relationships

Discover expert analysis and the modern take on relationships, brought to you by Marie Claire.

-

Monica Barbaro and Andrew Garfield Match at Wimbledon

The couple's coordinated outfits were a nod to the tennis tournament's all-white dress code.

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Travis Kelce Not Proposing to Taylor Swift Anytime Soon

"Taylor has had quite the year," a source explained.

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Archie and Lilibet Have a "Sweet" July 4 Tradition

The little royals have embraced their mom and dad's unique love story.

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

William "Inherited" King Charles's "Fear of Commitment"

Kate allegedly "made a pact" after learning about William's "inherent fear of tomorrow."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Swifties Think Matty Healy Just Referenced Taylor Swift

"And I just wanted to remind you...I bleed for you."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Queen Elizabeth Told Friends Kate Middleton Was a "Problem"

The late monarch allegedly had "no idea what Kate actually does."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Taylor Swift Pairs a Corset Top With a Miu Miu Mini Skirt

Taylor Swift loves corset tops as much as she loves Travis Kelce (probably).

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Kate and William's "Mental Challenge" at Home

The Prince and Princess of Wales's home life sounds far from tranquil.

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

A "Major Shift" Is Coming for William and Kate

"For her, less is actually more," a royal biographer explained.

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Prince William Will "Feel the Void" at Royal Ascot

"William holding the fort on his own isn't unusual."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Diana and Sarah Were "Outsiders" in Royal Family

"Something happened in their personal lives which they found was impossible to hurdle."

By Amy Mackelden Published

-

Ariana Grande Reportedly Hung Out With Rumored Boyfriend Ethan Slater's Wife Lilly Jay at Their House

There's a LOT we don't know.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Keep The Spark Going With These Non-Cliché Second Date Ideas

You can do better than dinner and a movie.

By The Editors Last updated

-

I'm a Travel Writer—These Are the Best Health Spa Resorts in the U.S.

It’s pampering time.

By Michelle Stansbury Published

-

A Great Date Doesn't Have to Be Expensive—These Date Ideas Are Fun *And* Affordable

"Love don't cost a thing." —J.Lo

By The Editors Last updated

-

Harry Styles Made Out With His Celebrity Crush Emily Ratajkowski in Tokyo

Life works in mysterious ways sometimes.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Selena Gomez and Zayn Malik Sparked Dating Rumors, and Gigi Hadid "Has No Problem" With It

A happy ending for all??????

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

Are Phoebe Dynevor and Andrew Garfield Dating? They Reportedly "Clicked" at the GQ Awards

Cute!

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

The All-Time Best Celebrity Couple Halloween Costumes

Honestly, we're impressed.

By Charlotte Chilton Published

-

King Charles III and Queen Consort Camilla's Relationship: A Timeline

With the passing of Queen Elizabeth II, Charles has ascended to the throne as king.

By The Editors Published

-

Megan Fox Texted Her Stylist That She "Cut a Hole" in Her Outfit to "Have Sex" With Machine Gun Kelly

Girlie, what?

By Iris Goldsztajn Published

-

30 Female-Friendly Porn Websites for Any Mood

Features All the best websites, right this way.

By Kayleigh Roberts Published

Features -

The 13 Best Virtual Date Night Ideas

Whether you're on your first date with them or your hundredth.

By Bianca Rodriguez Published

-

The 20 Best Winter Date Outfits, Cold Be Damned

Buying Guide Your guide for when it's cold out, but you have a hot date.

By Julia Marzovilla Published

Buying Guide -

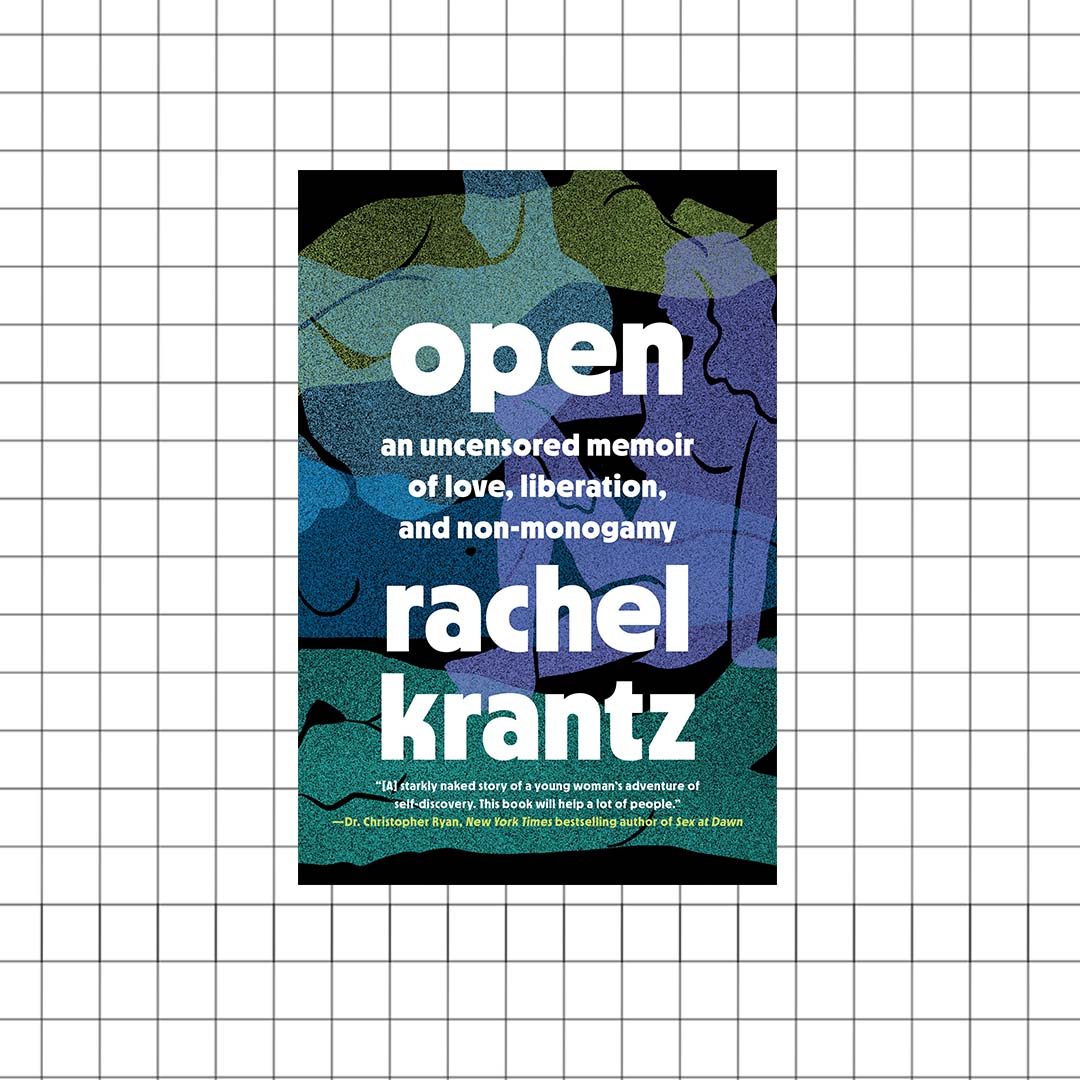

Diary of a Non-Monogamist

Rachel Krantz, author of the new book 'Open,' shares the ups and downs of her journey into the world of open relationships.

By Abigail Pesta Published

-

Megan Fox and Machine Gun Kelly's Love Will "Be Around for a Long Time," Body Language Expert Predicts

They've been through a lot.

By Iris Goldsztajn Published