Where Are All the Women Designers?

There's something missing from luxury fashion houses. And it's too obvious to be an oversight.

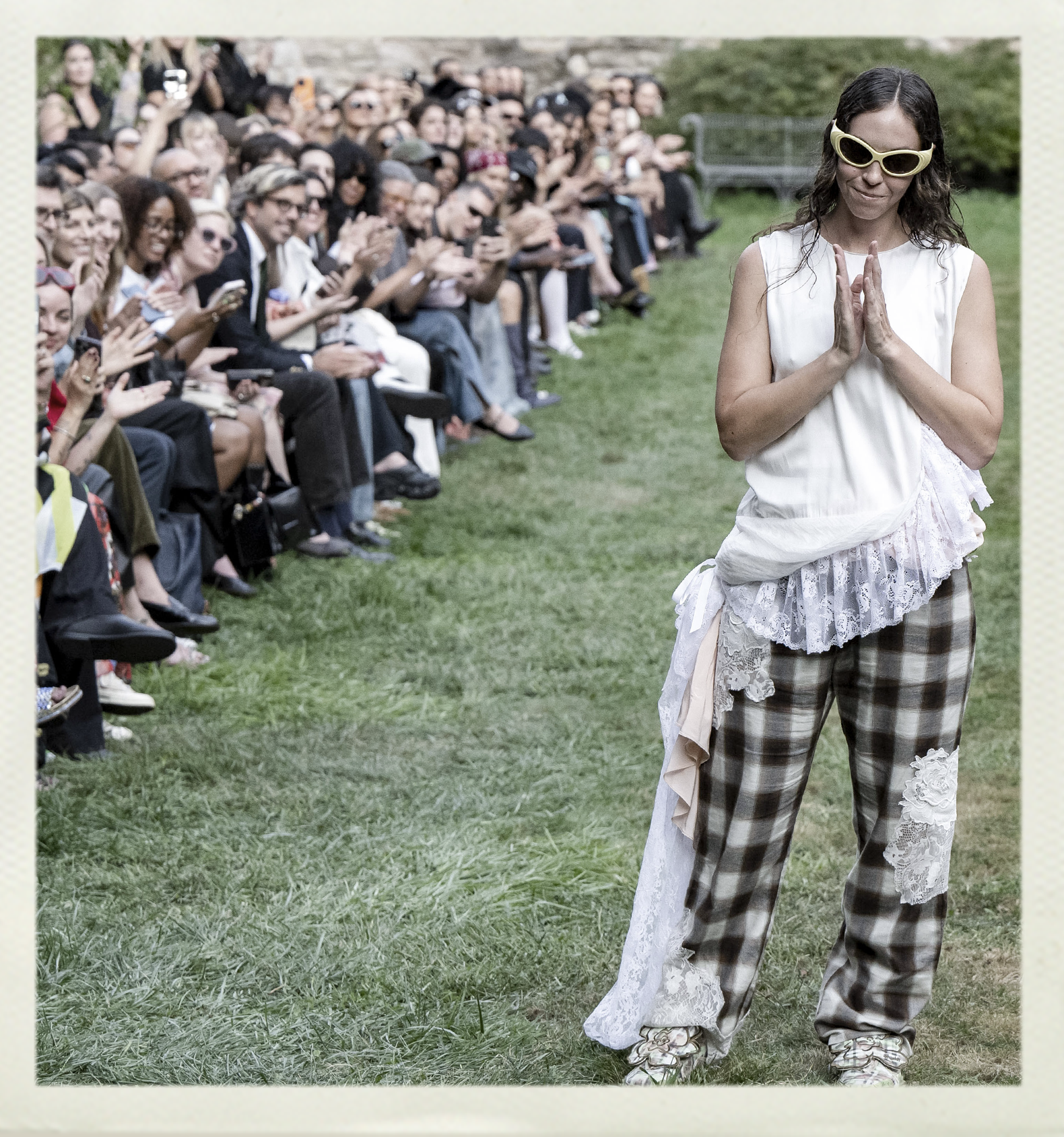

Five years ago, Hillary Taymour, the founder of one of New York City’s buzziest independent fashion labels, Collina Strada, was interviewing for a new job. A creative director post had opened at a European women’s luxury brand—and if Taymour landed the role, she’d level up from dressing a devoted, US-based clientele to designing for millions of women worldwide. After eight months spent interviewing with HR reps and company executives, the SCAD alum felt confident she’d landed the gig. She even began packing her bags, arranged for someone to take over her Manhattan lease, and planned her first-day outfit as the new leader of a heritage fashion house.

