rom-com series.

By Quinci LeGardye Last updated

-

Why "Let's Get Dressed" Podcast Host Liv Perez Advocates for a Non-Linear Career

The content creator speaks to editor-in-chief Nikki Ogunnaike for the 'Marie Claire' podcast "Nice Talk."

By Lia Beck Published

-

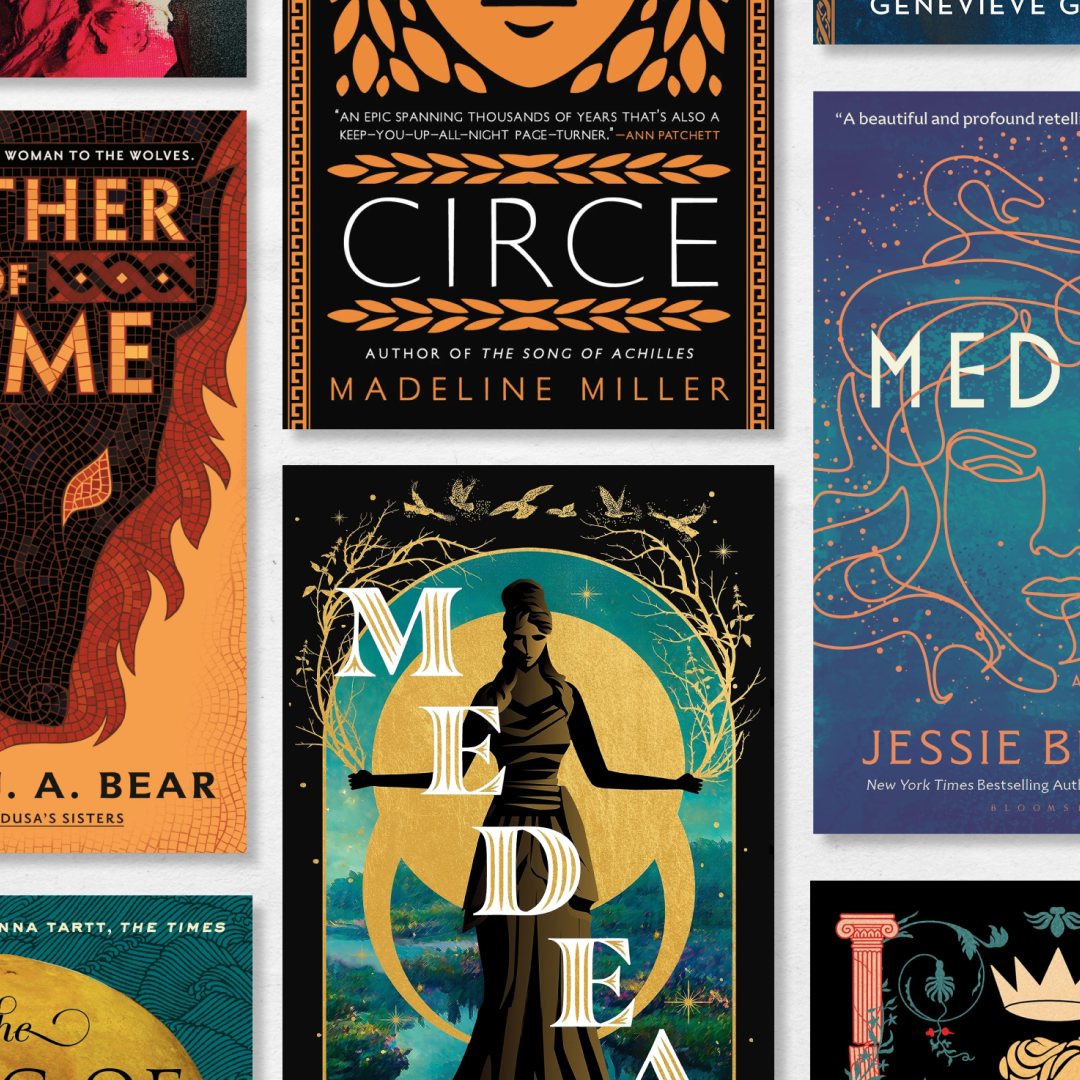

16 Books That Put a Modern Day Twist on Ancient Mythology

All the gods and goddesses you know and love, but with a scandalous or feminist twist.

By Nicole Briese Published

-

Meet the Cast of 'The Waterfront,' Netflix's Latest Small-Town Crime Drama and Your Next Binge-Watch

Get acquainted with the morally ambiguous Buckley family.

By Radhika Menon Published