But then the brand called back with a disheartening update. A male designer was selected instead. Taymour was heartbroken, but not surprised. To date, she’s been in the running for creative director openings at seven other women’s luxury brands. All but one position went to a male designer; an exception she says was simply a company mandate. “The lack of women being given the opportunity to dress women is appalling,” Taymour says, resigned, on a Zoom call in June.

Her story crystallizes a broader issue at the top of the fashion food chain: coveted luxury womenswear creative director roles—those who design runway collections and set trends that eventually filter down to fast fashion—are still overwhelmingly held by men. Despite luxury fashion being an industry built around what women want to wear, women are rarely given a say in what that actually is.

Over the last few years, the major luxury houses have been playing a game of “creative director musical chairs,” as the fashion commentariat has come to call it. Alessandro Michele left Gucci and is now at Valentino; Pierpaolo Piccioli, previously at Valentino, starts at Balenciaga this October. Demna Gvasalia, formerly of Balenciaga, has taken over at Gucci, following a two-year tenure by Sabato De Sarno, who took over from Michele.

The turnover tumult has been entertaining, sure, but deeply disappointing in terms of gender diversity. Two legacy women creative directors, Maria Grazia Chiuri for Dior and Virginie Viard at Chanel, were benched and replaced by Jonathan Anderson (Dior) and Mathieu Blazy (Chanel). A few female designers have recently risen through the ranks—Rachel Scott took on Proenza Schouler’s top slot, and Meryll Rogge was appointed at Marni—but even still, the disparity is stark; Currently, only ten of 33 creative director roles at fashion houses designing for women are held by women, and only two are women of color. Statistically speaking, women shaping luxury from the top down are as rare in 2025 as they were in Gabrielle Bonheur “Coco” Chanel’s 1910s heyday.

Being a woman isn't a job requirement to design for women, of course. Countless talented male artists throughout history and at present make phenomenal, well-fitting, and fully realized womenswear. But the lack of women behind the runways suggests a deeper issue.

Candidates are certainly qualified. Female designers like Grace Wales Bonner, Martine Rose, Simone Rocha, and numerous others frequently earn six-figure grants and awards from the CFDA Fashion Fund and the LVMH Prize, both of which are akin to 24-karat résumé gold stars. These women are also the brains behind highly lucrative, massively viral items: Bonner’s take on the Adidas Samba continues to sell out at every drop. Whenever Taymour interviews at a fashion house, executives rave about her brand’s sales doubling year-over-year sales since its launch in 2009.

Get exclusive access to fashion and beauty trends, hot-off-the-press celebrity news, and more.

But the same obstacle continues to arise: women working within corporate structures are often praised but seldom promoted. A 2024 Women in the Workplace report from McKinsey discovered that women are significantly less likely to see upward career growth regardless of their performance, and this “broken rung in the corporate ladder” keeps their careers at a standstill.

Mimma Viglezio, a former executive vice president for global communications at Gucci Group, says the inherent male culture of luxury fashion’s C-Suites makes it difficult for decisions to go in a woman’s favor. “There's nobody in the boardroom saying, ‘We don't want women,’ or that women aren’t good enough. But male executives see a woman at the head of a brand as a risk,” she explains. Years ago, a luxury jeweler’s CEO told her bluntly, “The problem with hiring young women? You get pregnant, take a year off, and I still have to pay you.”

Disturbingly, Viglezio's experience in the early aughts mirrors Taymour's from today: “To even be considered for these creative director jobs, I have to go into these meetings and say, ‘Hi, I'm a woman. I'm willing to move, and I'm not planning on having children.' At this point, I think I need to show them an X-ray of my hysterectomy," says the designer.

Designer Hillary Taymour taking a bow after Collina Strada's SS25 runway show.

It’s counterintuitive that companies resist putting women in charge—even as it undercuts their own bottom lines. The global women’s apparel market is projected to hit $1 trillion in 2027, while men’s will come closer to $639.12 billion, according to UniformMarket, a statistics-led e-commerce platform. And as recent history shows, women are incentivized to put their 80 percent of total consumer spending power toward brands where they see themselves reflected. Under Chiuri’s leadership at Dior, female empowerment became a guiding principle—whether through a sculpted hourglass skirt suit or an unmissable “We should all be feminists” slogan tee—and brand sales jumped from €2.7 billion in 2018 to more than €9 billion by 2023, per HSBC estimates. Meanwhile, luxury sourcing expert Gab Waller began receiving Chloé requests for the first time in her seven-year career after Chemena Kamali’s Fall 2024 debut of sensual, unfussy blush chiffon and lace silhouettes.

We’ve seen that when a female creative director has her own distinct, influential style, she becomes the ultimate consumer archetype and brand ambassador. Take The Row, which reached a $1 billion valuation in 2024 by selling functional, freaky footwear and modern bohemian basics like easy maxi dresses and big, beat-up totes. Their creators? Two impeccably dressed sisters at the helm with a nearly all-women team beside them. “When you buy into that brand, you are buying into the idea that you might possess an iota of the insouciant, cool style that Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen have,” says Mosha Lundström Halbert, fashion and culture journalist and founder of NEWSFASH.

Waller adds that anything once touched by designer Phoebe Philo—a woman who makes offbeat elegance look as effortless as breathing—is regarded as holy by her clients. “I still get requests for particular styles from her Celine era (Philo served as creative director from 2008 to 2017), and her shoes are our best-selling, most-requested category,” she says. “I’m receiving a lot of requests across the U.S., the Middle East, and the U.K. for a burgundy sandal from Philo’s solo line—I rarely see items with that level of global pull.”

That isn’t an accident: Quite literally, female designers understand what it’s like to walk in their customers’ footsteps. They sympathize with the frustration of trying to put an iPhone into a too-small pants pocket or finagling with an open-back blouse that doesn’t allow for a bra. They know an oversized jacket is a godsend on 12-hour days out of the house, because it has room for an extra layer underneath. “The design touches female designers often use are like little winks—I see you, and I understand your life and your body,” Lundström Halbert adds. “They’re not added bonuses—just aspects of good design.”

Which is why some firebrand female designers have carved out their own spaces rather than wait for gatekeepers to make room, to lucrative effect. Six years after Phoebe Philo left Celine, her namesake direct-to-consumer collections so frequently sold out that she expanded to luxury department stores. The multi-billion-dollar girlhood aesthetic is rooted in Simone Rocha and Sandy Liang’s independent runways, which both began with pop-up stores and Substack shout-outs from devoted fans. The It bag Hall of Fame of today contains as many pieces from The Row as it does Louis Vuitton or Gucci—even though it doesn’t belong to a major conglomerate. All proving that corporate luxury’s support is a legitimacy boost in the eyes of the industry—not a definitional requirement for success.

Still, it would be nice to have it. At the time of our interview, Taymour was in the running for another creative director gig at a women’s luxury brand. A month later, the designer heard she hadn’t gotten the role, but a female peer had. It was another disappointment—but at least, this time, with a silver lining.

This story appears in the 2025 Changemakers Issue of Marie Claire.

Emma Childs is the fashion features editor at Marie Claire, where she explores the intersection of style, culture, and human interest storytelling. She covers zeitgeist-y style moments—like TikTok's "Olsen Tuck" and Substack's "Shirt Sandwiches"—and has written hundreds of runway-researched trend reports. Above all, Emma enjoys connecting with real people about style, from designers, athlete stylists, politicians, and C-suite executives.

Emma previously wrote for The Zoe Report, Editorialist, Elite Daily, and Bustle, and she studied Fashion Studies and New Media at Fordham University Lincoln Center. When Emma isn't writing about niche fashion discourse on the internet, you'll find her shopping designer vintage, doing hot yoga, and befriending bodega cats.